In Studio Ghibli’s masterpiece Princess Mononoke (1997), no character embodies mystery and divine power quite like the Shishigami Forest Spirit. This enigmatic deity, central to the film’s narrative, leaves viewers with an indelible impression while remaining shrouded in profound mystery. What many international audiences may not realize is that this Shishigami Forest Spirit draws inspiration from multiple deities and spiritual beings deeply rooted in Japanese mythology and ancient folklore.

This article explores three significant Japanese mythological creatures that likely influenced Miyazaki’s creation of the Forest Spirit: the Kudan (件), the Shinroku (神鹿 – divine deer), and Amenokaku (天迦久神 – a deer deity from ancient Japanese texts). Through understanding these traditional figures, we can appreciate how Hayao Miyazaki transformed Japan’s spiritual heritage into a powerful symbol for contemporary animation.

The Multifaceted Nature of the Shishigami Forest Spirit

To understand the mythological roots, we must first examine the Shishigami Forest Spirit as depicted in Princess Mononoke. The film presents this deity as the god of life and death, possessing a dual nature – appearing as a peculiar deer-like creature during the day and transforming into a massive humanoid giant called the Nightwalker (Daidarabotchi) after dark.

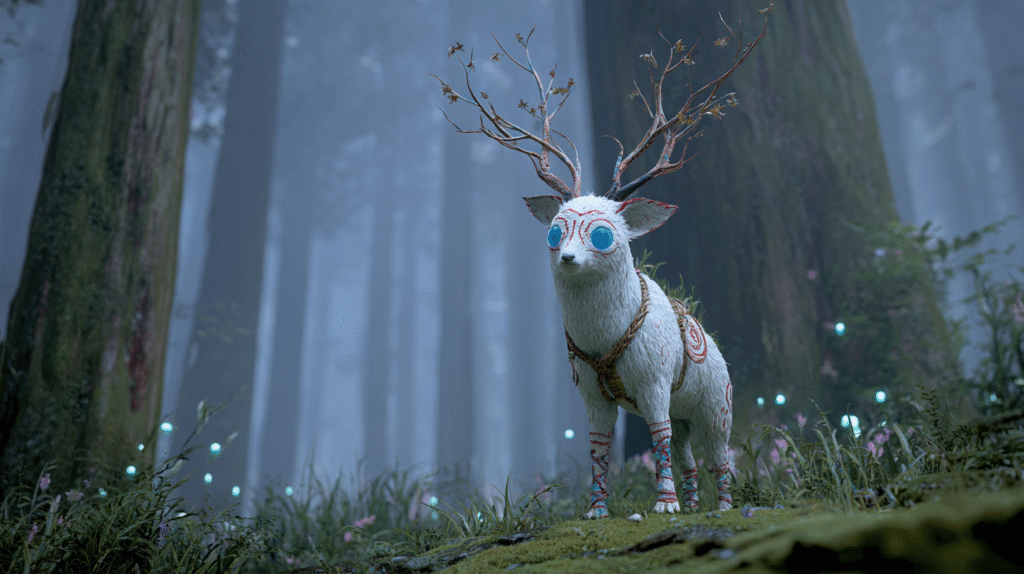

The Forest Spirit’s appearance is far from that of an ordinary deer. Its face resembles a baboon with distinctly human features, while its body combines characteristics of various animals – goat-like ears, cat-like eyes with blue markings, an ostrich-like gait with three-toed hooves, and antlers resembling tree branches. This chimeric design, mixing features from multiple creatures, represents a deliberate artistic choice reflecting the complex nature of Japanese mythological creatures.

Kudan: The Prophetic Human-Faced Beast

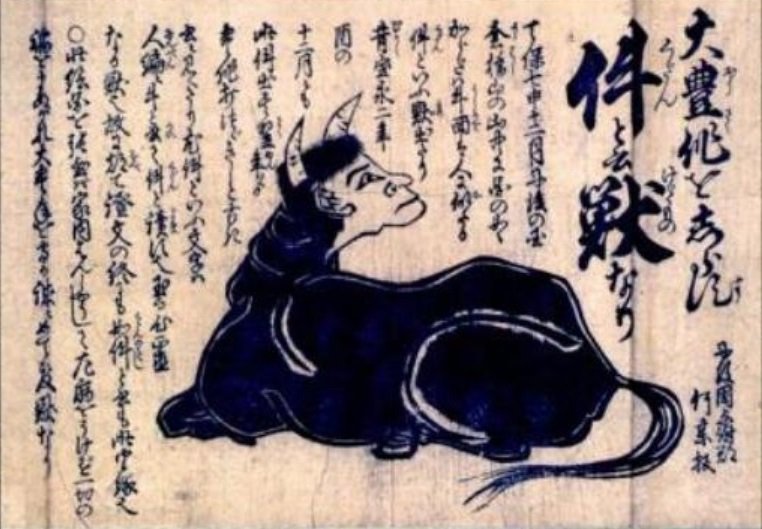

One of the most striking features of the Shishigami Forest Spirit is its human face on an animal body, a characteristic shared with a Japanese mythological creature known as Kudan (件). In Japanese folklore, particularly from the late Edo period through the Meiji era, Kudan appears as a creature with a cow’s body and a human head – essentially the reverse of the Western Minotaur.

