From 1603, when Tokugawa Ieyasu established the shogunate in Edo (present-day Tokyo), until 1867, when Tokugawa Yoshinobu returned political power to the Emperor, Japan experienced an extraordinary period of peace lasting more than 260 years. Looking through world history, it’s rare to find such a long span of time without major warfare and with stable governance. This “Great Peace” produced what many consider the golden age of Japanese art history.

The political stability fostered economic development, allowing diverse artistic expressions to flourish, particularly in urban centers, satisfying the cultural desires of merchants, craftsmen, and the samurai class. Edo period paintings are characterized by their diversity and creativity. While preserving traditional styles, artists boldly experimented with new expressions, significantly expanding the range of painting genres and techniques.

This article explores Edo period paintings through three universal themes: “peace,” “living beings,” and “love,” examining how these artworks reflected Japanese aesthetics and sensibilities during this remarkable era.

The Diversity of Painting Styles Nurtured by Peace

Landscapes and Genre Paintings as Symbols of Peace

The peaceful era that followed the tumultuous Warring States period brought a sense of ease to people’s hearts. Released from the daily struggle for survival, people could turn their attention to observing and depicting their surroundings and daily lives. This leisure formed the foundation for the flourishing of landscape and genre paintings during the Edo period.

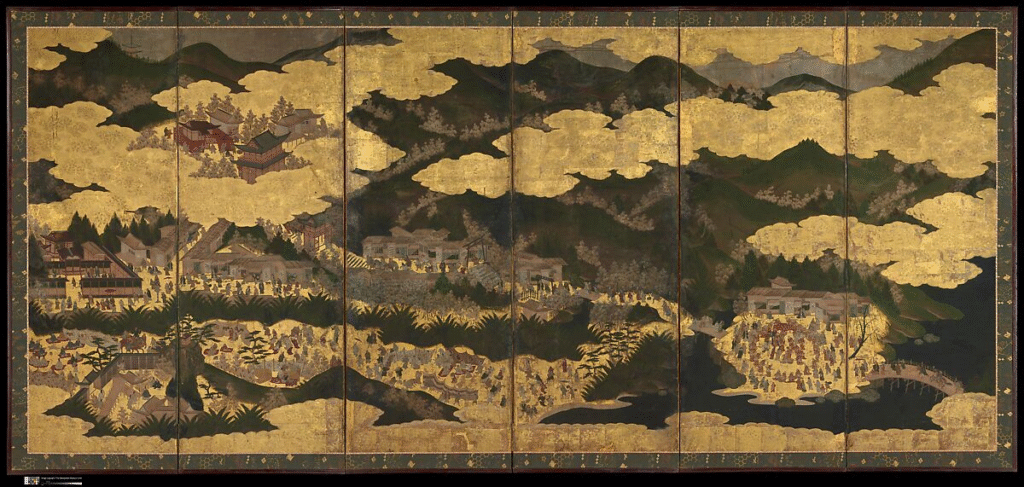

A notable example is the “Shugakuin Imperial Villa Screen” (early Edo period, Enpō era [1673-81]). This folding screen depicts the autumn landscape of the Shugakuin Imperial Villa, constructed by Emperor Gomizunoo after his abdication. It shows people of various social standings, from court nobles to commoners, including women, enjoying autumn outings such as viewing the red maple leaves. This artwork serves as historical testimony to the peaceful society and cultural activities of the time.

Art historian Tsuji Nobuo points out that early Edo period genre paintings share a common theme of “enjoying the peaceful era.” Images of people engaged in banquets, cherry blossom viewing, or autumn leaf viewing symbolize the joy of a society freed from the anxieties of war.

Urban Culture Development and Painting

Economic prosperity during the Edo period led to the flourishing of urban culture, centered in Kyoto, Osaka, and Edo. Particularly, Edo rapidly developed as the headquarters of the Tokugawa shogunate, growing into one of the world’s largest cities with a population exceeding one million by the early 18th century.

This urban development fostered the birth and spread of new painting styles. Most notable was the establishment and evolution of ukiyo-e (woodblock prints depicting the “floating world”). Early ukiyo-e, beginning with Hishikawa Moronobu, featured the lives and customs of people living in Edo. When Suzuki Harunobu established the nishiki-e technique (multi-colored woodblock prints), ukiyo-e exploded in popularity, becoming the representative visual art of Edo’s commoner culture.

