Explore the splendor and melancholy of Edo Yoshiwara culture through freely downloadable ukiyo-e prints that capture the unique aesthetic world of Japan’s most famous pleasure district, offering valuable visual references for designers and illustrators.

The Birth and Flourishing of Edo Yoshiwara Culture

The Establishment of Yoshiwara – A “Special Domain”

Located in what is now the Senzoku area of Tokyo’s Taito Ward, Yoshiwara was officially established in 1617 with the permission of the Tokugawa shogunate. The policy of consolidating previously scattered brothels into a single location originated from Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s directive that “courtesans should be gathered in one place.” Following Shinmachi in Osaka and Shimabara in Kyoto, Yoshiwara became Edo’s designated pleasure quarter.

Enclosed within an expansive area of approximately 100,000 square meters, Yoshiwara existed as a unique space known as “kugai” (public realm). Once through its great gate, visitors entered a separate world detached from the strict class hierarchies of Edo society. Even samurai had to surrender their swords, putting them on equal footing with commoners when interacting with courtesans—an extremely rare phenomenon in feudal Japan.

For Western readers unfamiliar with Edo Japan’s social structure, it’s worth noting that the Tokugawa shogunate maintained a rigid four-class hierarchy (samurai, farmers, artisans, and merchants). The existence of spaces like Yoshiwara where these strict social boundaries temporarily dissolved was revolutionary in a society where one’s social position determined nearly every aspect of life.

Yoshiwara as a Hierarchical Society

A distinctive feature of Edo Yoshiwara culture was its strict internal hierarchy. Courtesans were categorized into multiple ranks, starting from the highest “tayū,” followed by “kakoi” (enclosed), “kamiko” (paper-robed), and “sancha-jorō” (tea-house women). The tayū, in particular, were not merely sexual companions but cultured individuals versed in poetry, koto (Japanese zither), tea ceremony, and kōdō (incense appreciation), and interacting with them required following a complex set of protocols known as “tayū-dō” (the way of the tayū).

Engaging with a tayū did not necessarily involve physical relations; enjoying refined conversation and cultural exchange was also an essential aspect of “play.” Consequently, meeting a tayū required enormous expenses—equivalent to over 500,000 yen ($3,500) for a single night by contemporary standards, sometimes exceeding one million yen ($7,000). For ordinary citizens, they were figures one might meet once in a lifetime, if at all.

Edo Yoshiwara Culture and Ukiyo-e – Documentation and Admiration

Yoshiwara as a Fashion Trendsetter

The courtesans of Yoshiwara, especially the high-ranking oiran and tayū, served as trendsetters in Edo. Their hairstyles, kimono patterns, and makeup techniques became objects of admiration and imitation among town girls. Songs and dances that became popular in Yoshiwara quickly spread throughout Edo.

This cultural influence of Yoshiwara was amplified through its connection with ukiyo-e, a new art form that emerged during this period. Artists like Suzuki Harunobu, Kitagawa Utamaro, Katsushika Hokusai, and Utagawa Hiroshige created numerous works depicting Yoshiwara. Their portrayals of courtesans were not merely sexual objectifications but expressions of “beauty” infused with a certain respect and admiration.

Ukiyo-e, literally “pictures of the floating world,” was a genre of woodblock prints and paintings that depicted the transient, hedonistic culture of Japan’s urban centers during the Edo period (1603-1867). These artworks served not only as entertainment but also as advertisements, celebrity portraits, and documentation of cultural phenomena.

Value as Genre Paintings

Ukiyo-e depicting Yoshiwara also hold value as genre paintings. They meticulously document interior decorations, furnishings, clothing, hairstyles, and other aspects of Edo’s living culture. Scenes of courtesans’ rooms, customer interactions, and ceremonial processions like the “oiran dōchū” (courtesans’ parade) provide precious visual records of Edo Yoshiwara culture.

