The global success of anime series like “Jujutsu Kaisen” has recently thrust Japanese mysticism into the international spotlight. Behind these entertainment portrayals of flashy magical battles lies a rich cultural tradition with over a thousand years of history. The roots of Japanese mysticism run deep in traditional religious practices including Onmyōdō (the Way of Yin and Yang), esoteric Buddhism (Mikkyō), and mountain asceticism (Shugendō).

This article explores the essence of Japanese mysticism, its historical development, and its continued significance in contemporary society.

Understanding Japanese Mysticism: Fundamental Concepts

Japanese mysticism encompasses magical-religious practices that employ words (spells), tools (magical objects), and ritual actions to achieve desired outcomes through supernatural assistance. In Japanese, the term “majinai” is also used, referring to more casual, everyday magical practices with diminished expectations of efficacy.

Even in modern life, aspects of Japanese mysticism persist in subtle ways. Many Japanese people still consider auspicious dates for weddings (selecting “taian” days on the traditional calendar) or avoid certain dates (“tomobiki”) for funerals—practices rooted in ancient divinatory traditions.

While religion generally assumes a subordinate relationship to deities, Japanese mysticism often involves practitioners actively manipulating supernatural forces. However, these domains frequently overlap—temple and shrine prayers often carry both religious devotion and expectations of magical efficacy.

Though scientific advancement has undoubtedly narrowed the domain of Japanese mysticism, it continues to complement science in areas beyond empirical explanation, fulfilling psychological and cultural functions.

The Historical Development of Japanese Mysticism

Japanese mysticism dates back to the Jōmon period (14,000-300 BCE), with archaeological evidence suggesting magical elements in burial practices. By the 3rd century CE, the shaman-queen Himiko reportedly ruled the Yamatai kingdom through her mastery of magical arts, as recorded in Chinese chronicles.

The 6th century brought significant changes with the influx of Chinese culture. Yin-yang philosophy, Taoist magical concepts, and Buddhist esoteric practices were incorporated into indigenous Japanese magical traditions. During the Heian period (794-1185), Onmyōdō flourished, with the imperial court establishing the Onmyōryō (Bureau of Yin and Yang) to handle state rituals and magical countermeasures against disasters.

Medieval Japan saw the development of esoteric Buddhism and Shugendō, with fire rituals (goma) and other magical ceremonies addressing people’s practical concerns. During the Edo period (1603-1868), texts on ninjutsu like “Mansen Shukai” described “escape techniques” (tonpō) such as “water escape” (suiton) and “fire escape” (katon)—techniques that have inspired modern anime portrayals. These ninja arts reflected influences from Onmyōdō’s five-element theory and esoteric Buddhist ritual practices.

Principles and Techniques of Japanese Mysticism

British anthropologist James Frazer identified two fundamental principles of magic worldwide that are clearly evident in Japanese mysticism: “sympathetic magic” (imitation) and “contagious magic” (contact).

Sympathetic magic operates on the principle that “like produces like.” Examples include rainmaking rituals that mimic thunder and downpours, or harming straw effigies to affect the resembled target. Contagious magic follows the principle that “things once in contact continue to influence each other.” This includes using a target’s hair, nails, or clothing in harmful rituals.

Archaeological excavations at the Heijō Palace site in Nara have uncovered wooden figurines (hitogata) with nails and attached hair, demonstrating that such magical practices have continued from ancient times to the present.

A distinctive feature of Japanese mysticism is the concept of kotodama—the belief that spiritual power resides in words. This belief is deeply embedded in Japanese culture, making incantations central to magical practice. From esoteric Buddhist mantras to folk magical formulas, these are not mere word sequences but combinations of sounds and rhythms believed to activate spiritual power.

