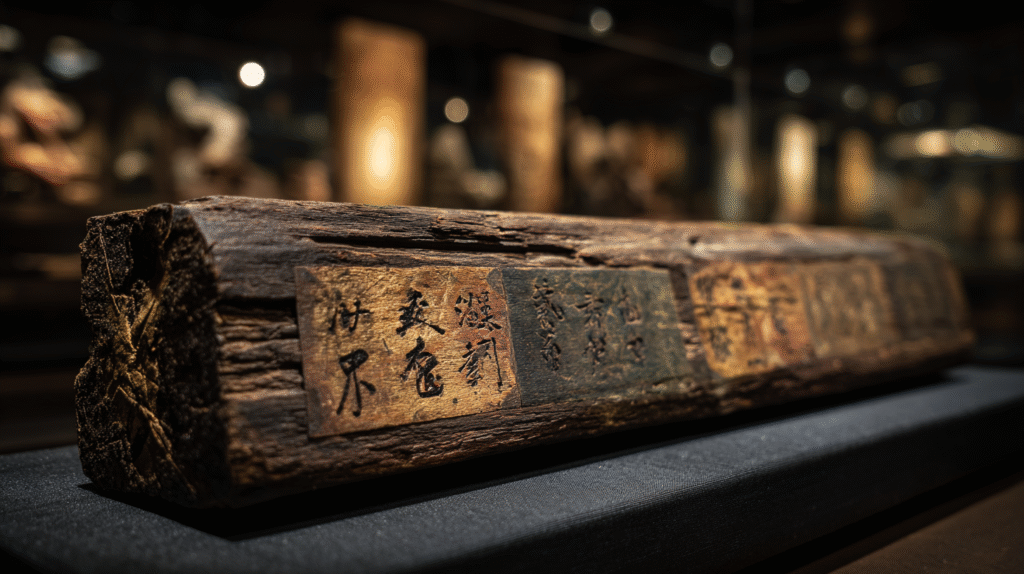

In the ancent city of Nara, within the hallowed halls of Todai-ji temple’s Shosoin repository, lies a piece of wood that has captivated Japan’s most powerful leaders for over a millennium. Known as Ranjatai (蘭奢待), this legendary incense wood represents one of the most treasured artifacts in Japanese cultural history, embodying the nation’s sophisticated aesthetic sensibilities and its profound relationship with fragrance.

Recent scientific analysis conducted by the Imperial Household Agency’s Shosoin office in July 2025 has unveiled new insights into this mystical aromatic wood. Researchers detected over 300 fragrance components, including labdanum—a sweet, honey and cinnamon-like scent that defines Ranjatai’s distinctive aroma. Additionally, radiocarbon dating revealed that the original tree was felled between the late 8th and late 9th centuries, adding another layer to its already rich history.

The Path to Becoming Japan’s Premier Incense

Ranjatai, officially catalogued as “Ojukuko” (黄熟香) or “yellow ripe incense,” is an impressive specimen measuring 156 centimeters in length, with a maximum diameter of 42.5 centimeters and weighing 11.6 kilograms. This precious incense wood belongs to the highest grade of agarwood (aloeswood), derived from Aquilaria trees of the Thymelaeaceae family native to Southeast Asia.

Agarwood forms when these trees become infected with a specific type of mold, triggering the production of a dark, resinous heartwood as a defense mechanism. This resin-saturated wood releases its distinctive fragrance when heated, making it one of the most valuable aromatic substances in the world. The finest quality agarwood, dense enough to sink in water due to its high resin content, is known in Japan as “kyara” (伽羅), and Ranjatai represents this supreme grade.

Interestingly, much of the wood appears deteriorated or hollow, resembling decayed timber. However, experts explain this is not due to age but rather intentional carving. Ancient craftsmen deliberately removed portions lacking aromatic compounds to prevent unwanted scents during burning—a practice that continues with premium incense woods today. This meticulous attention to detail reflects the sophisticated understanding of incense preparation that existed over a thousand years ago.

