Having explored the various interpretations and cultural significance of Yamata no Orochi in previous chapters, we now turn to the complete mythological narrative itself. This epic tale from Japanese mythology, primarily recorded in the Kojiki (712 CE) and Nihon Shoki (720 CE), stands as one of Japan’s most dramatic hero myths—comparable to Perseus and Medusa in Greek mythology or Beowulf’s battle with the dragon in Anglo-Saxon literature.

The story of Yamata no Orochi is fundamentally a tale of redemption. It follows Susanoo-no-Mikoto, the tempestuous storm god, from his disgraceful exile from heaven through his heroic confrontation with the monstrous serpent. This narrative arc—from divine transgressor to monster-slayer—has resonated through Japanese culture for over a millennium.

What follows is the full legendary account of how a banished deity found his purpose, how a terrorized family found salvation, and how one of Japan’s most sacred treasures came into being. This is the story that has inspired countless retellings in art, literature, and popular culture—the timeless battle between Yamata no Orochi and the storm god Susanoo.

The Complete Tale of Yamata no Orochi

Susanoo’s Exile: The Storm God’s Fall from Heaven

In Takamagahara, the celestial realm of Japanese mythology, lived Amaterasu, the sun goddess, and her younger brother Susanoo, the storm god. While Amaterasu embodied grace and order, Susanoo was chaos incarnate: powerful, impulsive, possessed of an untamed spirit that even other deities found impossible to contain.

His transgressions arose not from malice but from an uncontrollable nature combined with divine strength. Like the natural force he embodied, Susanoo would devastate heavenly rice fields, destroy irrigation channels, and play pranks that left the celestial realm in disarray.

The final transgression came when Susanoo hurled a flayed horse—still dripping blood—into the sacred weaving hall where Amaterasu’s attendants worked at divine looms. The maidens fled in terror, and in the chaos, two were fatally injured. This sacrilege against sacred space exceeded all forgiveness.

Even Amaterasu’s infinite patience had limits. She summoned her brother before her, and for the first time, the sun goddess’s voice carried the cold edge of divine judgment: “Susanoo, you have proven yourself unworthy of this realm. You are hereby banished from Takamagahara. Go wherever you will, but never again darken heaven’s gates.”

For the first time in his existence, the storm god felt shame. But the judgment was final, and no amount of regret could undo his actions. With heavy steps, Susanoo descended from heaven to the mortal world below.

The Meeting at Hi River: A Family’s Desperation

The exiled deity wandered until reaching the headwaters of the Hi River in Izumo Province. The valley lay shrouded in unnatural silence that made even a god uneasy. As Susanoo rested by the riverbank, contemplating his fall from grace, he noticed something peculiar floating downstream: a pair of chopsticks.

Where there are chopsticks, there must be people, he reasoned.

Following the river upstream, he discovered cultivated rice fields and eventually a modest dwelling. But as he approached, the sound of bitter weeping reached his ears. Through the doorway, he glimpsed an elderly couple embracing a young woman of extraordinary beauty, all three consumed by grief.

“Why do you weep so?” Susanoo called out.

The old man looked up, startled by this imposing stranger whose bearing marked him as no ordinary traveler. After hesitation, he spoke: “My lord, I am Ashinazuchi, and this is my wife Tenazuchi. We are earthly deities, children of the mountain god Oyamatsumi. This is our daughter, Kushinada-hime.” His voice broke. “We once had eight daughters, each beautiful as spring cherry blossoms. But now… only one remains.”

“What happened to the others?” Susanoo asked, though the old man’s manner suggested a tale of horror.

“Every year,” Ashinazuchi continued, “a monstrous serpent descends from the mountains of Koshi. This creature—Yamata no Orochi, the Eight-Forked Serpent—has devoured seven of our daughters, one each year. Tonight…” He couldn’t continue.

“Tonight it comes for the last,” Tenazuchi finished, her voice hollow with despair.

The Divine Strategy: Sake, Swords, and Serpent-Slaying

Susanoo studied the family before him. Here was a chance—perhaps his only chance—for redemption. “Describe this serpent to me.”

“It is no ordinary dragon, my lord,” Ashinazuchi whispered. “It has eight heads and eight tails. Its body stretches across eight valleys and eight hills. Moss and cedars grow upon its back, and its eyes burn like winter cherries. The earth trembles at its approach, and its breath poisons the very air.”

The storm god smiled—a fierce expression that held no mirth. “I will slay your serpent,” he declared. “But I have one condition.”

