The Tale of Genji, Japan’s timeless literary masterpiece, has captivated readers for over a millennium with its portrayal of aristocratic life and human emotions. Now, an extraordinary collection of Tale of Genji illustrations created by Edo-period master artist Hishikawa Moronobu has been digitized and made freely available by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. These exquisite circular compositions in “Genji Yamato-e Kagami” (Picture Mirror of Genji in Japanese Style) offer modern viewers a mesmerizing glimpse into the Heian court world as if peering through a time-transcending mirror. This remarkable resource provides a unique opportunity to explore the intersection of classical literature and early ukiyo-e artistry through these meticulously crafted Tale of Genji illustrations.

“Genji Yamato-e Kagami”: The Essence of Tale of Genji Illustrations by a Ukiyo-e Pioneer

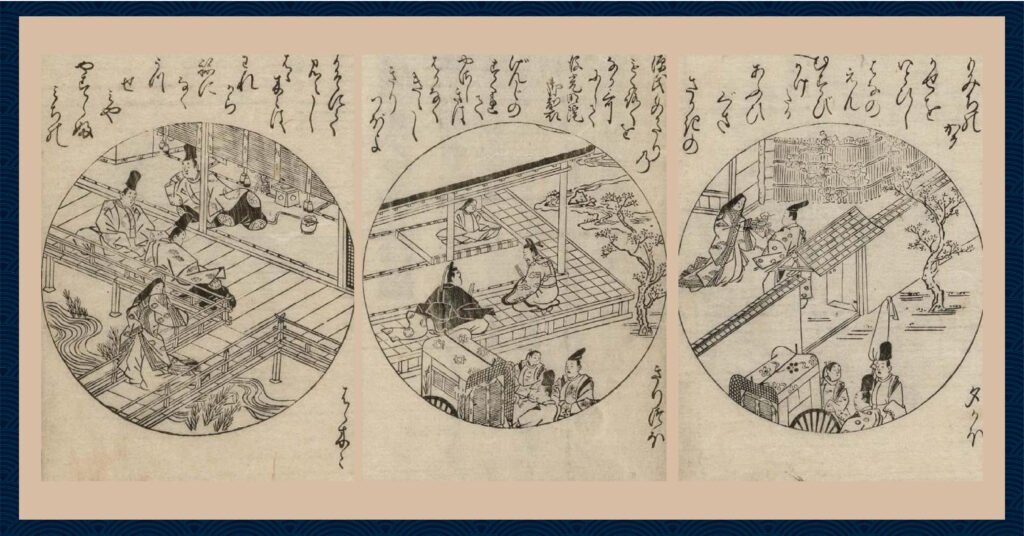

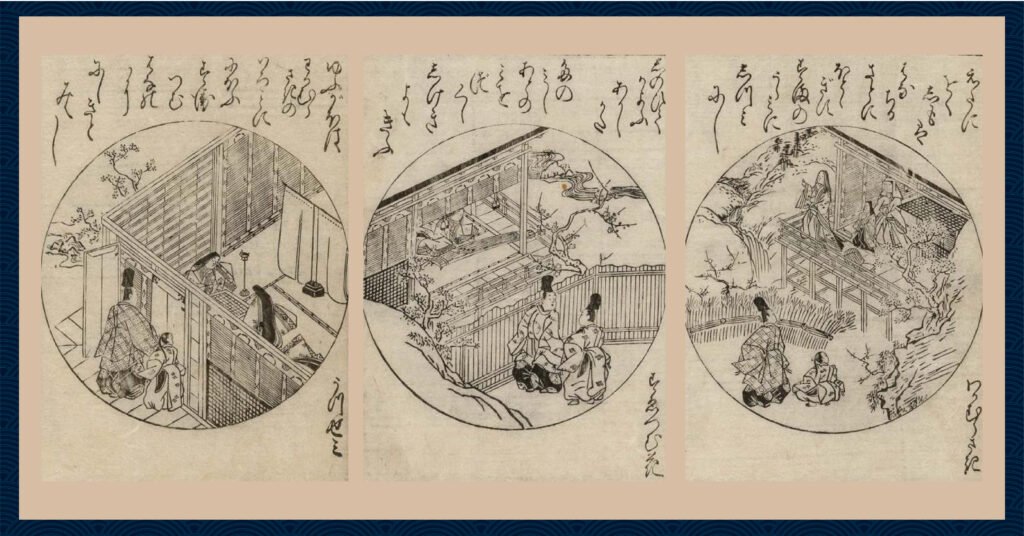

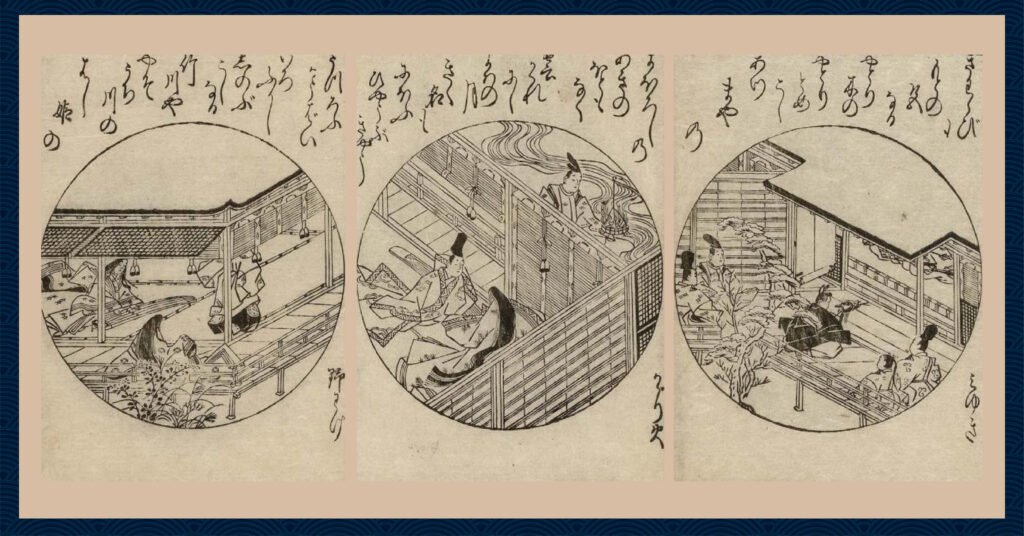

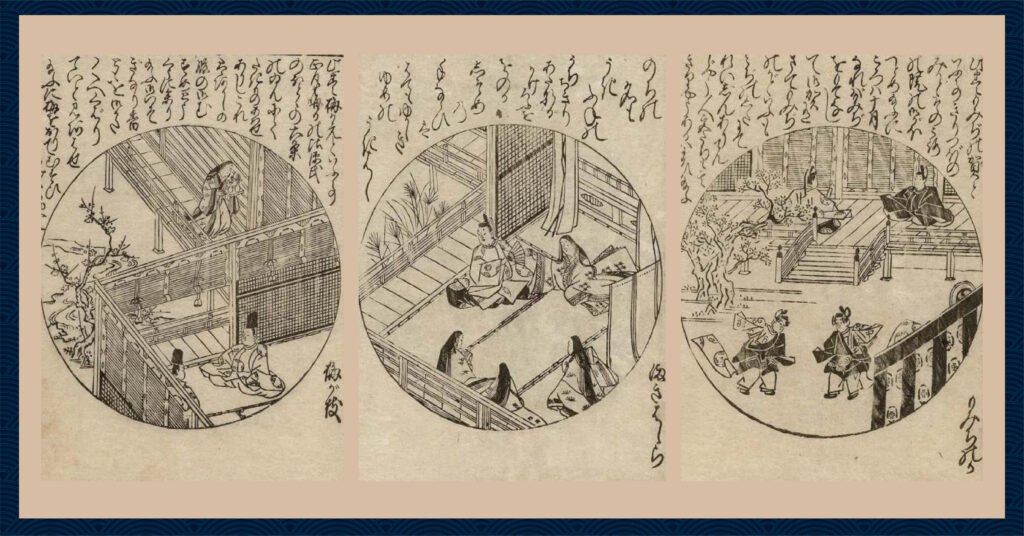

“Genji Yamato-e Kagami,” published in 1685 (Jōkyō 2), represents a significant achievement in the visual interpretation of Japan’s most celebrated literary work. Hishikawa Moronobu, widely regarded as the founding father of ukiyo-e, selected one iconic scene from each of the 54 chapters of The Tale of Genji and rendered them in circular compositions with remarkable precision. What makes this collection particularly valuable is the inclusion of long poems by Emperor Go-Kōmyō (the 110th emperor of Japan and third son of Emperor Go-Mizunoo) at the beginning of each section.