Japanese Mystical Practitioners

Onmyōji and Abe no Seimei

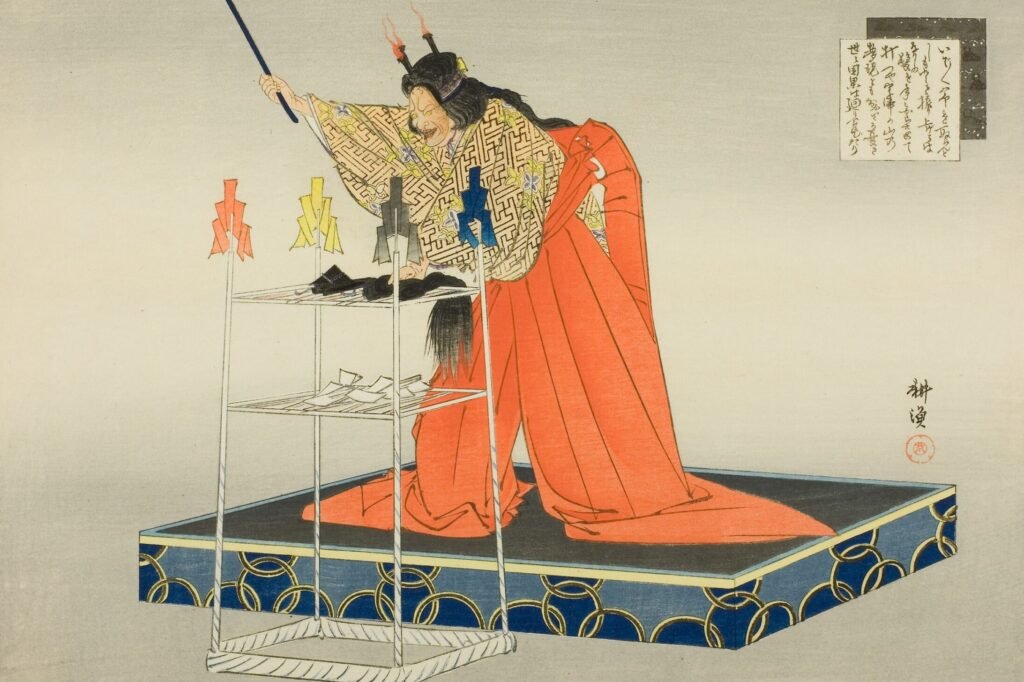

Among the most famous practitioners of Japanese mysticism is Abe no Seimei, an Onmyōji from the Heian period. While historical records suggest Seimei was primarily an astronomer and diviner, later folklore portrays him as a powerful magician who could control spirit servants (shikigami), exorcise malevolent spirits, and perceive hidden truths.

These legendary accounts of Seimei continue to inspire contemporary novels, manga, anime, and drama, perpetuating the fascination with Japanese mysticism.

Esoteric Buddhist Practitioners and Mountain Ascetics

Esoteric Buddhist ritual specialists called “genja” were renowned for their magical techniques. Kūkai (Kōbō Daishi), the founder of Shingon Buddhism, was later celebrated in legend as a powerful magician who supposedly demonstrated supernatural abilities during his studies in China.

Shugendō founder En no Gyōja appears in the “Nihon Ryōiki” chronicles as a magician who commanded demons to build bridges between mountains and could escape from imprisonment using his magical powers.

Female Practitioners and Mediums

Women played crucial roles in Japanese mysticism, particularly as miko (shrine maidens) with shamanistic abilities. In ancient Japan, female shamans communicated divine will, with Himiko representing perhaps the most famous example.

During the Heian period and beyond, miko served at shrines performing ritual archery and entering trance states to deliver oracles. From medieval to early modern times, itinerant female religious practitioners called “ichiko” or “miko” conducted spirit possession, divination, and curse removal rituals.

The Dual Nature of Japanese Mysticism

Japanese mysticism itself carries no inherent moral value—its ethical character depends entirely on its purpose and application. Rainmaking rituals might seem beneficial, but legends suggest some may have involved human sacrifice to water deities, making them anything but “beneficial” to the victims and their families.

This ambiguity places Japanese mysticism perpetually on the boundary between beneficial and harmful practice, with context and perspective determining its ethical evaluation.

Japanese Mysticism in Contemporary Society

Japanese mysticism persists in three main forms in modern society:

First, as institutionalized religious practices in temples and shrines, where prayer services and protective amulets remain popular. Second, as unconscious customs and habits like traditional seasonal rituals with magical origins. Third, as reinterpreted practices in new contexts like occult and spiritual movements.

Particularly noteworthy is the portrayal of Japanese mysticism in popular culture. Anime series like “Jujutsu Kaisen,” “NARUTO,” and “Demon Slayer” incorporate elements of traditional Japanese mysticism while reconstructing them in creative fictional worlds. These portrayals, while not historically accurate, effectively convey the atmosphere and worldview of traditional Japanese mysticism to contemporary audiences.

In the art world, the connection between art and mysticism was famously noted by artist Tarō Okamoto. Both art and Japanese mysticism draw on deep psychological and primal energies, and many contemporary Japanese artists incorporate mystical elements in their work.

The Significance of Japanese Mysticism Today

One reason Japanese Mystical Traditions maintains relevance is its psychological function in providing comfort amid uncertainty. Students seeking protective charms for exams or patients visiting temples after medical treatments find solace in “doing something” to address their anxiety, regardless of scientific efficacy.

In an era of globalization, Japanese mysticism also serves as a cultural identifier. Traditional practices with mystical elements like Setsubun bean-throwing, Tanabata, and Obon rituals symbolize Japanese cultural uniqueness and are increasingly valued as cultural heritage.

Conclusion: Japanese Mysticism Bridging Past and Future

Japanese mysticism is not merely a historical relic but a living cultural asset that continues to evolve. Behind these practices lie universal values of coexistence with nature, reverence for life, and community bonds.

With anime and manga introducing aspects of Japanese mysticism to younger generations and international audiences, now is an opportune moment to reconsider its essential meaning and value.

Science and mysticism might seem contradictory, but both spring from the same wellspring of human creativity and inquiry. Understanding the history and diversity of Japanese mysticism offers insight into our cultural roots while providing inspiration for future cultural creation.

This article presents academic insights into Japanese mysticism based on cultural and historical research. It does not endorse any specific religious position or guarantee magical efficacy. Some practices described may be problematic under contemporary legal and ethical standards and should be approached with appropriate consideration.

Explore more articles about Japanese Culture! Thank you! 🙂