The name “Ranjatai” itself carries hidden significance. Within its three characters (蘭奢待) are concealed the three characters of Todai-ji (東大寺), the temple that houses it. This clever wordplay emerged during the Muromachi period (1336-1573), though the exact originator remains unknown. The name thus serves as both an identifier and a cryptic reference to its home, demonstrating the Japanese penchant for layered meanings and subtle references.

The Fragrance That Enchanted Power

Throughout Japanese history, Ranjatai has been intimately connected with the nation’s most influential figures. The Ashikaga shoguns of the Muromachi period, the warlord Oda Nobunaga, and Emperor Meiji all sought to possess even a small fragment of this legendary incense wood. But what drove these powerful leaders to covet a piece of aromatic wood so intensely?

The tradition began with Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, who in 1385 became the first recorded shogun to cut a piece from Ranjatai after viewing the Shosoin treasures following his ordination ceremony at Todai-ji. This established a precedent followed by subsequent Ashikaga shoguns. Yoshinori continued the practice, and Yoshimasa, in 1465, cut two one-inch square pieces—presenting one to Emperor Go-Tsuchimikado and keeping one for himself, while also gifting a smaller piece to Todai-ji’s head priest. This distribution demonstrated not just power but also political acumen and cultural sophistication.

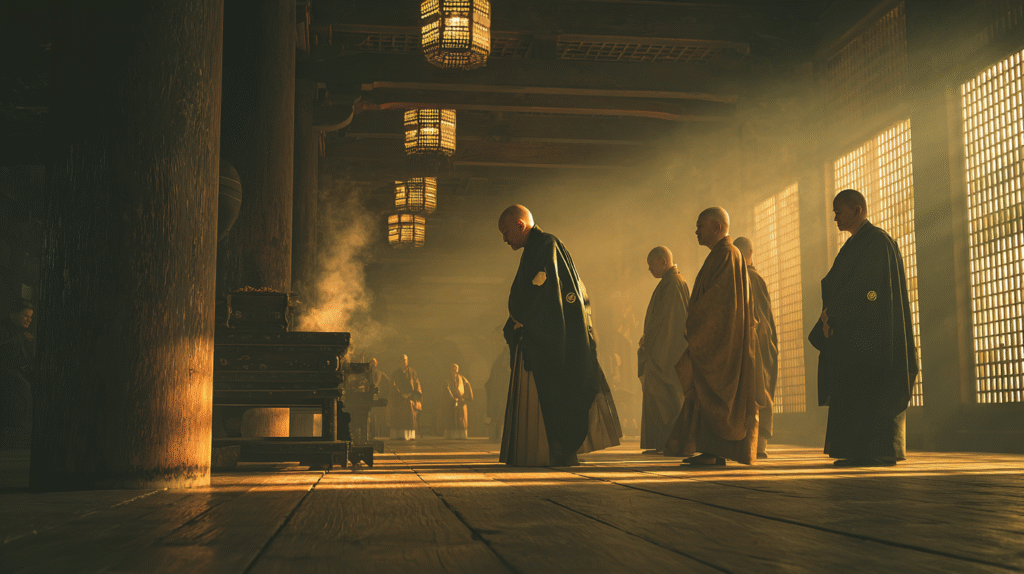

Oda Nobunaga’s acquisition of Ranjatai in 1574 represents one of the most documented instances of this sacred wood’s cutting. Contrary to popular narratives that paint Nobunaga as forcefully seizing the treasure, recent historical research reveals a more nuanced picture. Nobunaga followed proper protocols, obtaining imperial permission from Emperor Ogimachi before approaching Todai-ji. On March 28, 1574, under the supervision of imperial envoys and three monks from Todai-ji, master craftsmen carefully cut two pieces from Ranjatai using a special saw.