These images detail kimono patterns, hairstyles, makeup techniques, and mannerisms that varied according to rank and status. They serve as indispensable visual references for contemporary designers and illustrators seeking to recreate the aesthetics of the Edo period.

Seasons and Events in Yoshiwara – Staging the Extraordinary

Seasonal Aesthetics

One of the charms of Edo Yoshiwara culture was its elaborate seasonal celebrations. Spring brought cherry blossoms, summer featured fireflies and cooling festivities, autumn showcased moon-viewing and maple leaves, and winter offered sake drinking in snow-covered settings. Each season was presented with meticulous attention to enhancing its distinctive atmosphere.

Particularly noteworthy was the “temporary planting” of cherry trees only in March—a luxurious presentation unique to Yoshiwara. Planting cherry trees that weren’t naturally rooted in the area just for their peak blooming period symbolized how Yoshiwara itself represented a kind of artificial construct or fantasy space.

Annual Events in Yoshiwara

Yoshiwara’s representative events included the New Year’s “kadomatsu” (gate pine) decorations, March’s “cherry blossom banquet,” July’s “boat excursions,” August’s “summer cooling,” October’s “autumn leaves banquet,” and December’s “soot cleaning.” These were not merely seasonal celebrations but cultural practices unique to Yoshiwara, accompanied by distinctive rituals and customs.

Other characteristic spectacles included “Yoshiwara niwaka” (impromptu performances) and “keshō-mawashi” (processions of courtesans moving to new establishments). These scenes were also favorite subjects for ukiyo-e artists, appearing in numerous works.

Aesthetics and Expressive Techniques in Yoshiwara Ukiyo-e

Idealized Beauty

Courtesans depicted in ukiyo-e were often presented in idealized forms. Slender faces with refined features, luminously white skin, and graceful fingers were the beauty standards of the time, and artists portrayed these qualities in highly sophisticated ways.

Kitagawa Utamaro’s bijin-ga (pictures of beautiful women) exemplify this approach. Utamaro achieved psychological depth beyond mere beauty portraits by expressing subtle emotional nuances in the expressions and gestures of courtesans. Such delicate expressions symbolize the aesthetics of Edo Yoshiwara culture.

Symbolism in the Background

Ukiyo-e depicting Yoshiwara often incorporated symbolic meanings and wordplay. For example, a courtesan applying makeup before a mirror symbolized “utsushi-mi” (the ephemeral nature of life), plum blossoms represented integrity and refinement, and willows signified flexibility and strength.

Additionally, the paintings on hanging scrolls and folding screens, and objects held by courtesans were often arranged with specific meanings. Deciphering these allegories adds depth to the appreciation of ukiyo-e.

Contemporary Value of Yoshiwara Ukiyo-e – Potential as Design Sources

Composition and Design Elements

Ukiyo-e depicting Edo Yoshiwara culture contain numerous elements applicable to modern graphic design. Bold compositions, effective use of negative space, color contrasts, and expressive line work offer much for contemporary designers to learn from.

Particularly noteworthy are the color schemes that achieve rich expression with limited colors and complex pattern designs. The stylized depictions of geometric patterns and natural motifs found in kimono patterns and interior decorations remain applicable to contemporary pattern design.

A Treasury of Cultural Context

The visual expressions of Edo Yoshiwara culture in ukiyo-e embody uniquely Japanese aesthetic sensibilities and cultural contexts. They offer insights into distinctive Edo aesthetic concepts like “iki” (stylish sophistication) and “sui” (refined taste), sensitivity to transience connecting to “mono no aware” (the pathos of things), and expressive techniques emphasizing “yojō” (lingering emotion).

Understanding these cultural contexts allows for a deeper incorporation of traditional Japanese aesthetics into modern design, beyond merely borrowing forms and colors.

The Duality of Yoshiwara and its Courtesans – Behind the Glamour

The Reality of Courtesans’ Lives

While celebrating the glamorous aspects of Edo Yoshiwara culture, we must not forget that its economic foundation rested on the commodification of women, many of whom were sold into the profession due to poverty or family debts.