The elderly couple prostrated themselves. “Anything, lord! Name your price!”

“When the beast is dead, I want Kushinada-hime as my bride.”

The parents exchanged glances. The young woman herself looked up at this strange, powerful figure who had appeared at their darkest hour.

“First, honored sir,” Ashinazuchi ventured carefully, “might we know who offers us this bargain?”

“I am Susanoo, brother of Amaterasu, exiled from heaven but still a god.”

The revelation stunned them. To have a deity—even an exiled one—take interest in their plight exceeded their wildest hopes. They readily agreed to his terms.

Susanoo immediately set his plan in motion. First, he transformed Kushinada-hime into an ornate comb, which he placed in his hair for safekeeping. Then he instructed the old couple: “Brew the strongest sake you can make—eight vats full. Build a fence around your dwelling with eight gates, and at each gate, construct a platform. Place one vat of sake on each platform.”

As darkness fell, an unnatural red glow emanated from the mountains of Koshi, as if the peaks themselves were ablaze. The wind carried the stench of decay and blood. Soon, sixteen crimson lights appeared in the distance—the eyes of the approaching monster.

Yamata no Orochi was everything the old man had described and more. Its eight heads swayed independently, each seeking prey. The earth groaned under its weight as it approached the dwelling, drawn by the scent of its final victim.

But the serpent paused. The aroma of sake—the sacred wine of the gods—filled the air. Unable to resist, each head plunged into a different vat, drinking deeply. The sake was no ordinary brew but yashiori no sake, eight times distilled and potent enough to affect even monsters.

Soon, the great serpent’s movements grew sluggish. Its heads drooped one by one until the monster collapsed in a drunken stupor, its thunderous snores shaking the valley.

Susanoo emerged from hiding, drawing his ten-span sword—Totsuka no Tsurugi, the sword of divine punishment. With practiced precision, he began severing the monster’s heads and tails, working methodically through the beast’s body. The Hi River ran crimson with the serpent’s blood.

The Discovery of the Sacred Sword: The Birth of Kusanagi and the Gift to Amaterasu

As his blade cleaved through the fourth tail, it struck something harder than bone or scale. Investigating, Susanoo discovered within the tail’s flesh a sword of incredible beauty and power. Purple mist rose from the blade, and Susanoo recognized it immediately as a divine weapon.

“This is why the mountains of Koshi were perpetually shrouded in clouds,” he murmured. “This blade commanded the very mists.” He named it Ame-no-Murakumo-no-Tsurugi—the Sword of the Gathering Clouds of Heaven.

With the monster slain, Susanoo removed the ornate comb from his hair and breathed upon it gently. In an instant, Kushinada-hime stood before him once more, whole and unharmed.

“The danger has passed,” he told her, his voice gentler than she had yet heard it. “You are safe now.” He showed her the divine sword. “This came from within the serpent’s tail—a blade of heaven itself. I shall present it to my sister Amaterasu as a peace offering. Perhaps it will help mend what my foolishness has broken.”

He took her hand in his. “After I deliver this gift, we shall find a place to call our own—somewhere the sun shines warmly and the land is fertile. We’ll build a life there together, far from the sorrows of the past.”

At that moment, Ashinazuchi and Tenazuchi emerged from their hiding place, scarcely believing their eyes. The valley, which had reeked of death moments before, now seemed peaceful under the starlight. Their last daughter lived, and the monster that had terrorized them for seven years lay in pieces.

“The serpent is no more,” Susanoo announced. “As promised, I claim Kushinada-hime as my bride. Live long and in peace, knowing your bloodline continues and your tormentor is vanquished.”

The elderly couple could only bow repeatedly, overwhelmed by joy and gratitude. They had offered their daughter to save her life, but gained a god as a son-in-law—even an exiled god exceeded their wildest hopes.

Taking the divine sword in his right hand and Kushinada-hime’s hand in his left, Susanoo began the journey back to the heavenly realm. Though he had been banished in disgrace, he now returned with proof of his redemption: a divine treasure for his sister and a deed of heroism that would echo through the ages.

Thus ends the tale of how the storm god found his purpose in exile, how a monster’s terror was ended, and how a sacred sword came to rest among the imperial treasures of Japan—for the Ame-no-Murakumo-no-Tsurugi would later be known as Kusanagi, the grass-cutting sword, one of the three sacred treasures of the Japanese emperors.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of the Yamata no Orochi Tale

The complete tale of Yamata no Orochi represents far more than an entertaining story from Japanese mythology—it embodies fundamental themes that continue to resonate across cultures and centuries. Through Susanoo’s journey from disgrace to redemption, we witness a universal narrative arc: the flawed hero who finds purpose through protecting the innocent.