Nobunaga’s subsequent actions reveal his understanding of Ranjatai’s cultural significance. He presented one piece to Emperor Ogimachi and retained the other. On April 3, he hosted an elaborate tea ceremony in Kyoto, where he gifted fragments of Ranjatai to the era’s most renowned tea masters, including Sen no Rikyu (then known as Sen Sōeki) and Tsuda Sōgyū. This gesture transcended mere display of power—it demonstrated Nobunaga’s appreciation for cultural refinement and his desire to share this treasure with those who could truly appreciate its value.

Japanese Aesthetic of Fragrance

To understand why Ranjatai holds such significance in Japanese culture, one must explore Japan’s unique relationship with fragrance. Unlike Western perfume traditions that often emphasize bold, persistent scents, Japanese incense culture values subtlety, complexity, and the ephemeral nature of aroma. This philosophical approach to fragrance reflects broader Japanese aesthetic principles such as mono no aware (the pathos of things) and wabi-sabi (finding beauty in imperfection and impermanence).

During the Heian period (794-1185), the golden age of Japanese court culture, aristocrats engaged in sophisticated incense competitions called “takimono-awase,” where participants would blend and judge various aromatic combinations. The Tale of Genji, Japan’s classic 11th-century novel, contains numerous references to characters being identified by their signature scents, demonstrating how fragrance was integral to personal identity and social refinement.

Ranjatai’s fragrance is traditionally described as “furumeki-shizuka”—a term that defies simple translation. It suggests something ancient yet serene, carrying the weight of time without heaviness, maintaining a pure, noble quality. The recent identification of labdanum among its 300+ aromatic compounds helps explain this complex character. These components create a harmonious blend that has captivated Japanese sensibilities for centuries.

The Japanese approach to appreciating incense, known as kōdō (the Way of Fragrance), elevates scent appreciation to a spiritual practice alongside tea ceremony and flower arrangement. Practitioners “listen” to incense rather than simply smell it, emphasizing the meditative, almost synesthetic experience of engaging with fragrance. Ranjatai, as the ultimate expression of this art form, represents not just a pleasant aroma but a gateway to transcendent experience.

Millennium of Preservation and Power

The preservation of Ranjatai within the Shosoin repository represents a remarkable feat of cultural continuity. The Shosoin itself is an architectural marvel—a raised-floor wooden storehouse built in the azekura style, which naturally regulates temperature and humidity without modern climate control. Originally constructed to house Emperor Shomu’s belongings after his death in 756, it was dedicated to Todai-ji by Empress Komyo. This repository has protected Ranjatai and thousands of other treasures through wars, natural disasters, and the passage of centuries.

The exact circumstances of how Ranjatai arrived at the Shosoin remain shrouded in mystery. While it was long believed to have been presented during the Great Buddha’s eye-opening ceremony at Todai-ji in 752, the recent radiocarbon dating revealing its felling between 772-885 CE has disproven this theory. Some scholars suggest it arrived during the early Heian period, possibly brought by diplomatic missions from Tang China or Southeast Asian kingdoms. Others propose it was transferred from another temple repository in 1116 when aging storehouses were consolidated.

What is documented with certainty are the marks left by those who claimed pieces of this precious wood. A 1997 study identified 38 cutting marks on Ranjatai, with evidence suggesting approximately 50 extractions over the centuries. Today, three cuts bear labels reading “Place where Ashikaga Yoshimasa received,” “Place where Oda Nobunaga received,” and “Cut by imperial command in Meiji 10 (1877).” These labels, added during the Meiji period, serve as a physical record of power and cultural authority in Japan.

The story of who didn’t cut Ranjatai is equally telling. Tokugawa Ieyasu, founder of the Tokugawa shogunate that ruled Japan for over 250 years, inspected the Shosoin treasures in 1602 but refrained from taking any incense. Historical records indicate he believed cutting the sacred wood would bring misfortune—a decision that reveals how even Japan’s most powerful military leader respected the spiritual and cultural weight of Ranjatai.