Though the system of “mikudashi” (redemption) offered the possibility of freedom, in reality, most courtesans spent their entire lives within the pleasure quarter due to exorbitant debts and interest. Behind the splendid images portrayed in ukiyo-e lay this harsh reality.

Yoshiwara in Literature

Literary works from the Edo period also depict the lives and emotions of Yoshiwara courtesans. Works like Ihara Saikaku’s “The Life of an Amorous Man” and “Five Women Who Loved Love,” and Chikamatsu Monzaemon’s “The Love Suicides at Sonezaki” vividly portray the inner workings of pleasure quarters and the sufferings of courtesans.

Genres like ukiyo-zōshi (books of the floating world), ninjōbon (books of human feelings), and sharebon (witty books) provide detailed descriptions of Yoshiwara customs and culture, serving as valuable resources alongside ukiyo-e for understanding Edo Yoshiwara culture

Artists Who Depicted Yoshiwara – Their Lineage and Characteristics

Hishikawa Moronobu and Early Ukiyo-e

Hishikawa Moronobu (c. 1618-1694), who was active in early Edo, is considered the founding father of ukiyo-e. Moronobu vividly depicted the Yoshiwara of his time in works like “Yoshiwara Koi no Michishirube” (A Guide to Love in Yoshiwara). His genre paintings are characterized by their realism and beautiful line work, establishing the foundations for later ukiyo-e.

Official Regulations and Shunga

Among pictures depicting Yoshiwara, many were “shunga” (spring pictures) portraying sexual intercourse. Though shunga were subject to shogunate regulations throughout the Edo period, many works were nevertheless produced and circulated secretly. The shunga of artists like Suzuki Harunobu, Kitagawa Utamaro, and Katsushika Hokusai are valued not merely as sexual depictions but as works of high artistic merit.

For Western readers, it’s important to note that unlike in contemporary Western societies where erotic art was often marginalized, in Edo Japan, shunga was created by the same mainstream artists who produced other ukiyo-e genres and was collected by people from all social classes, including women.

Tsutaya Jūzaburō and Ukiyo-e Publishing

Publisher Tsutaya Jūzaburō (1750-1797) made significant contributions to the spread of Edo Yoshiwara culture. He discovered talented artists like Kitagawa Utamaro and Tōshūsai Sharaku, producing refined ukiyo-e prints. Focusing particularly on publishing bijin-ga depicting Yoshiwara courtesans, these prints were widely appreciated by ordinary Edo citizens.

Freely Downloadable Ukiyo-e Resources Depicting Edo Yoshiwara Culture

Finally, I’ll introduce high-quality ukiyo-e resources depicting Edo Yoshiwara culture that contemporary designers and illustrators can reference. All are freely downloadable and offer valuable material for creative activities.

