If you’ve watched popular anime like Inuyasha, Jujutsu Kaisen, or Kekkaishi, you’ve likely encountered the mysterious concept of “kekkai” (結界) – sacred barriers that divide space with supernatural power, protecting against evil spirits and misfortune. This mystical concept isn’t mere fantasy; it’s deeply rooted in the foundations of Japanese culture.

Invisible Boundaries Creating Sacred Space

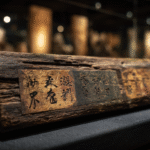

Anyone who has visited Shinto shrines in Japan has likely noticed the thick rope hanging at the entrance – the shimenawa (注連縄). Made from twisted rice straw, this rope appears simple and far from being a formidable defensive wall. Yet this seemingly fragile rope embodies the true essence of kekkai in Japanese culture.

Kekkai represents more than physical barriers. These sacred boundaries separate the sacred realm from the profane world through deeply spiritual demarcation. For the Japanese people, kekkai exists as an “invisible wall” within the heart and mind, deriving its power not from physical strength but from collective spiritual recognition. This understanding of sacred barriers reflects a unique aspect of Japanese culture that values spiritual significance over material fortification.

Kekkai as Preparation for Welcoming Deities

In traditional Japanese religious beliefs, deities (kami) were not permanent residents of any single location. They were understood as “yori-kitaru kami” – visiting deities who descended to the human realm at specific times. The kadomatsu (門松) pine decorations placed at house gates during New Year aren’t merely ornamental; they function as yorishiro (依り代) – physical objects that attract and provide temporary residence for the New Year deities.

Within this belief system of visiting deities, kekkai served as devices to create special spaces for welcoming the kami. By stretching shimenawa ropes around an area, ordinary profane space temporarily transforms into a sacred realm. This transformation represents the most crucial function of kekkai in Japanese culture – the ability to sanctify everyday spaces through ritual demarcation.

Japan’s Unique Spatial Recognition Emphasizing Spirituality

Unlike Western castles with their massive walls and fortresses, Japanese kekkai effectively fulfills its role through shimenawa swaying in the wind or thin curtains. This reflects how Japanese culture has historically prioritized spiritual meaning over material strength. The sumo wrestling ring (dohyō), the water basin (tsukubai) in tea ceremony gardens – all represent forms of kekkai, embodying the Japanese aesthetic that reveres “ma” (間) or negative space.

Particularly fascinating is the culture of “mitate” (見立て) associated with kekkai. The sacred groves (chinju no mori) recreating mountain forests within cities, the kadomatsu inviting mountain deities, the tea house as “a mountain dwelling within the city” (shinaka no sankyo) – all exemplify this uniquely Japanese spiritual practice of “seeing as” or symbolic representation of sacred spaces within everyday life. These practices at Shinto shrines demonstrate how Japanese culture seamlessly integrates the sacred into the mundane.

The Essence of Kekkai: Where Time and Space Interweave

Understanding kekkai requires recognizing it as more than merely a spatial concept. Originally, these sacred barriers were established only during specific periods for festivals or religious ceremonies, then dismantled afterward. Thus, kekkai represented an inherently dynamic concept existing at the intersection of time and space.

However, kekkai evolved over time. What were once temporary sacred spaces became fixed in permanent structures like Shinto shrine buildings. Yet the Japanese conception of kekkai never completely disappeared. The fact that the same Shinto shrines display entirely different atmospheres on festival days versus ordinary days proves this ancient understanding of sacred barriers continues to thrive. This temporal aspect of kekkai in Japanese culture distinguishes it from static Western concepts of sacred space.

Purifying Oneself to Cross the Boundary

Crossing kekkai into sacred space requires more than mere physical movement. The water basins (chōzuya 手水舎) at Shinto shrine entrances serve for minimal purification rituals – washing hands and rinsing the mouth signifies cleansing worldly impurities before entering sacred grounds. This practice, known as misogi in its fuller form, represents a fundamental aspect of how kekkai functions in Japanese culture.

Historically, festival participants underwent more intensive purification. They practiced “kori” (垢離) – standing under waterfalls or immersing themselves in seawater to cleanse body and spirit. Some scholars suggest Japan’s famous bathing culture originated from these purification practices associated with crossing sacred barriers. The act of cleansing itself became a spiritual preparation for transcending the invisible kekkai separating the profane from the sacred.

