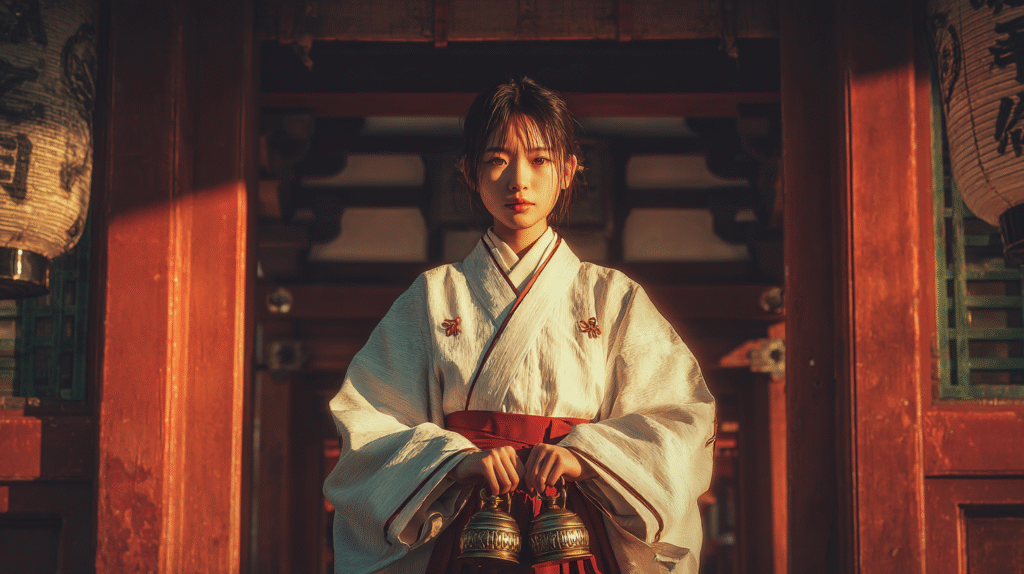

When visiting a Shinto shrine in Japan, you may encounter young women dressed in distinctive red and white garments. These are miko priestesses, sacred intermediaries between the divine and human realms who have played crucial roles in Japanese religious culture from ancient times to the present. To understand the origins of the miko priestess tradition, we must trace back to the story of one particular deity: Ame-no-Uzume-no-Mikoto, recognized as the first miko priestess in Japanese mythology and still revered today as the Japanese goddess of performing arts and dawn.

Understanding Miko: Sacred Mediators Between Gods and Humans

To comprehend what a miko priestess truly represents, we must first understand the relationship between kami (Shinto deities) and humans in Japanese religious thought. In Shintoism, the indigenous religion of Japan, deities are not distant beings separated from the human world. Rather, they inhabit all aspects of nature, occasionally manifesting before people and responding to their prayers as accessible, intimate presences.

The miko priestess possesses special abilities that enable communication between these divine beings and humanity. The Chinese character “miko” (巫女) combines elements meaning “shaman” and “woman,” originating from pictographs representing females who communicate with spirits. In ancient times, miko priestesses would enter states of divine possession (kamigakari), allowing them to hear the voices of the kami and convey divine will to their communities. This practice served not merely as religious ritual but as an essential means for communal decision-making and problem-solving.

Modern miko priestesses at contemporary shrines inherit this ancient tradition, though their roles have evolved significantly. They perform kagura (sacred dances) before the kami, distribute omamori (protective amulets), guide visitors, and handle various practical duties. Yet beneath these contemporary functions, the essential nature of standing at the boundary between the sacred and profane continues to define the miko priestess identity.

Ame-no-Uzume: The Japanese Goddess Who Saved the World Through Laughter and Dance

In Japanese mythology, the deity recognized as the originator of the miko priestess tradition is Ame-no-Uzume-no-Mikoto. Her name “Uzume” has multiple interpretations: it may mean “woman with hair ornaments” (as suggested by the character 鈿 meaning hairpin) or “strong woman” (Ozume). This Japanese goddess is most famous for her role in the myth of the “Cave of Heaven” (Ama-no-Iwato), where she enticed the sun goddess Amaterasu-Omikami from her hiding place.

The story unfolds thus: Frightened by the violent behavior of her brother Susanoo, the storm god, Amaterasu retreated into a celestial cave called Ama-no-Iwato. As the sun goddess disappeared, the world plunged into darkness, and calamities began occurring everywhere. The desperate deities gathered at the heavenly river Ame-no-Yasukawa, where Omoikane, the god of wisdom, proposed holding a festive celebration outside the cave.

