Among all the creatures in Japanese mythology, none commands as overwhelming a presence as Yamata no Orochi (八岐大蛇, literally “eight-branched giant serpent”). Recorded as Yamata no Orochi in the Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan, completed in 720 CE) and as Yamata no Orochi (八俣遠呂智) in the Kojiki (Records of Ancient Matters, completed in 712 CE)—Japan’s oldest surviving historical texts—this legendary creature with eight heads and eight tails transcends mere monster tales to become deeply embedded in the Japanese spiritual consciousness.

The scale of Yamata no Orochi in Japanese mythology defies comprehension. Its body stretched across eight valleys and eight peaks, with moss growing on its back where Japanese cedar (cryptomeria) and camphor trees flourished—a description that transforms the creature into a living mountain range. Its eyes glowed crimson like winter cherry lanterns (physalis alkekengi, known as hōzuki in Japanese), its belly oozed with blood, and from its mouth erupted poisonous flames—a vivid manifestation of primordial terror that haunted ancient Japanese imagination.

The Anatomy of Yamata no Orochi – Decoding the Monster

The Astounding Physique: Eight Heads, Eight Tails, and a Mountain-Spanning Body

To comprehend Yamata no Orochi’s significance in Japanese mythology, we must first decode its name. “Yamata” (八岐) translates to “eight-forked” or “split into eight,” directly referencing the creature’s eight heads and eight tails. Yet this multiplicity barely hints at the monster’s true scale. Ancient texts describe its length as covering eight valleys and eight hills—in modern terms, suggesting a creature stretching dozens of kilometers.

The description of its moss-covered back, where cedar and camphor trees grew, elevates Yamata no Orochi beyond a mere biological entity in Japanese mythology. This detail transforms the serpent into nature incarnate—not just a creature living in the natural world, but the embodiment of mountains and forests themselves. The blood-slick belly adds another layer of otherworldly horror, emphasizing the creature’s position between the natural and supernatural realms.

Etymology: Decoding the Ancient Name

The renowned 18th-century scholar Motoori Norinaga, in his seminal work Kojiki-den (Commentary on the Kojiki), argued that the creature’s name should be read as “Yamata Orochi” without the possessive particle “no.” According to historical Japanese linguistics, “ya” (ヤ) signified peaks or summits, while “chi” (チ) denoted entities possessing violent, destructive power. Thus, the very name Yamata no Orochi encapsulates both its mountain-like enormity and terrifying strength—a linguistic encoding of fear that has persisted through Japanese mythology for over a millennium.

Regional Connections: The Serpent from Koshi Province

The Kojiki provides crucial geographical context: “The eight-forked serpent of Koshi comes every year” (高志之八俣遠呂智、年毎に来たり). This positions Yamata no Orochi as originating from Koshi Province—the ancient designation for the Hokuriku region along the Sea of Japan, encompassing modern-day Niigata, Toyama, Ishikawa, and Fukui prefectures. This geographical specificity transcends mere mythological detail, suggesting deeper historical and cultural connections that scholars continue to debate.

Multiple Interpretations Behind the Legend

The Flood Incarnation Theory: Natural Disasters Personified

The most widely accepted academic interpretation views Yamata no Orochi as the personification of catastrophic flooding—a reading that illuminates the practical concerns underlying Japanese mythology. The eight heads represent the chaotic tributaries of a flooding river system, while the serpentine body symbolizes the meandering, destructive path of raging waters. In this framework, Orochi embodies the water deity’s wrathful aspect, while Kushinada-hime (literally “rice paddy princess”) represents the vulnerable agricultural lands.

This interpretation transforms the myth into a narrative about Japan’s eternal struggle with water—both life-giving and life-destroying. For an agricultural society dependent on controlled irrigation, flooding represented the ultimate existential threat, making Yamata no Orochi a perfect antagonist in Japanese mythology’s foundational stories.

The Metallurgy Connection: Iron, Blood, and Ancient Technology

A compelling alternative theory links Yamata no Orochi to ancient iron production, revealing how Japanese mythology often encoded technological and economic realities. The Izumo region (modern Shimane Prefecture) was historically renowned for iron production using a technique called tatara—and specifically “nodatara,” an open-air smelting method.

In this interpretation, the serpent represents molten iron flowing from smelting furnaces, with its blood-red coloration matching the iron-oxide-rich water that would have stained rivers near production sites. The creature’s defeat by Susanoo thus symbolizes the conquest and control of iron-producing communities—a precious resource that would have represented both wealth and military power in ancient Japan.