The slaying of Yamata no Orochi marks a pivotal moment in Japanese mythology, not merely for its dramatic action but for what it represents. Susanoo’s transformation from a destructive force in heaven to a protective deity on earth mirrors humanity’s own struggle to channel chaotic impulses toward constructive ends. His use of cunning over brute force—employing sake to outwit the serpent—demonstrates that wisdom often triumphs where strength alone would fail.

Moreover, the discovery of Kusanagi within Yamata no Orochi‘s tail adds layers of meaning to the narrative. This divine sword, later becoming one of Japan’s three imperial treasures, suggests that even from destruction and evil can emerge tools of legitimate authority and protection. The sword’s presentation to Amaterasu symbolizes not just Susanoo’s personal redemption but the restoration of cosmic order.

The marriage of Susanoo and Kushinada-hime provides the tale’s emotional resolution. What began as a story of exile and monster-slaying concludes with the establishment of a new divine lineage in Izumo, transforming a narrative of destruction into one of creation and continuity.

This timeless story from Japanese mythology continues to captivate because it speaks to eternal human experiences: redemption after failure, courage in the face of overwhelming odds, and the triumph of civilization over chaos. Whether encountered in ancient texts or modern adaptations, the tale of Susanoo and Yamata no Orochi remains one of world mythology’s great dragon-slaying epics—a testament to the enduring power of mythological storytelling.

References

- Wikipedia Japan “Yamata no Orochi”

- Kusano Takumi & Tobe Tamio, Nihon Yōkai Hakubutsukan [Japanese Monster Museum], 1994, pp.12-14

- Saito Koichi, Nihon Mukashibanashi: Eiyū no Maki [Japanese Folk Tales: Heroes Volume], Reimeisha, 1946, pp.3-29

To learn more about the various historical interpretations and cultural significance of Yamata no Orochi, please refer to our comprehensive analysis article.

Editorial Notes

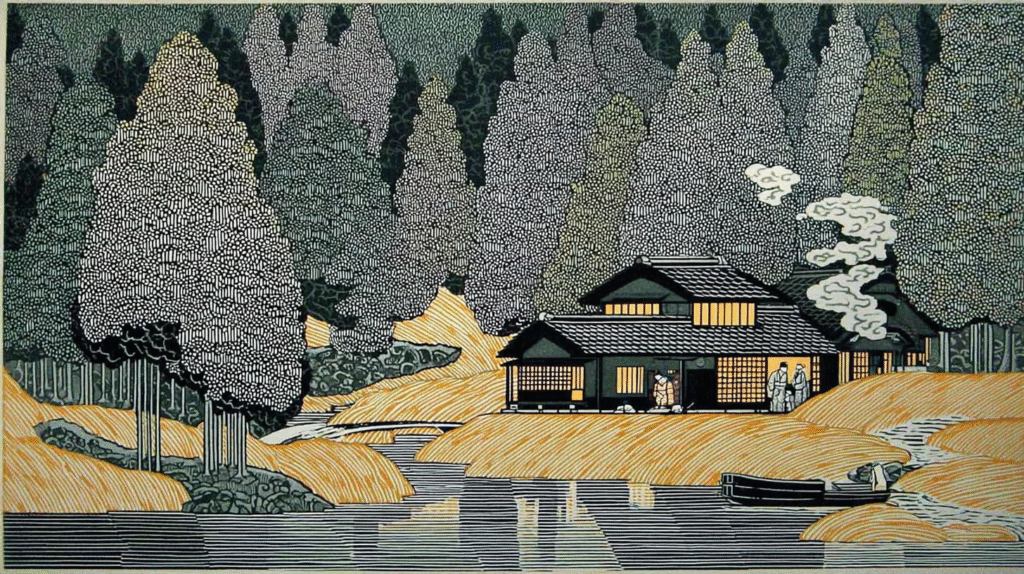

- The visual images accompanying this article were created using Midjourney, depicting scenes as envisioned by Zenchantique’s editorial team.

- AI-assisted translation was utilized for certain archaic Japanese terms and classical texts. Should you notice any inaccuracies or wish to provide corrections, please don’t hesitate to contact us.