Emperor Meiji’s extraction in 1877 marked the last recorded cutting of Ranjatai. According to the Meiji Tenno Ki (Record of Emperor Meiji), he commanded the removal of a piece measuring 2 sun (approximately 6 centimeters) and weighing 8.9 grams during his visit to Nara. The emperor then participated in a formal incense ceremony at Todai-ji’s Tonan-in hall, where the imperial record notes that “the fragrant smoke filled the temporary palace with its aroma.” This ceremonial appreciation of Ranjatai connected the modernizing Meiji era with ancient traditions.

Living Heritage in the Modern World

In contemporary Japan, Ranjatai continues to captivate public imagination while remaining largely inaccessible. The Shosoin opens its doors only once a year for airing and inspection, and Ranjatai is displayed publicly only on rare occasions. Its appearances at the Shosoin exhibitions in 1997, 2011, and most recently in 2019 to commemorate Emperor Naruhito’s enthronement drew massive crowds, with visitors waiting hours for a brief glimpse of this legendary incense wood through protective glass.

The 2025 scientific analysis that identified Ranjatai’s aromatic components represents a fascinating intersection of ancient culture and modern technology. Working with Takasago International Corporation, researchers analyzed microscopic fragments—pieces just one millimeter wide—to decode the chemical signature of this thousand-year-old fragrance. This collaboration between the Shosoin office and private industry demonstrates how Japanese incense culture continues to evolve while maintaining deep respect for tradition.

Even more exciting for the public is the upcoming immersive exhibition traveling from the Osaka Museum of History to Tokyo’s Ueno Royal Museum from June to November 2025. For the first time, visitors will be able to experience a scientifically reconstructed version of Ranjatai’s fragrance. Using the data from the chemical analysis, perfumers have created an approximation of the scent that captivated Oda Nobunaga and generations of Japanese leaders. While no reproduction can fully capture the complexity of the original, this initiative makes the intangible heritage of Japanese incense culture accessible to contemporary audiences.

The enduring fascination with Ranjatai reflects deeper aspects of Japanese cultural values. In an era of mass production and disposability, this single piece of wood—irreplaceable and finite—embodies principles of mottainai (regret over waste) and the Buddhist concept of impermanence. Each cutting throughout history diminished the original while paradoxically increasing its mystique and cultural significance.

The Essence of Japanese Aesthetics

The cultural significance of Ranjatai extends far beyond its material value as rare incense wood. It embodies fundamental concepts in Japanese aesthetics and philosophy that foreign observers often find difficult to grasp. The Japanese term “yūgen” (幽玄)—suggesting subtle profundity and mysterious beauty—perfectly captures what Ranjatai represents. This aesthetic principle values what is suggested rather than explicitly stated, what is felt rather than seen.

In Japanese incense culture, the appreciation of fragrance involves all the senses and engages the imagination. Practitioners of kōdō speak of “listening” to incense, a translation of the Japanese term “mon-kō” (聞香). This terminology reveals how the Japanese approach transforms a simple sensory experience into a meditative practice. When one “listens” to Ranjatai, one engages not just with its physical aroma but with its history, the countless individuals who have experienced it, and the cultural continuity it represents.

The rarity and finite nature of Ranjatai also exemplifies the Japanese aesthetic concept of “ichi-go ichi-e” (一期一会)—the idea that each encounter is unique and will never be repeated. Every time Ranjatai has been burned throughout history represented an irreplaceable moment. This philosophical approach stands in stark contrast to Western perfumery’s emphasis on consistent reproduction and widespread availability. The very irreproducibility of Ranjatai enhances its value in Japanese culture.

Furthermore, Ranjatai serves as a tangible link to Japan’s cultural golden ages. When Oda Nobunaga held his fragment of this sacred incense in 1574, he was connecting himself to the Heian court culture that produced The Tale of Genji, to the aesthetic refinement of the Ashikaga shoguns, and to the Buddhist traditions that brought incense culture to Japan. This temporal continuity—the ability to experience the same fragrance that inspired historical figures centuries ago—provides a sensory bridge across time that few other artifacts can match.

Preserving Intangible Heritage

The story of Ranjatai raises important questions about cultural preservation in the 21st century. How do we maintain traditions centered on ephemeral experiences like fragrance? How do we balance preservation with access, ensuring future generations can appreciate these treasures while protecting them from depletion?