The preface explains the purpose of these Tale of Genji illustrations: “Though painters have created pictures of The Tale of Genji, they are difficult to clearly distinguish, so explanations of each chapter’s illustrations have been added along with imperial poems as headnotes, naming it Genji Picture Mirror for enjoyment and amusement.” The colophon further explains that the circular format inspired the name “kagami” (mirror): “This volume contains the genuine work of the Yamato-e artist called Hishikawa, thus the external title is Yamato-e Kagami (Japanese Picture Mirror), and because it is drawn inside circles, it is called ‘e-kagami’ (picture mirror) for this publication.”

Each half-page contains one Tale of Genji illustration, totaling 54 images throughout the work. The chapter name from The Tale of Genji appears in the lower right of each illustration, with poems in the header section. This arrangement allows readers to simultaneously appreciate the images, poetry, and narrative as an integrated aesthetic experience.

Hishikawa Moronobu: The Ukiyo-e Pioneer Behind These Tale of Genji Illustrations

Hishikawa Moronobu (c.1618-1694), the artist who created these Tale of Genji illustrations, was a pivotal figure in Japanese art history who is frequently credited as the “founder of ukiyo-e.” Born in Awa Province (present-day southern Chiba Prefecture) as the son of a gold-leaf artisan, Moronobu moved to Edo (present-day Tokyo) in his youth.

While scholars believe he studied the techniques of traditional Kano and Tosa schools, much of his artistic development appears to have been self-taught. Moronobu’s artistic output was remarkably diverse, encompassing bijinga (beautiful women pictures), yakusha-e (actor prints), fūzokuga (genre scenes of daily life), shunga (erotic art), and illustrated books. He is particularly notable for being among the first artists to use the term “ukiyo-e” (pictures of the floating world) to describe his artistic style.

For Western readers unfamiliar with ukiyo-e, this art form emerged in 17th-century Japan and depicted subjects from everyday life, initially in monochrome woodblock prints and later in the vibrant multi-colored prints that gained worldwide fame. The term “ukiyo” originally had Buddhist connotations of the transient, sorrowful world, but during the Edo period evolved to suggest the hedonistic, ephemeral nature of urban pleasures.

What distinguishes Moronobu’s Tale of Genji illustrations is his compositional skill in distilling complex narrative elements into visually comprehensible scenes and his sensitive depiction of psychological nuance through facial expressions. He cleverly simplified Heian-period (794-1185) aristocratic clothing and furnishings while maintaining their essential character, making these ancient tales accessible to Edo-period (1603-1868) audiences.

The circular format of the Tale of Genji illustrations in “Genji Yamato-e Kagami” creates a unique viewing experience, as if peering through a portal into the Heian court world. This circular composition, reflecting the “mirror” (kagami) in the title, suggests the act of gazing into another time and place—an innovative concept that would have fascinated Edo-period readers.

The Tale of Genji and Its Visual Tradition

To fully appreciate the significance of these Tale of Genji illustrations, it’s essential to understand both the literary masterpiece they interpret and the rich tradition of Genji-themed art that preceded Moronobu’s work.

The Tale of Genji, written around 1008 by court lady Murasaki Shikibu, is widely considered the world’s first psychological novel. Through its protagonist Hikaru Genji (“Shining Genji”) and his descendants, this monumental work portrays the aesthetic sensibilities and human drama of Heian aristocratic society across 54 chapters. The narrative incorporates 795 waka poems and features a complex web of characters and relationships.

For non-Japanese readers, The Tale of Genji can be compared to works like Proust’s “In Search of Lost Time” in its psychological depth and Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales” in its cultural significance, though it predates both by centuries. It remains a cornerstone of Japanese cultural identity and has been translated into numerous languages, most notably by Arthur Waley, Edward Seidensticker, Royall Tyler, and Dennis Washburn.

This literary masterpiece began inspiring visual artists shortly after its creation. The oldest known Tale of Genji illustrations appear in the “Genji Monogatari Emaki” (Tale of Genji Scrolls) created in the early 12th century at the request of Fujiwara no Takanaga, with paintings attributed to Fujiwara no Takachika and Fujiwara no Yukifusa. Surviving fragments, known as “Takanaga Genji,” are preserved in institutions including the Gotoh Museum and Tokugawa Art Museum.