The Kudan possesses remarkable abilities in Japanese mythology. Born with the gift of speech, it delivers prophecies immediately after birth before dying shortly thereafter. These prophecies, particularly those foretelling disasters or calamities, are said to be infallible. The creature’s name itself carries interesting etymological significance – when the kanji character 件 is deconstructed, it separates into 人 (person) and 牛 (cow), suggesting the character itself embodies the creature’s dual nature.

Historical accounts of Kudan sightings were primarily concentrated in western Japan. The creature gained such cultural significance that it appears in various literary works, including Uchida Hyakken’s 1920 short story “Kudan” and Komatsu Sakyo’s “Kudan no Haha” (The Kudan’s Mother), later adapted into manga by Shotaro Ishinomori. These modern interpretations often emphasize the creature’s role as a harbinger of doom, particularly during times of war or natural disaster.

The Shishigami Forest Spirit shares this uncanny quality of possessing a human-like face that reveals nothing of its thoughts or intentions. This inscrutability mirrors the Kudan’s role as a being beyond human comprehension, one that bridges the natural and supernatural worlds. In Princess Mononoke mythology, the Forest Spirit similarly operates beyond human understanding, controlling life and death with apparent indifference to human concerns.

Shinroku: The Sacred Deer Tradition

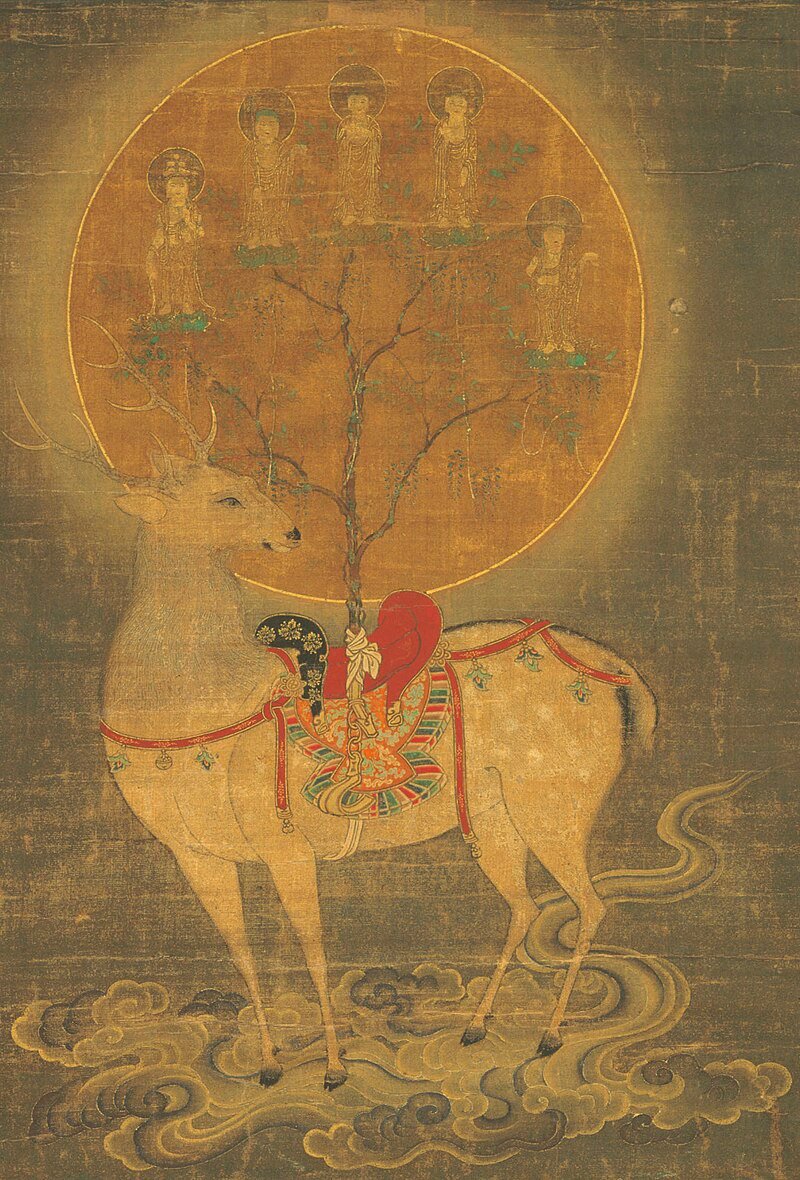

The deer has occupied a sacred position in Japanese culture since ancient times, and the concept of Shinroku (神鹿) – divine or sacred deer – provides another crucial element in understanding the Shishigami Forest Spirit. The term Shinroku refers to deer possessing spiritual power or those serving as messengers of the gods.

