In Japanese traditional culture, the relationship between tattoos and woodblock prints represents one of the most fascinating artistic collaborations in history. Japanese Traditional Tattoo, known as Irezumi, and Ukiyo-e prints emerged from the same cultural environment of the Edo period (1603-1868), creating a distinctive aesthetic world through their mutual influence. This exploration traces the surprising etymology and historical evolution of Irezumi while uncovering its artistic exchange with Ukiyo-e.

Chapter One: Japanese Aesthetics in Tattoo Terminology

The Birth of Modern Terminology

The term commonly used today for Japanese Traditional Tattoo involves writing the characters “刺青” (shisei) while pronouncing them as “irezumi” – a relatively recent linguistic development. According to Ichiro Morita’s comprehensive study on tattoos published in 1966, this written form became widespread only during the late Meiji period (1868-1912). The term gained particular prominence through two cultural milestones: Junichiro Tanizaki’s 1911 novella titled “Shisei” and the 1932 kabuki theater production “Shisei Kigu” by Shin Hasegawa at the prestigious Kabukiza.

The etymology of this term likely stems from the visual appearance of the tattooed ink beneath the skin, which takes on a bluish hue. This naming convention reflects a distinctly Japanese color sensibility and aesthetic consciousness that transcends simple body decoration. The sophisticated wordplay inherent in this terminology suggests pictorial Irezumi rather than basic markings or symbols.

Historical Evolution of Tattoo Terminology

The linguistic history surrounding Irezumi provides insights into changing social attitudes toward Japanese Traditional Tattoo. Ancient terminology included “gei” (黥), meaning “spotted or marked body.” This evolved into various terms including “bunshin” (文身 – patterned body), “horimono” (彫物 – carved objects), and “irebokuro” (入黒子 – inserted beauty marks).

Regional variations during the Edo period reveal cultural nuances: while Edo (modern-day Tokyo) residents called tattoos “horimono,” the Kyoto-Osaka region preferred “irebokuro.” This latter term derived from the practice of artificially creating beauty marks, demonstrating how Japanese Traditional Tattoo terminology reflected distinct regional cultural practices and aesthetic preferences.

Chapter Two: The Water Margin Revolution

The Emergence of Pictorial Irezumi

The transformation of Japanese Traditional Tattoo from simple symbols to elaborate pictorial art coincided with the introduction of the Chinese epic “Water Margin” (known as Suikoden in Japanese). First translated into Japanese in 1757, this tale of heroic outlaws captivated Edo audiences and fundamentally changed the nature of Irezumi.

Among the Water Margin’s cast of 108 heroes, several characters particularly captured the imagination of Edo citizens:

- Shi Jin, the Nine-Dragon: A warrior decorated with nine blue dragons across his body

- Lu Zhishen, the Flowery Monk: An unconventional Buddhist monk bearing elaborate floral tattoos

- Zhang Shun, the White Stripe in the Waves: A master swimmer renowned for aquatic feats

These heroic figures became aspirational models for Edo townspeople, who began adorning their bodies with similar designs to embody the spirit of these legendary warriors. This marked the beginning of narrative-based Japanese Traditional Tattoo art.

Ukiyo-e Masters’ Creative Interpretations

The year 1827 marked a watershed moment when Utagawa Kuniyoshi released his “Popular Water Margin” series of Ukiyo-e prints. Kuniyoshi’s dynamic hero portraits transcended mere illustration, incorporating distinctly Japanese aesthetic elements into these Chinese tales. His work established Ukiyo-e as the primary visual source for Irezumi designs.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi further refined this artistic dialogue through his series including “Beautiful and Brave Water Margin,” “Heroic Water Margin,” and “Modern Tales of Chivalry.” These Ukiyo-e masterworks featured sophisticated compositions and color schemes that made them invaluable as tattoo design references. The relationship between Japanese Traditional Tattoo and Ukiyo-e reached its artistic zenith through these collaborative influences.