The Shosoin’s approach offers one model. By strictly limiting access and maintaining meticulous records, they have preserved Ranjatai for over a millennium. The recent scientific analysis represents a new chapter in this preservation effort. By documenting the molecular composition of Ranjatai’s fragrance, researchers have created a kind of olfactory backup—ensuring that even if the physical wood eventually depletes, future generations will have data to understand what made this incense so special.

Japanese incense houses, some operating continuously for over 400 years, play a crucial role in maintaining this cultural tradition. Companies like Shoyeido, Nippon Kodo, and Baieido continue to produce high-quality incense using traditional methods while adapting to contemporary lifestyles. They serve as living repositories of knowledge about aromatic woods, blending techniques, and the cultural protocols surrounding incense appreciation.

The international interest in Japanese incense culture has grown significantly in recent years, partly due to increased global attention to mindfulness practices and sensory experiences. Ranjatai, as the ultimate expression of Japanese incense culture, has become a symbol of Japan’s sophisticated approach to intangible cultural heritage. Museums worldwide now include Japanese incense in their collections, and workshops on kōdō attract participants eager to understand this subtle art form.

Conclusion: The Eternal Fragrance

As we stand in the 21st century, Ranjatai continues to occupy a unique position in Japanese culture. It remains physically present in the Shosoin, bearing the marks of historical figures like Oda Nobunaga who sought to possess even a small piece of its essence. Yet it also exists in the realm of memory and imagination, its fragrance known directly to only a select few throughout history.

The latest scientific revelations about Ranjatai—its complex aromatic profile centered on labdanum, its origins in 8th or 9th century Southeast Asia—add new dimensions to our understanding without diminishing its mystery. If anything, learning that this wood contains over 300 distinct aromatic compounds only deepens our appreciation for the sophisticated palates of those who recognized its extraordinary nature centuries ago.

Ranjatai teaches us that true luxury isn’t about ostentation or accessibility but about depth, complexity, and connection to something greater than ourselves. In an age of instant gratification and disposable goods, this ancient incense wood reminds us of the value of patience, preservation, and the profound experiences that come from engaging with irreplaceable cultural treasures.

The fragrance that captivated Oda Nobunaga and countless others across the centuries continues to represent the pinnacle of Japanese aesthetic achievement. Though few will ever experience its actual scent, Ranjatai’s true gift to humanity may be the cultural values it embodies: the pursuit of refined beauty, respect for tradition, and the understanding that some things become more precious precisely because they cannot be reproduced or replaced.

As the Shosoin continues its millennial duty of preservation, and as modern science unlocks new ways to understand and share Ranjatai’s essence, this legendary incense wood remains what it has always been—a bridge between past and present, a teacher of impermanence and beauty, and Japan’s most treasured fragrance. In its silence and stillness, Ranjatai continues to speak volumes about what humans can achieve when they dedicate themselves to preserving and appreciating the finest expressions of culture and art.

References

- NHK News: Shosoin Treasure: Fragrance Components of “Ranjatai” Incense Wood Sought by Oda Nobunaga Revealed

- Wikipedia Japan: Ranjatai

- Wikipedia: Ranjatai (wood)

- Shōsōin no Hōmotsu (Treasures of the Shōsōin), Modern Education Library Edition, edited by Yuzuru Okada, Social Thought Research Publishing, 1959, p.104

- Introduction to Shōsōin Research, edited by Yoshisuke Iida, Tokushima City Terashima Elementary School, 1937, pp.45-49

Editorial Notes:

- The photographic images accompanying this article were created using Midjourney, depicting scenes as envisioned by Zenchantique’s editorial team to illustrate the historical and cultural contexts discussed.

- In translating historical documents and archaic Japanese terminology, we have utilized AI-assisted translation tools for reference. Given the complexity of classical Japanese language and historical texts, we welcome any corrections or clarifications from our readers. Please feel free to contact us if you identify any inaccuracies or have additional insights to share.