The most famous example of Shinroku can be found at Kasuga Taisha shrine in Nara, where over a thousand deer roam freely as protected sacred animals. According to legend, the thunder deity Takemikazuchi arrived at Kasuga Taisha riding a white deer from Kashima Shrine, establishing the deer’s divine status. To this day, these deer are considered national treasures and divine messengers, treated with reverence by visitors and locals alike.

Various regions throughout Japan preserve legends of divine deer. One particularly relevant tale from Kamishima (possibly Nozaki Island) tells of an skeptical hunter who attempted to shoot a magnificent deer, dismissing local beliefs about the animals’ sacred nature. After firing two unsuccessful shots, he prepared for a third when countless deer suddenly emerged from nowhere, surrounding him with piercing gazes until he fled in terror.

The Shishigami Forest Spirit embodies this tradition of the sacred deer, serving as the master of the “Forest of the Shishigami” and occasionally appearing among ordinary deer herds. This portrayal reflects the Japanese concept of kami (divine spirits) as beings that exist within nature while transcending it, demanding both reverence and fear from humans who encounter them.

Amenokaku: The Boundary-Crossing Deer Deity

The third and perhaps most mythologically significant influence comes from Amenokaku (天迦久神), a deer deity appearing in the Kojiki, Japan’s oldest extant chronicle of myths and legends, compiled in 712 CE. This deity provides insight into the more esoteric aspects of the Shishigami Forest Spirit.

In the Kojiki‘s narrative of Kuniyuzuri (the transfer of the land), Amenokaku plays a crucial diplomatic role. When the sun goddess Amaterasu sought to negotiate with the earthly deities for control of Japan, she needed to reach Itsu-no-Ohabari, a deity who had blocked the heavenly river and made himself inaccessible. Only Amenokaku possessed the ability to traverse these supernatural barriers and deliver Amaterasu’s message.

The name Amenokaku contains multiple layers of meaning. While “Ame” indicates a heavenly or divine connection, “Kaku” has been interpreted various ways – as related to deer, to the act of striking with a sword, or to brilliance and radiance. Most significantly, scholars associate Amenokaku with the deer’s exceptional ability to leap across water and traverse difficult terrain, symbolically representing the capacity to cross between different worlds or states of being.

This boundary-crossing ability resonates strongly with the Shishigami Forest Spirit’s portrayal in Princess Mononoke mythology. The Forest Spirit walks on water, moves between life and death, and exists simultaneously as part of nature and beyond it. The film’s famous scene where grass instantly grows and withers beneath the Forest Spirit’s steps visualizes this liminal existence between creation and destruction, life and death.

Miyazaki’s Creative Synthesis

Hayao Miyazaki did not merely copy these traditional Japanese mythological creatures but creatively synthesized them into an entirely new mythological being. The Shishigami Forest Spirit combines the Kudan’s unsettling human-faced animal form, the Shinroku’s sacred status, and Amenokaku’s power to transcend boundaries, creating a deity that feels both ancient and contemporary.

Miyazaki’s creative process involved influences beyond Japanese mythology. He has acknowledged his admiration for manga artist Daijiro Morohoshi, whose works such as “Confucius Ankokuden” (Dark Tales of Confucius) and “Mad Men” feature mysterious beings that bear resemblance to both the Forest Spirit and its Nightwalker form. Additionally, Miyazaki stated that watching Falkor in “The NeverEnding Story” inspired his insight that “beings beyond human comprehension shouldn’t have human-like eyes,” leading to the Forest Spirit’s distinctive, otherworldly gaze.

This synthesis of diverse elements transformed the Shishigami Forest Spirit from a simple adaptation of traditional deities into a universal symbol that speaks to contemporary audiences worldwide while maintaining its roots in Japanese spiritual tradition.

The Cycle of Life and Death: Embodying Japanese Natural Philosophy

The Forest Spirit’s role as a deity governing both life and death reflects fundamental aspects of traditional Japanese philosophy regarding nature. Unlike Western dualistic thinking that often positions life and death as opposites, Japanese thought traditionally views them as interconnected aspects of a continuous cycle. This perspective, influenced by both Shinto and Buddhist philosophy, sees death not as an ending but as transformation within an eternal cycle of renewal.