Multiple Layers of Sacred Boundaries

Kekkai in Japanese culture rarely exists as a single barrier. Many Shinto shrines feature multiple torii gates – the “first torii” (ichi no torii), “second torii” (ni no torii), and “third torii” (san no torii). This arrangement indicates graduated levels of sanctity along the path from the profane world to the sacred center.

Worshippers passing through each successive kekkai gradually shed their worldly nature, elevating themselves to a state of purity appropriate for encountering the divine. This layered structure of sacred barriers eloquently expresses the nuanced Japanese spiritual sensibility. Rather than a stark division between sacred and profane, Japanese culture recognizes transitional spaces of increasing holiness.

Kekkai also manifests through points rather than lines. The circular shimenawa (wa-jime) decorating entrances at New Year, or sakaki branches placed at village boundaries, demonstrate how single points can sanctify broad areas. The holly leaves (hiiragi) displayed during Setsubun (the day before spring) and iris leaves (shōbu) during Boys’ Day likewise function as kekkai protecting against malevolent influences. These examples from Shinto shrines and folk practices illustrate the flexibility of sacred barriers in Japanese culture.

Enclosed Sacred Spaces

Sometimes kekkai required complete enclosure. The custom of “toshigomo” involved hanging new straw mats inside homes at New Year, while children constructed temporary huts for New Year or Bon Festival observances. The snow houses called kamakura serve similar purposes – Wikipedia notes these originated in Akita Prefecture as ritual spaces for water deity worship.

Within these sealed spaces, humans spent defined periods in communion with deities, gaining renewed life force. By secluding themselves in darkness, participants achieved complete separation from the mundane world, experiencing sacred time in its purest form. This practice of ritual seclusion demonstrates how kekkai in Japanese culture creates not just spatial but temporal sacred boundaries.

Kekkai’s Special Function in Medieval Japan

Intriguingly, during Japan’s medieval period, kekkai served as “asylums” (sanctuaries) beyond governmental authority. Festival grounds became temporary spaces where social hierarchies inverted and normal restrictions lifted. This aspect of sacred barriers reveals their role in Japanese culture as spaces of transformation and liberation.

The performing art called dengaku particularly embodied this transformative violence, often inciting mass hysteria and sometimes actual riots. The Great Dengaku of 1096 (Eichō era) exemplifies how kekkai spaces permitted normally forbidden behaviors. Sacred barriers didn’t merely separate holy from profane; they created special zones where everyday norms could be suspended or challenged. This historical function of kekkai at Shinto shrines and festival grounds added layers of social meaning beyond purely religious significance.

The Spirit of Kekkai in Modern Times

While shrine architecture fixed formerly temporary kekkai into permanent structures, the Japanese conception of sacred barriers evolved rather than disappeared. In Japanese homes, sliding doors (fusuma), paper screens (shōji), and curtain dividers (noren) function as devices to flexibly partition space and transform its character – a domestic application of kekkai principles.

The subtle arrangements in tea ceremony rooms, the symbolic props on Noh theater stages, and contemporary festival decorations at Shinto shrines – all perpetuate the spirit of sanctifying space according to time and circumstance. Through these evolving forms, Japanese culture maintains its ancient understanding of kekkai as dynamic rather than static boundaries.

What Kekkai Teaches Us About Japanese Culture’s Essence

The kekkai appearing in anime and manga represent far more than fantasy constructs. They visualize the spiritual boundaries flowing through the depths of Japanese culture – demarcations between sacred and profane, inside and outside, pure and impure. These sacred barriers embody a worldview fundamentally different from Western conceptions of space and protection.

Prioritizing spiritual significance over physical strength, perceiving space as fluid rather than fixed, and above all, determining effectiveness through collective states of mind – this is the essence of Japan’s kekkai culture. This unique spatial recognition reflects the Japanese worldview itself, which values harmony with nature and maintains reverence for the invisible. The shimenawa at Shinto shrines perfectly exemplifies this principle: a simple rope becomes an impenetrable barrier through shared belief rather than material fortification.