This is where Ame-no-Uzume made her legendary appearance. Standing atop an overturned tub (uke), she began dancing while stamping her feet rhythmically. According to the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters, Japan’s oldest chronicle), she “exposed her breasts and pushed her skirt-band down to her genitals.” In other words, this Japanese goddess performed an extremely provocative and erotic dance, baring her chest and lowering her garment to reveal her private parts.

This unexpected spectacle caused the assembled eight million deities to burst into uproarious laughter. The laughter was so loud that Amaterasu, curious about the commotion, cracked open the cave door to peek outside. Ame-no-Uzume then declared, “A deity more noble than you has appeared!” while showing Amaterasu her own radiant reflection in a prepared mirror. As Amaterasu leaned forward to see her brilliant image more clearly, the strength god Tajikarao pulled her out, and light returned to the world.

From Shamanism to Performing Arts: The Birth of Kagura

The dance of Ame-no-Uzume represents more than a mere mythological episode. It reflects the mythologization of ancient Japanese shamanic practices while simultaneously marking the origin of Japanese performing arts. This connection between religious ritual and entertainment remains fundamental to understanding Japanese culture.

The folklorist Orikuchi Shinobu interpreted Ame-no-Uzume’s dance as a form of “tamashizume” (soul-pacification ritual). In ancient times, souls were believed to easily separate from bodies, making rituals to keep the souls of emperors and nobles anchored to their physical forms critically important. The intense dance performed by this Japanese goddess was precisely this type of ritual magic, a shamanic technique to recall Amaterasu’s soul.

This mythical dance later became systematized as “kagura,” literally meaning “entertainment for the kami.” Kagura continues to be performed at shrines throughout Japan today. Notably, many kagura repertoires include reenactments of Ame-no-Uzume’s cave-opening dance, with “Iwato-biraki” (Opening the Rock Cave) serving as a central piece in regional kagura traditions.

Contemporary miko priestesses, as successors to Ame-no-Uzume, perform dances before the kami. While their movements have become refined and stylized, the underlying spirit of “laughing and dancing with the gods” that Ame-no-Uzume demonstrated continues to animate their practice. The miko priestess costume of white chihaya (ceremonial robe) and scarlet hakama (divided skirt) visually represents both purity and vitality, symbolizing their position at the boundary between sacred and profane realms.

The Multifaceted Nature of Ame-no-Uzume: From Performance Deity to Goddess of Fortune

Following the cave incident, Ame-no-Uzume continued to play significant roles in Japanese mythology. During the Tenson Kōrin (Descent of the Heavenly Grandson), she accompanied Ninigi-no-Mikoto, Amaterasu’s grandson, on his journey to earth. When the god Sarutahiko blocked their path at the floating bridge of heaven, this Japanese goddess was chosen to negotiate with him. The texts describe how she again bared her breasts and adopted a provocative stance when confronting Sarutahiko, employing the same bold tactics that had proven successful at the heavenly cave.

However, this encounter evolved from confrontation to connection. According to some versions, Ame-no-Uzume married Sarutahiko, becoming the ancestress of the Sarume clan (猿女君). This narrative symbolizes the harmonious union between the Amatsukami (heavenly deities) and Kunitsukami (earthly deities), while demonstrating the miko priestess role as mediator between different realms.

Another intriguing episode involves Ame-no-Uzume gathering sea creatures to pledge allegiance to Ninigi-no-Mikoto. When all creatures answered “we will serve” except the sea cucumber, which remained silent, the Japanese goddess angrily slit its mouth with a small knife. This is why, the myth explains, sea cucumbers have split mouths to this day. While seemingly cruel, this story illustrates another aspect of the miko priestess function: serving as divine judge and enforcer of cosmic order.

In contemporary Japan, Ame-no-Uzume is venerated in various forms. Beyond her role as patron of performing arts, she is beloved as “Okame” or “Otafuku,” names associated with good fortune and happiness. Her expressive face and cheerful disposition became the prototype for Japanese aesthetic concepts of “aikyo” (charm) and “fukufukushisa” (plump prosperity), representing joy and abundance in Japanese culture.