Meanwhile, in Kyoto, the Rinpa school developed against the backdrop of traditional elegant culture, passing from Tawaraya Sōtatsu to Ogata Kōrin, and then to Sakai Hōitsu in the late Edo period. Rinpa artists expressed themes drawn from classical literature in a decorative style effectively using gold and silver pigments, embodying refined urban aesthetics.

Kobayashi Tadashi, a researcher at the Tokyo National Museum, states that “Edo period paintings reflect the diverse values of a peaceful society.” The flourishing of unique cultures within each social stratum, despite the rigid class system, created the richness of Edo period paintings.

A Deep Gaze at Life—”Living Beings” in Edo Period Paintings

The Fusion of Scientific Observation and Artistic Expression

A notable characteristic of Edo period paintings is the increase in works depicting plants and animals in detail and realism. This trend was supported by the scholarly attitude of objectively observing and recording nature—an approach that could only develop during peaceful times.

Watanabe Kazan’s (1793-1841) “Album of Insects and Fish” exemplifies this fusion of scientific spirit and artistic expression. A samurai from Tahara Domain in Mikawa Province, Kazan was also a scholar of Rangaku (Western learning through Dutch studies) and a talented literati painter who combined Western observational techniques with Eastern expressive methods.

This album depicts insects and fish in meticulous detail, but it’s more than just natural history illustration. Kazan was a tragic figure who faced shogunate persecution for his Rangaku research and was implicated in the “Bansha no goku” (Barbarian Studies Incident). He gave this album to his disciple Tsubaki Chinzan about one month before taking his own life. While superficially a precise depiction of nature, the work contains political metaphors suggesting the crisis of late Edo Japan threatened by Western powers, through the “survival of the fittest” natural world.

Art critic Takashina Shūji commented that “Kazan’s paintings are highly intellectual creations where science, art, and political thought intersect.”

Itō Jakuchū and the Lineage of Eccentric Painters

Itō Jakuchū (1716-1800), a representative painter of the mid-Edo period, is known as an “eccentric painter” for his highly original style. Born to a vegetable wholesale merchant family in Kyoto, Jakuchū began painting seriously only after turning 40, yet created astonishing works primarily featuring animals and plants through his extraordinary observational skills and innovative techniques.

His “Peacock and Phoenix” painting, which created a sensation when rediscovered in 2016 after 83 years, is considered a relatively early work created before Jakuchū turned 42. Nevertheless, it already displays glimpses of his talent. The meticulous depiction, down to each individual peacock feather, conveys a sense of reverence for the mysteries of life.

Jakuchū’s masterpiece “Colorful Realm of Living Beings” (housed in the Sannomaru Shōzōkan Museum, Imperial Palace) consists of 30 scrolls depicting familiar animals and plants like chickens, carp, flowers, and vegetables with supernatural precision. In these works, Jakuchū goes beyond scientific observation to reconstruct his subjects from a unique perspective, successfully visualizing the vitality of life.

Art historian Tsuji Nobuo describes Jakuchū as “a painter with a reality that transcends reality” and notes that his unusual expression often parallels contemporary art. Such unconventional expression could only be tolerated in a stable society.

Expressions of Affection for Familiar Animals

Edo period paintings include numerous works expressing affection for familiar animals like dogs and cats, not just exotic or fantastical creatures like peacocks and phoenixes.

Works like Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s (1798-1861) “Fashionable Cats at Play with Temari Balls” depict anthropomorphized cats in charming ways, indicating people’s fondness for cats at that time. Similarly, works like Tawaraya Sōtatsu’s “Dog” and Maruyama Ōkyo’s “Puppies” convey affection for dogs as pets.

The Japanese people of the Edo period valued symbiotic relationships with various living beings, not just humans, and expressed respect for life by preserving their images in paintings. This view of life is deeply connected to the Japanese perception of nature and can be seen as the source of contemporary environmental consciousness.

Various Forms of Love Expressed in Paintings

Remembering the Absent—The Sentiment of the “Tagasode Screen”

One characteristic expression in Edo period paintings is the technique of suggesting a person’s presence without directly depicting them. The “Tagasode Screen” (“Whose Sleeves?”) is a typical example of this approach.