Consider how this contrasts with Western sacred architecture. While European cathedrals inspire awe through massive stone walls and soaring spires, Japanese sacred spaces achieve sanctity through minimal gestures – a shimenawa rope, a torii gate, or even just a single sakaki branch. This difference illuminates fundamentally different approaches to the sacred. Where Western traditions often emphasize permanent, monumental structures separating human from divine, Japanese culture creates permeable, temporary boundaries that allow for fluid interaction between the sacred and profane realms.

The concept of kekkai also reveals Japanese culture’s sophisticated understanding of liminality – the transitional spaces between states of being. Rather than sharp divisions, kekkai creates gradual transitions, acknowledging that transformation from profane to sacred requires process, not instantaneous change. This nuanced approach appears throughout Japanese culture, from the multiple gates at Shinto shrines to the careful choreography of tea ceremony, where each movement marks progression toward a heightened spiritual state.

Living Tradition in Contemporary Japan

Today’s Japan continues to manifest kekkai principles in unexpected ways. Modern architecture incorporates traditional concepts of flexible space division. Corporate offices use moveable partitions echoing the adaptability of fusuma. Even convenience stores place shimenawa across their entrances at New Year, temporarily transforming commercial spaces into sites for seasonal blessing. These contemporary applications demonstrate how deeply kekkai concepts permeate Japanese culture beyond explicitly religious contexts.

The digital age brings new interpretations of sacred barriers. Virtual Shinto shrines offer online omamori (protective charms), creating digital kekkai for the internet age. Popular games and anime don’t merely use kekkai as plot devices but explore their philosophical implications, questioning boundaries between real and virtual, human and supernatural. This ongoing cultural dialogue ensures kekkai remains relevant to each generation while maintaining connection to ancient principles.

Understanding Japan Through Its Sacred Boundaries

For visitors to Japan, recognizing kekkai transforms the travel experience. That shimenawa wrapped around an ancient tree isn’t merely decorative – it marks the tree as sacred, a dwelling place for kami. The stone markers along pilgrimage routes create invisible corridors of sanctity across the landscape. Even the white gravel in Shinto shrine courtyards functions as kekkai, its pristine surface demarcating pure ground from the ordinary earth beyond.

This awareness extends beyond religious sites. The noren hanging in restaurant doorways, the carefully maintained boundaries of private gardens, even the ritual of removing shoes when entering homes – all echo kekkai principles of marking transitions between different spatial qualities. Understanding these sacred barriers offers profound insight into how Japanese culture organizes both physical and social space.

When you next visit Japan, pay attention to the shimenawa at Shinto shrines, the multiple torii gates, and the various invisible boundaries inscribed throughout the landscape. Within these seemingly simple markers lies a doorway to the Japanese spiritual world, preserved and transmitted across more than a millennium. The kekkai surrounding Japan’s sacred spaces don’t merely separate – they invite those who understand their language to cross into a realm where the material and spiritual intertwine, where ancient wisdom continues to shape contemporary life.

Through understanding kekkai, we glimpse the heart of Japanese culture: a world where boundaries exist not to exclude but to create spaces of transformation, where the sacred emerges through collective recognition rather than imposed authority, and where the most powerful barriers are often the most ethereal. In this lies a profound lesson for our interconnected yet divided world – that the most meaningful boundaries are those we carry within ourselves, made manifest through shared understanding and mutual respect.

Reference

- Nihon no Bi to Bunka : Art japanesque 11 [Japanese Beauty and Culture: Art japanesque 11]. Tokyo: Kodansha, 1983.

- Wikipedia Japan 「Kekkai」

Notes and Disclaimers

- The photographic images in this article were created using Midjourney AI, depicting scenes as envisioned by Zenchantique’s editorial team to illustrate the concepts discussed.

- Cultural artifacts and historical paintings featured are in the Public Domain. Clicking on these images will direct you to their original source links.

- The concept of kekkai has been studied from various perspectives including anthropology, architecture, and cultural studies. This article approaches the subject primarily from architectural and cultural viewpoints, which may differ from materials written from purely religious or Buddhist doctrinal perspectives.

- We strive for accuracy in presenting Japanese cultural concepts. If you notice any errors or misrepresentations, please contact us so we can make appropriate corrections.