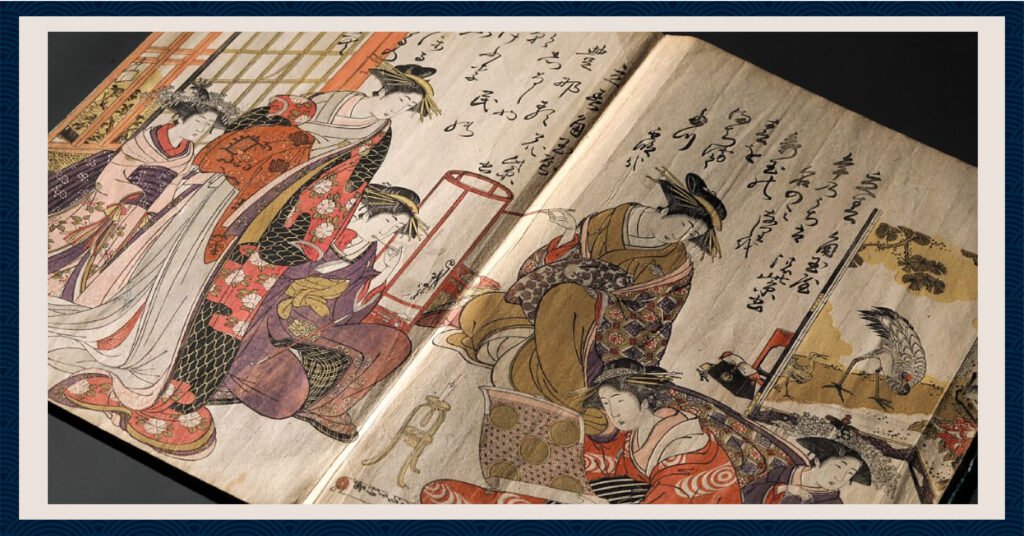

1. Library of Congress Collection: “Seirō Bijin Awase”

This valuable resource offers “Seirō Bijin Awase” (Beauties of Yoshiwara), one of the finest multicolored woodblock printed books in Japan. Published in 1770, the book depicts 166 courtesans of Yoshiwara, with their names and affiliated brothels, each illustration accompanied by a haiku in the background.

The work consists of five chapters compiled according to haiku themes: volume 1 for cherry blossoms, volume 2 for little cuckoos, volume 3 for the moon, volume 4 for autumn leaves, and volume 5 for snow. Though not directly credited, Suzuki Harunobu (c. 1725-1770) is mentioned in the preface and believed to have designed the illustrations. Harunobu was a leading ukiyo-e artist of the Meiwa era (1764-1771), renowned for his skill in depicting beautiful women and pioneering nishiki-e (multicolored woodblock prints).

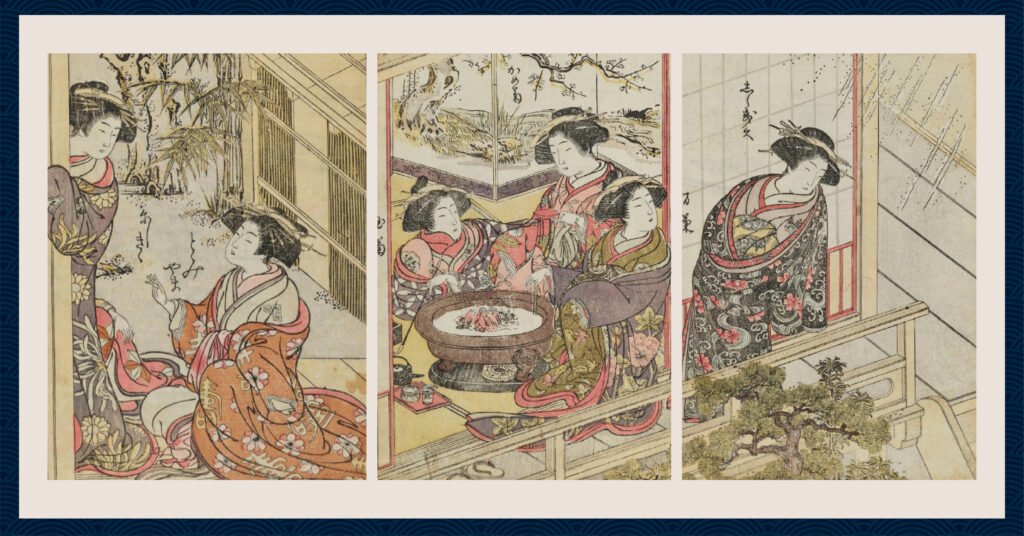

2. ColBase National Museum Collection Database: “Seirō Bijin Awase Sugata Kagami”

This work by Kitao Shigemasa and Katsukawa Shunchō captures not only beautiful courtesans but also interior scenes of Yoshiwara and everyday expressions, offering glimpses into the period’s environments and landscapes.

The artists’ attention to detail in depicting interior furnishings, tatami mat patterns, shoji screen constructions, and the arrangement of household items makes this collection particularly valuable for understanding Edo-period interior design. These visual elements provide contemporary designers with authentic reference materials for recreating traditional Japanese spaces.