In Princess Mononoke mythology, the Shishigami Forest Spirit demonstrates this principle through contradictory yet complementary actions. The deity heals Ashitaka’s curse while simultaneously draining life from anything it touches. The Forest Spirit itself exists within this cycle, described as being “born at the new moon and repeating birth and death with the moon’s phases.” This suggests that even divine beings participate in the natural cycle rather than standing outside it.

The film’s climactic scene, where the decapitated Forest Spirit transforms into a destructive force before ultimately restoring life to the devastated landscape, serves as a powerful metaphor for this cyclical worldview. The Japanese phrase “shi wa sei no hajimari” (death is the beginning of life) encapsulates this philosophy that the Forest Spirit embodies.

Contemporary Relevance and Universal Messages

More than 25 years after its release, Princess Mononoke and its enigmatic Shishigami Forest Spirit continue to pose crucial questions about humanity’s relationship with nature, the conflict between technological progress and traditional values, and the meaning of life itself. These themes resonate even more strongly in our current era of environmental crisis and technological disruption.

The human characters’ quest for the Forest Spirit’s head, believing it grants immortality, symbolizes humanity’s persistent desire to conquer death and dominate nature. This pursuit in Princess Mononoke mythology leads to catastrophic consequences, suggesting that some boundaries should not be crossed and some mysteries should remain unsolved. Yet the Forest Spirit’s final act – restoring life to the devastated forest before disappearing – offers hope for regeneration even after destruction.

Miyazaki’s genius lies in how he transformed specific Japanese mythological creatures into universal symbols. While the Kudan, Shinroku, and Amenokaku remain relatively unknown outside Japan, the Shishigami Forest Spirit has become a globally recognized icon representing nature’s power, mystery, and fragility. The film’s environmental message transcends cultural boundaries while maintaining its distinctly Japanese spiritual core.

The Legacy of Multiple Traditions

The richness of the Shishigami Forest Spirit comes from its multilayered heritage. Each contributing mythological source adds depth to the character:

From the Kudan, it inherits the unsettling power of the human-animal hybrid and the weight of prophetic knowledge about life and death. The Kudan tradition reminds us that some beings exist beyond human comprehension, serving as bridges between the mundane and supernatural worlds.

From the Shinroku tradition, it draws sacred authority and the role of nature’s guardian. Like the divine deer of Kasuga Shrine, the Forest Spirit commands reverence not through force but through its very existence as a link between the divine and natural worlds.

From Amenokaku, it gains the power to transcend boundaries – between water and land, earth and heaven, life and death. This boundary-crossing ability makes the Forest Spirit a liminal being, existing in the spaces between defined categories.

Conclusion: A Modern Myth from Ancient Roots

Hayao Miyazaki’s Shishigami Forest Spirit stands as a testament to the enduring power of mythological transformation. By drawing upon Japanese mythological creatures like the Kudan, Shinroku, and Amenokaku, Miyazaki created not just a character but a new myth for the modern age. The Forest Spirit embodies timeless questions about mortality, humanity’s relationship with nature, and the mysteries that lie beyond rational understanding.

In our contemporary world, where traditional beliefs often clash with scientific rationalism and where environmental destruction threatens our future, the Shishigami Forest Spirit offers a powerful reminder of what we lose when we attempt to dominate rather than coexist with nature. The creature’s final message in Princess Mononoke mythology – that life itself is indestructible even as individual forms pass away – provides both warning and hope for our species’ future relationship with the natural world.

For those encountering Princess Mononoke from outside Japanese culture, understanding these mythological roots enriches the viewing experience immeasurably. The Shishigami Forest Spirit emerges not as mere fantasy but as the crystallization of millennia of Japanese spiritual thought, transformed through artistic genius into a symbol that speaks to all humanity about our deepest fears and highest aspirations.

References

- Pixiv Encyclopedia: Shishigami

- Pixiv Encyclopedia: Kudan

- Pixiv Encyclopedia: Shinroku

- Pixiv Encyclopedia: Amenokaku

- Kokugakuin University Classic Culture Studies Divine Name Database

- Amenofuchikoma

- Ghibli Wiki

Editorial Notes:

- The featured images in this article were created using Midjourney, depicting scenes as envisioned by Zenchantique editorial staff based on the mythological descriptions discussed.

- Cultural artifacts and historical artwork shown are from public domain collections. Clicking on these images will direct you to their original source links.

- Should you identify any inaccuracies or errors in this article, please do not hesitate to contact us. We welcome corrections and additional insights from our readers.