Archaeological evidence supports this connection. Numerous undated nodatara sites dot the mountainous regions near Izumo, their locations corresponding with areas mentioned in Yamata no Orochi myths. The discovery of the sacred sword Kusanagi (grass-cutting sword) within the serpent’s tail gains new meaning in this context—the mythological transformation of metallurgical mastery into divine weaponry.

Political Symbolism: The Yamato Conquest Narrative

Japanese mythology often serves as a coded history of political conquest, and Yamata no Orochi fits this pattern perfectly. When the Yamato court (the precursor to the Japanese imperial line) expanded into the Izumo region, they encountered indigenous peoples with their own religious and political systems. These communities likely worshipped nature deities, with the serpent serving as a primary divine symbol.

By casting Yamata no Orochi as a malevolent monster requiring divine intervention, the conquering Yamato forces could justify their dominance while demonizing local religious practices. This political reading of Japanese mythology reveals how sacred narratives legitimized temporal power—a pattern repeated throughout world history.

The Jade Trade Theory: Economic Competition in Ancient Japan

The philosopher Umehara Takeshi proposed a fascinating economic interpretation, noting that Koshi Province contained Japan’s only jade sources (specifically the Hime River valley in modern Niigata Prefecture’s Itoigawa City). In ancient East Asia, jade represented ultimate prestige—more valuable than gold or silver for ritual and political purposes.

Umehara theorized that “the eight-forked serpent of Koshi” symbolized wealthy, powerful invaders from this jade-rich region who dominated the Izumo area through economic superiority. Yamata no Orochi’s annual arrival to claim maidens might represent tribute payments or forced marriages cementing political alliances. This interpretation adds economic warfare to Japanese mythology’s already complex layers of meaning.

The physicist Torahiko Terada offered yet another perspective, suggesting that Yamata no Orochi evoked images of lava flows. This scientific interpretation views the monster as a mythological representation of volcanic terror, with flowing lava transformed into a giant serpent in the collective imagination.

The Historical Evolution of Snake Worship in Japan

From Sacred to Sinister: Buddhism’s Influence on Snake Imagery

Snakes held sacred status as among Japan’s oldest deities. During the Jomon period (14,000-300 BCE), they were revered as mountain gods. With the advent of rice cultivation in the Yayoi period (300 BCE-300 CE), snakes evolved into water deities managing irrigation systems. The Nihon Shoki describes how Ōmononushi, the deity of Mount Miwa, appeared in snake form, demonstrating the serpent’s divine status in early Japanese mythology.

However, Buddhism’s arrival in the 6th century CE dramatically transformed snake imagery. As Buddhism unified Japan’s spiritual culture, localized indigenous beliefs retreated to the margins. Snake deities were banished to mountains and riverbanks, gradually losing their divine power and transforming into malevolent monsters.

Mountain Gods and Water Deities: The Snake’s Original Spiritual Power

Originally, snakes embodied the spirits of mountains and rivers. Their spiritual power brought fertility, ensuring abundant harvests as agricultural deities. Yamata no Orochi in Japanese mythology likely began as such a benevolent force rather than an evil entity.

The description of Yamata no Orochi—its body covering mountains and valleys, moss and trees growing on its back—depicts the natural mountain landscape itself. This imagery reveals the serpent as an earth spirit, a mountain deity. While agricultural communities revered water as divine blessing, they simultaneously feared flood damage, gradually emphasizing only the snake deity’s destructive aspects.

Archaeological Evidence: Snake Stones and Shrine Relics

Yamada Shrine in Tsunemi, Saku City, Nagano Prefecture, houses the “hebi-ishi” (snake stone), believed connected to Yamata no Orochi. According to local tradition, when the serpent was slain by Susanoo, its soul remained in stone form. Legends tell of frogs placed on the stone mysteriously vanishing, and the stone itself growing yearly until locals enshrined it as a protective deity, whereupon its growth ceased.

Susa Shrine in Izumo houses what are claimed to be Yamata no Orochi‘s bones, demonstrating that serpent worship extended beyond mere mythology into actual folk religious practice.

Yamata no Orochi in Contemporary Culture

Sacred Relics: The Bones Preserved at Susa Shrine

Susa Shrine in Susa-cho, Izumo City, Shimane Prefecture, dedicated to Susanoo-no-Mikoto, carefully preserves objects claimed to be Yamata no Orochi‘s bones. While scientific analysis hasn’t determined their actual origin, local communities continue venerating them as sacred relics.