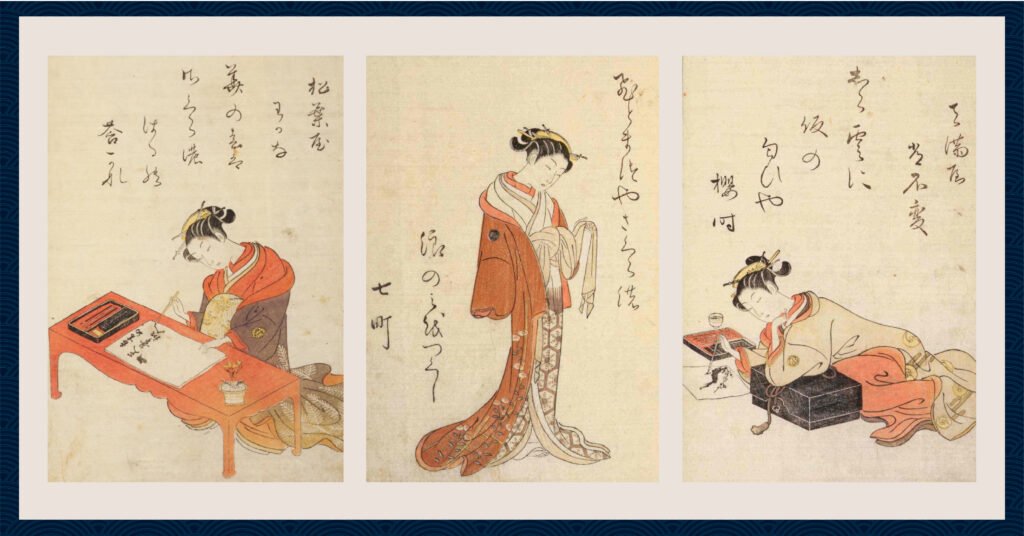

3. Metropolitan Museum Digital Collection: “Yoshiwara Courtesans: A New Mirror Comparing the Calligraphy of Beauties”

This fascinating work by Kitao Masanobu pairs portraits of courtesans with reproductions of their calligraphy. It highlights the fact that courtesans were valued not only for their beauty but also for their artistic and literary accomplishments.

The book features leading courtesans of the day, such as Hinazuru, who selected a poem by the 10th-century poet Fujiwara Sanesada: “I turn to look for the summer warbler singing, but there is nothing but the moon left at dawn,” and her colleague Chozan, who chose an anonymous poem from the 9th-century Kokinshū anthology: “The flying geese leave the spring mists behind without a glance—perhaps they are simply used to living in a village without flowers.”

These selections reveal the courtesans’ refined aesthetic sensibilities and deep cultural knowledge, aspects of Edo Yoshiwara culture that extended far beyond physical beauty.

Applying Edo Yoshiwara Culture to Contemporary Design

The lost world of Edo Yoshiwara culture can never be recreated, but through visual materials like ukiyo-e, its aesthetic sensibilities and stylistic elements continue to influence us today.

In the realms of design and illustration, ukiyo-e depicting Yoshiwara offers a wealth of inspiration. From portraiture techniques and composition methods to color combinations and decorative motifs, contemporary creators can learn much from these historical works.

The free downloadable resources introduced in this article should prove valuable for those exploring the rich expressions of Japanese culture. By reinterpreting the unique aesthetic world of Edo Yoshiwara culture—where splendor and melancholy intersected—through a contemporary sensibility, designers can connect traditional beauty with new creative directions.

Explore More Free Downloadable Resources

If you’re interested in discovering more freely downloadable historical Japanese art resources for your creative projects, click the banner below. Our curated collection includes additional ukiyo-e prints, kimono pattern books, and rare illustrated manuscripts that offer authentic glimpses into Japan’s artistic heritage. Continue your journey through the floating world and beyond with these carefully selected visual treasures from Japan’s golden age of woodblock printing.