This theme, which arranges clothing and personal items on a clothes rack to evoke the image of their owner, symbolizes the suggestiveness and emotional depth unique to Japanese art. In the “Tagasode Screen” housed in the Suntory Museum of Art, the right screen’s center depicts a small kimono with wisteria flower patterns on mist (a Noh costume), while the right edge shows a box presumed to contain Noh masks, suggesting the owner was someone who appreciated the Noh theater.

This expressive technique reflects the Japanese aesthetic sensibility that values “mono no aware” (the pathos of things). The sensitivity of reflecting on absent people through objects and appreciating their transience is deeply connected to the tradition of “monogatari” (narrative) in Japanese literature. This aesthetic, which prioritizes evoking emotion through “suggestion” rather than direct expression, represents a uniquely Eastern approach not found in Western painting.

Art critic Takashina Shūji states, “The Tagasode Screen embodies the essence of Japanese art in its paradoxical method of highlighting presence through absence.”

Expressions of Family Love and Children

Edo period paintings also include many works expressing family bonds and affection for children. Screen paintings created as part of a bride’s trousseau for samurai families contained wishes for prosperity and happiness in the newlyweds’ home life.

Works depicting seasonal events like the Doll Festival or the Boy’s Day Festival reveal parents’ hopes for their children’s healthy growth. In Katsushika Hokusai’s “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji” series, the foreground of “Clear Day with a Southern Breeze” (commonly known as “Red Fuji”) depicts the scene of drying silk cocoons, juxtaposing the custom of praying for children’s growth with the eternity of Mount Fuji in an excellent composition.

Romantic Emotions and the World of Bijinga

In Edo period ukiyo-e, bijinga (pictures of beautiful women) was one of the most popular genres. Refined through the work of artists from Hishikawa Moronobu to Suzuki Harunobu, Kitagawa Utamaro, Keisai Eisen, and Utagawa Kunisada (Toyokuni III), bijinga reflected not just women’s physical appearances but also the romantic sensibilities and idealized female images of the time.

Utamaro’s bijinga, in particular, emphasized not only external beauty but also the expression of delicate inner emotions. His technique of condensing women’s psychology into momentary expressions or gestures, as seen in his “Beauty Looking Back,” is considered the pinnacle of Edo period ukiyo-e bijinga. Art critic Takashina Shūji notes that “the women depicted by Utamaro suggest their inner emotional world through gazes and subtle facial movements.”

During the Edo period, guidebooks called “Yoshiwara Saiken” were published, and many ukiyo-e depicted courtesans from the pleasure quarters. Works like Suzuki Harunobu’s “Beauties of the Green Houses Compared” and Kitagawa Utamaro’s “Twelve Hours in the Pleasure Quarters” expressed the sentiment of fleeting love through idealized beauty.

The popularity of such bijinga was made possible by the “cultural refinement of romance” that emerged with the maturation of commoner culture and economic prosperity. Only in a peaceful society could people afford to elevate romantic emotions—a universal human sentiment—into an art form for appreciation.