Throughout the Kamakura (1185-1333) and Muromachi (1336-1573) periods, various schools produced Tale of Genji illustrations, including the Tosa school’s “Tosa Genji” and fan paintings in the Tosa style. The late 16th to early 17th centuries saw the creation of lavishly decorated works influenced by Momoyama-period aesthetic sensibilities, such as the “Funaki-bon Genji Monogatari Emaki” and “Sumiyoshi Jokei Hitsu Genji Monogatari Tegan,” which featured generous use of gold leaf.

Moronobu’s “Genji Yamato-e Kagami” represents both a continuation of this rich tradition of Tale of Genji illustrations and an innovative new approach that connected classical literature with the emerging popular culture of the Edo period. It stands as a transitional work that merges traditional Yamato-e aesthetics with the developing ukiyo-e sensibility.

Tale of Genji Illustrations at the Intersection of Yamato-e Tradition and Ukiyo-e Innovation

The title “Genji Yamato-e Kagami” incorporates the term “Yamato-e,” which refers to Japanese-style painting developed since the Heian period, as distinct from “Kara-e” or Chinese-style painting. Alternative terms include “Rikue,” “Wae,” “Wae,” and “Waiga,” often simply written in hiragana as “Yamato-e” to avoid confusion from variant kanji.

Yamato-e is characterized by Japanese subjects depicted using distinctively Japanese expressive techniques. These include sensitivity to seasonal themes and poetic sentiment, the “fukiuki-yatai” technique of separating scenes with gold clouds or mist, bird’s-eye view composition, and the stylized “hikime-kagibana” (slit eyes and hook nose) method of depicting facial features.

In contrast, ukiyo-e—the style pioneered by Moronobu—emerged as a new pictorial genre depicting urban life, customs, and the everyday experiences of common people in the Edo period. While early ukiyo-e inherited elements from the Yamato-e tradition, it pursued more populist and realistic expressions.

In “Genji Yamato-e Kagami,” Moronobu depicts The Tale of Genji’s Heian court scenes using a hybrid approach. While not adhering strictly to Yamato-e conventions, he incorporates the expressive liveliness characteristic of ukiyo-e in the gestures and facial expressions of his figures, along with innovative compositional elements. At the same time, his depictions of aristocratic clothing, furnishings, and architecture maintain respect for the Yamato-e tradition.

These Tale of Genji illustrations, fusing “Yamato-e tradition” with “ukiyo-e innovation,” successfully made classical literature more accessible to Edo-period commoners, demonstrating Moronobu’s genius in bridging high court culture with the emerging popular arts.

Experiencing Tale of Genji Illustrations Through Digital Archive

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston’s digitization of “Genji Yamato-e Kagami” represents a significant contribution to both Japanese art scholarship and creative inspiration for contemporary designers.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is renowned for having one of the world’s finest collections of Japanese art outside Japan. Its Japanese collection was largely formed through the efforts of 19th-century collectors William Sturgis Bigelow, Edward S. Morse, and Ernest Francisco Fenollosa, and includes outstanding examples of ukiyo-e prints, emakimono (picture scrolls), and folding screens.

The digitized Tale of Genji illustrations from “Genji Yamato-e Kagami” have been scanned at high resolution, allowing viewers to examine the finest details with remarkable clarity. This enables modern researchers and art enthusiasts to study Moronobu’s delicate line work, compositional techniques, and the craftsmanship of Edo-period woodblock printing up close.

For contemporary designers and illustrators, this digital archive of Tale of Genji illustrations provides an invaluable resource of authentic Japanese aesthetics and narrative visualization techniques. The circular compositional format, the elegant depiction of figures, and the harmonious integration of text and image offer timeless principles that remain relevant to modern visual communication.

The free availability of these Tale of Genji illustrations through the Boston Museum of Fine Arts website democratizes access to this cultural treasure. Specifically, these images can be found and downloaded at the following link.

Whether you are a scholar of Japanese art, a designer seeking authentic visual references, or simply an admirer of beautiful illustrations, this freely available digital archive of Tale of Genji illustrations offers a remarkable opportunity to connect with one of Japan’s most significant artistic and literary traditions through the lens of a pioneering ukiyo-e master.

Explore More Free Downloadable Resources

If you’re interested in discovering more freely downloadable historical Japanese art resources for your creative projects, click the banner below. Our curated collection includes additional ukiyo-e prints, kimono pattern books, and rare illustrated manuscripts that offer authentic glimpses into Japan’s artistic heritage. Continue your journey through the floating world and beyond with these carefully selected visual treasures from Japan’s golden age of woodblock printing.