The Growing Snake Stone: Yamada Shrine’s Mystical Legend

The snake stone at Yamada Shrine carries additional fascinating lore. This stone allegedly increased in size annually, breaking through shelters built to contain it. Only when locals enshrined it as a tutelary deity did its growth cease. Such legends of seemingly living stones suggest that Yamata no Orochi‘s spiritual power continues in popular belief.

Pop Culture Presence: The Serpent in Modern Media

Yamata no Orochi frequently appears in contemporary popular culture. In anime, films, and video games, the creature undergoes constant reinterpretation and revival. These works portray Yamata no Orochi variously as villain or guardian deity, spreading awareness of Japanese mythology globally.

Conclusion: What Yamata no Orochi Tells Us in the 21st Century

The tale of Yamata no Orochi is far more than an ancient monster story. It serves as a mirror reflecting Japanese perspectives on nature, religion, and the development of civilization. Floods, metallurgy, political conquest, control of trade routes—all these interpretations reveal the multilayered meanings within this myth from Japanese mythology.

Today in the 21st century, we have overcome many natural threats through science and technology. Yet the story of Yamata no Orochi continues speaking to us through its universal themes: awe before nature’s power and human courage to overcome it. The transformation of a once-feared natural spirit into a beloved cultural icon symbolizes the evolving relationship between humanity and nature.

The enduring power of Yamata no Orochi in Japanese mythology lies not just in its role as a fearsome monster, but in what it represents about the human condition—our fears, our triumphs, and our endless fascination with forces greater than ourselves.

References

- Wikipedia Japan “Yamata no Orochi”

- Kusano Takumi & Tobe Tamio, Nihon Yōkai Hakubutsukan [Japanese Monster Museum], 1994, pp.12-14

- Saito Koichi, Nihon Mukashibanashi: Eiyū no Maki [Japanese Folk Tales: Heroes Volume], Reimeisha, 1946, pp.3-29

To learn more about the various historical interpretations and cultural significance of Yamata no Orochi, please refer to our comprehensive analysis article.

Editorial Notes

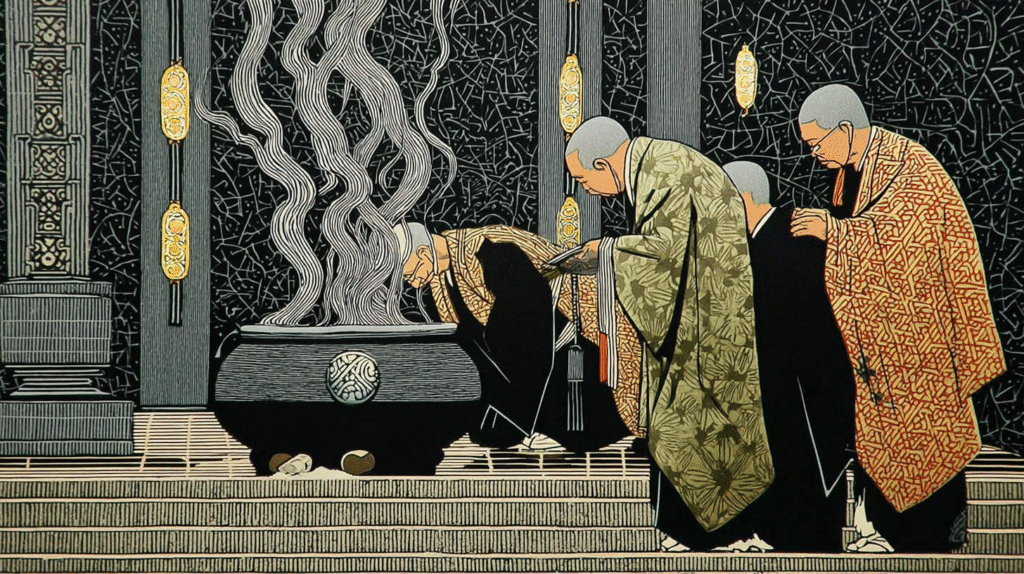

- The visual images accompanying this article were created using Midjourney, depicting scenes as envisioned by Zenchantique’s editorial team.

- AI-assisted translation was utilized for certain archaic Japanese terms and classical texts. Should you notice any inaccuracies or wish to provide corrections, please don’t hesitate to contact us.