Techniques and Aesthetics of Edo Period Paintings

Coexistence of Diverse Schools

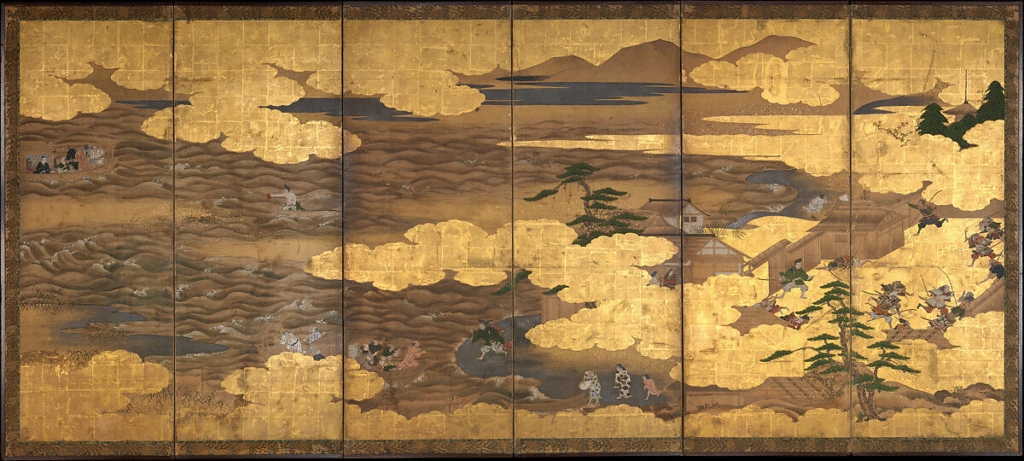

The richness of Edo period paintings lies in how various schools developed uniquely while coexisting harmoniously. The Kanō school, which rose as official painters to the Tokugawa shogunate; the Tosa school, which inherited the tradition of court painters; literati painting influenced by Chinese painting; ukiyo-e born from commoner culture; and the Rinpa school pursuing distinctive decorative qualities—this multiplicity of coexisting styles reflects the cultural pluralism possible only in a peaceful society.

Kawano Motoaki, Professor Emeritus at Tokyo University of the Arts, points out that “in Edo period paintings, schools with seemingly different aesthetic sensibilities developed while mutually influencing each other.” For example, Yosa Buson, known as a literati painter, also incorporated ukiyo-e techniques, while ukiyo-e artist Katsushika Hokusai incorporated decorative elements reminiscent of the Rinpa school in his works.

In this way, peaceful societies tend to value artistic “diversity” over “purity,” which became the wellspring for the rich expressions found in Edo period paintings.

Aesthetics of Line and Color

The importance of “line” in traditional Japanese painting continued in Edo period paintings. Ukiyo-e prints, in particular, fundamentally employ linear expression that clearly delineates forms with outlines—a fundamentally different approach from Western painting’s representation of three-dimensionality through light and shadow.

Meanwhile, decorative paintings represented by the Rinpa school feature bold flat compositions with brilliant colors and gold and silver pigments, emphasizing simplified forms through “patterns” and color contrast. Ogata Kōrin’s “Red and White Plum Blossoms” (MOA Museum of Art) and Sakai Hōitsu’s “Summer and Autumn Grasses” (Tokyo National Museum) exemplify this approach.

In the late Edo period, Western painting techniques also began to influence Japanese art, with copper engravings and oil paintings produced by artists like Shiba Kōkan and Aōdō Denzen. This absorption of Western techniques further expanded the expressive range of Edo period paintings.

Art historian Kawano Motoaki states, “Edo period painters possessed both aspects of inheriting traditional techniques and absorbing new ones.” The balance between conservation and innovation maintained throughout the development of Edo period paintings offers many suggestions for contemporary design and artistic expression.

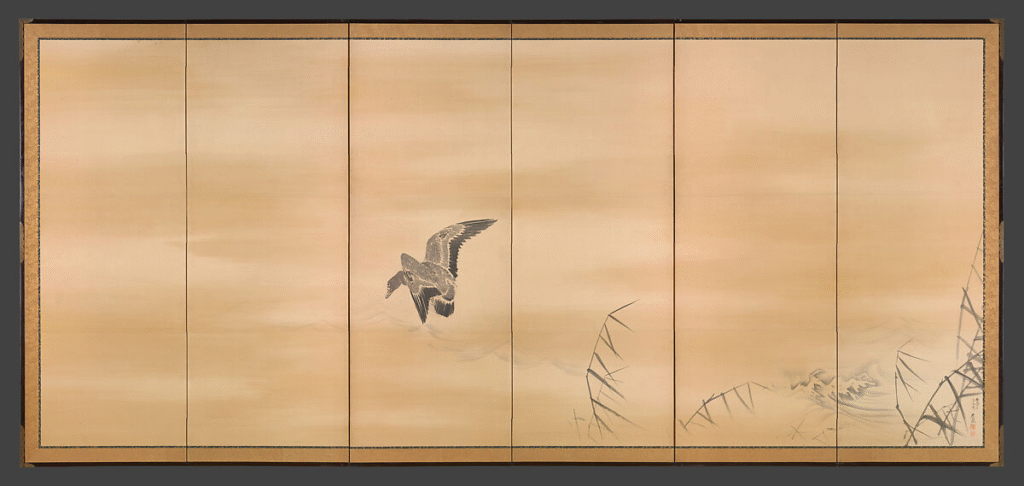

Aesthetics of Empty Space and Omission

In Edo period paintings, especially ink paintings and literati paintings, “empty space” or unpainted areas were also important expressive elements. Works like Maruyama Ōkyo’s “Pine Trees in Snow” (Mitsui Memorial Museum) capture the essence of the subject with minimal depiction, expressing the stillness of snow through empty space—a characteristic of Japanese art.