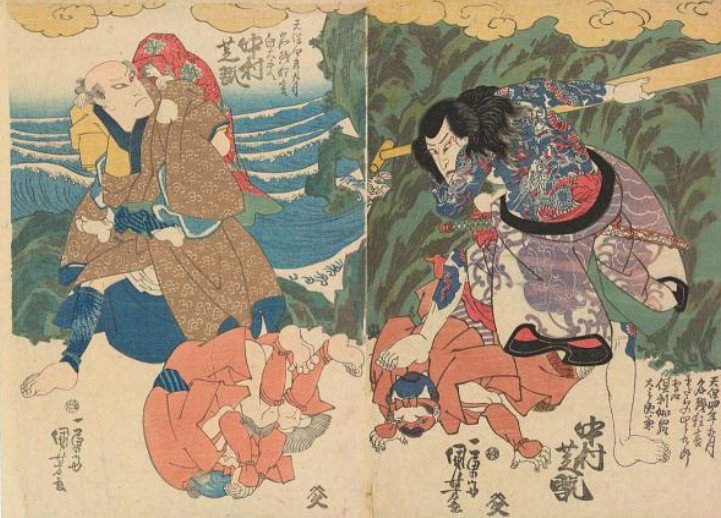

Toyohara Kunichika Japanese 1875

Chapter Three: Symbolic Meanings in Design Motifs

The Heroes and Warriors Tradition

The subjects selected for Irezumi designs profoundly reflect Japanese spiritual values and social aspirations. Military commanders and legendary heroes dominated tattoo imagery, particularly those representing success stories and social advancement:

- Historical figures like Ushiwakamaru (young Minamoto no Yoshitsune), Kato Kiyomasa, and Kusunoki Masashige

- Legendary warriors including Asahina and Nitta Shiro

- Popular kabuki theater characters such as the Shiranami Five thieves

These choices reflected the rigid social hierarchy of Edo Japan, where common people could only dream of heroic transformation and social mobility.

Religious and Folkloric Dimensions

Religious and folkloric motifs occupy a significant place in Japanese Traditional Tattoo iconography. Buddhist imagery ranging from Kannon (the Goddess of Mercy) and Benzaiten (Goddess of Fortune) to the fierce Wind and Thunder Gods appears alongside Shinto themes like Susanoo-no-Mikoto. This religious diversity in Irezumi reflects Japan’s syncretic spiritual landscape, where Buddhism and Shintoism coexist harmoniously.

Natural World Symbolism

Animal and plant motifs in Japanese Traditional Tattoo carry profound symbolic meanings deeply rooted in East Asian culture:

- Dragons: Embodying power and imperial authority, often associated with water and weather control

- Koi Carp: Representing perseverance and aspiration, based on the Chinese legend of carp transforming into dragons

- Peonies: Symbolizing wealth, honor, and feminine beauty as the “king of flowers”

- Cherry Blossoms: Crystallizing Japanese aesthetic consciousness through their ephemeral beauty

Each design element in Ukiyo-e-inspired Irezumi carries layers of cultural meaning that Western observers might not immediately recognize.

Final Chapter: The Continuing Legacy of Beauty

Investigating the relationship between Japanese Traditional Tattoo and Ukiyo-e reveals profound insights into Japanese culture. These art forms transcend mere decoration or entertainment, serving as mirrors reflecting Japanese aesthetics, spirituality, and social perspectives. The intricate bond between Irezumi and Ukiyo-e demonstrates how popular culture achieved artistic sophistication in Edo Japan, creating a unique form of body art without parallel in world history.

For contemporary creators and designers, this tradition remains vibrantly relevant. As globalization accelerates, understanding cultural uniqueness and reinterpreting it for modern contexts becomes increasingly valuable. The artistic dialogue between Japanese Traditional Tattoo and Ukiyo-e continues to inspire new creative expressions, bridging historical traditions with contemporary innovation.

This series on “Japanese Traditional Tattoo and Ukiyo-e” will continue exploring these artistic relationships from various perspectives. Future installments will examine specific Ukiyo-e artists’ contributions to tattoo design, analyze regional variations in Irezumi traditions, and investigate how contemporary artists reinterpret classical themes for modern audiences.

References and Resources

- Morita, Ichiro. “Irezumi” (Tattoo). Zufu Shinsha, 1966.

- “Genshoku Nihon Irezumi Taikan” (Color Encyclopedia of Japanese Tattoos). Haga Shoten, 1973.

- Ryugendo Archives. “Irezumi Design Explanations.”

Editorial Note

This article draws extensively from Ichiro Morita’s foundational 1966 study, which remains essential reading for understanding Japanese Traditional Tattoo history. The interpretations presented here aim to make this scholarship accessible to contemporary international audiences while respecting the original research’s academic integrity.