Global Perspectives: Female Shamans Across Cultures

Viewing Ame-no-Uzume and the miko priestess tradition from a global perspective reveals fascinating parallels. French medieval literature scholar Philippe Walter has noted similarities between this Japanese goddess and the Celtic figure known as Sheela na gig. Like Ame-no-Uzume, Sheela na gig displays explicit sexuality to demonstrate powers of creation and destruction.

This reverence for women’s sacred power appears in shamanic traditions worldwide. From Siberian shamans to African female ritualists and South American women healers, many cultures recognize women as possessing special abilities to bridge spiritual and material worlds. This universal phenomenon likely stems from widespread awe regarding women’s life-giving powers and intuitive perceptual abilities.

The miko priestess tradition shares elements with other female religious specialists globally. Like the Oracle at Delphi in ancient Greece or the Vestal Virgins of Rome, miko priestesses maintained ritual purity while serving as conduits for divine communication. However, the Japanese tradition uniquely emphasizes the integration of performance, beauty, and spiritual power, reflecting distinctive aspects of Japanese religious aesthetics.

Modern Miko Priestesses: Living Traditions

Today’s miko priestesses serving at Japanese shrines are direct spiritual descendants of Ame-no-Uzume. Most are unmarried women in their late teens or twenties who embody Japanese traditional culture through their shrine service. During major occasions like New Year’s hatsumode (first shrine visit), Shichi-Go-San (children’s blessing ceremony), and wedding ceremonies, these miko priestesses play vital roles in connecting worshippers with the kami.

Particularly noteworthy is the tradition of miko-mai (shrine maiden dance). Watching a miko priestess gracefully dance with bells or fans might seem far removed from Ame-no-Uzume’s wild, provocative performance. Yet at their essence, both share the same purpose: facilitating communion with the divine through dance and bringing sacred experiences to participants.

Modern miko priestesses face contemporary challenges. The traditional restriction of the role to young, unmarried women has become a subject of debate from gender equality perspectives. However, this tradition is deeply intertwined with religious concepts of “purity” and “innocence,” making change complex and controversial. Some shrines have begun employing older women or married women in auxiliary roles, suggesting gradual evolution in the tradition.

The training of miko priestesses today combines ancient practices with modern requirements. They learn traditional dances, proper shrine etiquette, and calligraphy, while also developing skills in customer service and administrative tasks. This blend of sacred and practical duties reflects how the miko priestess role has adapted to contemporary society while maintaining its spiritual core.

The Eternal Sacred Women: A Continuing Legacy

The tradition of miko priestesses originating with Ame-no-Uzume represents far more than religious custom. It embodies the essence of Japanese culture in bridging seemingly opposite elements: human and divine, material and spiritual, reason and intuition, solemnity and laughter, sacred and profane. This Japanese goddess teaches that even the most desperate situations can be transformed through laughter, creativity, and life force.

Ame-no-Uzume’s bold dance before the heavenly cave demonstrates wisdom in overcoming despair through joy and vitality. Her existence symbolizes women’s creative power and flexibility in transcending difficulties. This spirit continues in contemporary miko priestesses, living on in the sacred spaces of Japan’s shrines.

For English-speaking readers, the miko priestess may appear exotic and mysterious. Yet understanding their essence reveals a Japanese expression of humanity’s universal longing for the sacred and need for intermediaries with the divine. Through the story of one Japanese goddess, we gain deeper appreciation for both Japanese culture’s profundity and the richness of human spirituality.

The legacy of Ame-no-Uzume reminds us that the sacred can manifest through laughter, that divine power can be channeled through dance, and that women have served as bridges between worlds throughout human history. In every miko priestess performing kagura today, in every shrine ceremony connecting people to their spiritual heritage, the spirit of that first divine dancer lives on, ensuring that the tradition of sacred women dancing with gods continues into the future.

References:

- Ame-no-Uzume-no-Mikoto – Wikipedia Japanese Version Link

- Ame-no-Uzume – Wikipedia (English) Link

- Deities Enshrined at Shrines “Chapter 7: Ame-no-Uzume (Goddess of Entertainment)” – Homemate Link

Editorial Notes:

- The photographic images accompanying this article were created using Midjourney, depicting scenes as envisioned by Zenchantique’s editorial team to illustrate the historical and cultural contexts discussed.

- In translating historical documents and archaic Japanese terminology, we have utilized AI-assisted translation tools for reference. Given the complexity of classical Japanese language and historical texts, we welcome any corrections or clarifications from our readers. Please feel free to contact us if you identify any inaccuracies or have additional insights to share.