Expressive omission is another important feature of Edo period paintings. For example, Tawaraya Sōtatsu’s “Wind God and Thunder God Screens” (Kennin-ji Temple) completely omits the background, depicting only the two deities, thereby accentuating their presence.

This aesthetics of “empty space” and “omission” reflects a uniquely Japanese sensibility that finds meaning not only in “what is visible” but also in “what is invisible,” actively stimulating the viewer’s imagination.

Art critic Takashina Shūji notes that “empty space in Edo period paintings is not mere blankness but a creative space completed in the viewer’s mind.” This concept holds universal value that connects to contemporary minimalist design and web design emphasizing white space.

The Spirit of Edo Period Paintings Inherited in Modern Times

Universal Values Transcending Time

The diverse painting expressions that flourished during the Edo period are not merely historical heritage but continue to exert significant influence on contemporary art and design. The flat composition and bold framing of ukiyo-e influenced Western modern painting through Japonisme, with ripple effects extending to today’s graphic design.

The delicate observation of nature and respect for life evident in Edo period paintings also resonate with contemporary environmental consciousness. The deep insight and expression toward living beings demonstrated by Itō Jakuchū and Watanabe Kazan could serve as a philosophical foundation for today’s biodiversity conservation.

Furthermore, expression through “empty space” and “omission” teaches us the value of deliberately reducing information in our information-saturated modern society. This connects with contemporary design concepts like minimalism and flat design.

Reevaluation of Edo Period Paintings in the Digital Age

In recent years, digital technology development has made it possible to view masterpieces of Edo period paintings, once viewable only in museums, anytime through high-definition digital images. Institutions like the Tokyo National Museum and Kyoto National Museum have advanced the digitization of their collections, making them available on their websites.

Digital art and content based on Edo period paintings motifs have also increased, reintroducing the charm of these historical works to younger generations. The “Jakuchū boom” of 2016 became a social phenomenon, amplified by social media sharing, testifying to the contemporary value of Edo period paintings being widely recognized.

Digital artist Daito Manabe states, “The aesthetic sense of Edo period paintings provides significant inspiration for contemporary digital art and media art.” This dialogue of beauty across time and space is generating new creations in the modern era.

How Designers Can Utilize Edo Period Paintings Resources

For contemporary designers, Edo period paintings are not merely sources of inspiration but valuable materials that can be used in actual production. Many Edo period works have entered the public domain as their copyright protection periods have expired, allowing free use, including commercial applications.

For example, the following websites offer high-quality images of Edo period paintings for free:

- Tokyo National Museum Image Search [JP]

- National Diet Library Digital Collection

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Ukiyo-e Collection

By utilizing these resources, designers can create original designs in various fields, including Japanese-style design, logos, packaging, websites, and apparel.

However, when processing and using these images, it’s important to respect the cultural value of the works and deepen understanding of the original artists’ intentions and historical background. Understanding the delicate aesthetics and cultural context of Edo period paintings will enable deeper design expressions.

Edo period paintings that bloomed during the approximately 260 years of peace expressed Japanese aesthetics and sensibilities through the universal themes of “peace,” “living beings,” and “love.” Though diverse in techniques and styles, what runs through them all is a respect for life, harmony with nature, and a sensibility that delicately captures the nuances of human relationships.

In contemporary society, we can learn much from Edo period paintings. In our rapidly changing information society, the quiet world of beauty demonstrated by these historical artworks brings peace to our hearts and creative inspiration.

Utilizing the rich expressive world of Edo period paintings in contemporary creative activities holds significant meaning for the inheritance and development of Japanese culture. Not merely preserving past heritage, but reinterpreting it in contemporary contexts and connecting it to new creations—that is perhaps the true way to honor the legacy entrusted to us by the painters of the Edo period.

Explore More Free Downloadable Resources

If you’re interested in discovering more freely downloadable historical Japanese art resources for your creative projects, click the banner below. Our curated collection includes additional ukiyo-e prints, kimono pattern books, and rare illustrated manuscripts that offer authentic glimpses into Japan’s artistic heritage. Continue your journey through the floating world and beyond with these carefully selected visual treasures from Japan’s golden age of woodblock printing.