Japanese scroll paintings, known as emakimono or simply emaki, represent a unique art form that flourished from the Heian period (794-1185) through the Muromachi period (1336-1573). These narrative handscrolls combine text passages (kotobagaki) with paintings to create a distinctive artistic expression. Among the various genres of Japanese scroll paintings, temple and shrine origin stories (jisha engi) played a crucial role in spreading religious faith and establishing institutional legitimacy. The Inaba-do Yakushi Engi Emaki, housed at Byodo-ji Temple (commonly known as Inaba-do) in Kyoto, stands as an exemplary work of medieval Japanese scroll paintings, commanding attention from both art historical and literary perspectives.

The Miraculous Tale Told Through Japanese Scroll Paintings

Encounter with Yakushi Nyorai

The narrative begins in the third year of Chotoku (997) during Emperor Ichijo’s reign, in the full bloom of spring. The protagonist, Tachibana no Yukihira, sets out on an imperial mission to visit the primary shrine (ichinomiya) of Inaba Province (present-day eastern Tottori Prefecture). However, on his return journey, Yukihira falls gravely ill. In a prophetic dream, he learns of a sacred log that has appeared at Karutsu Beach for the salvation of all sentient beings.

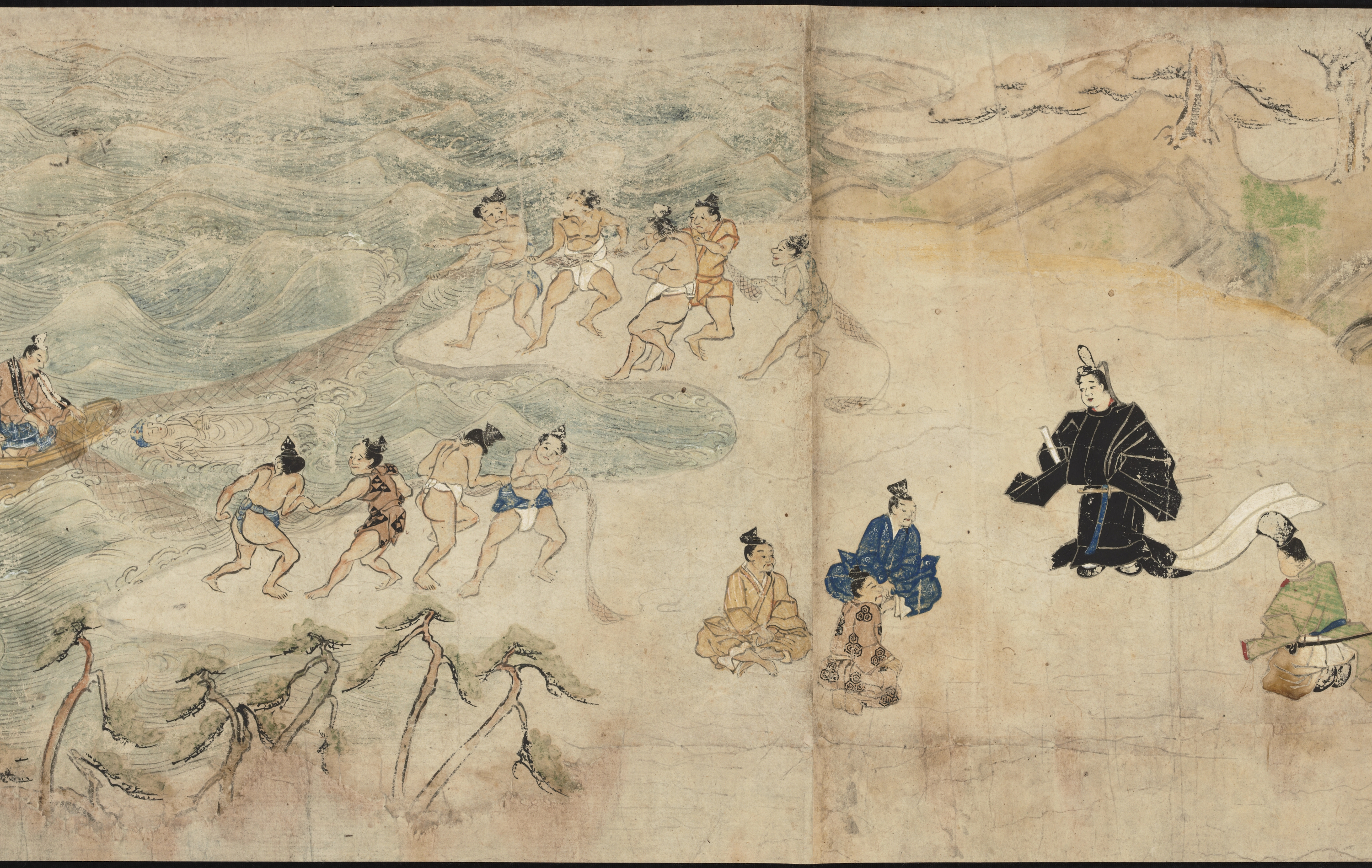

One of the most impressive scenes in these Japanese scroll paintings depicts the moment when the Yakushi Nyorai (Medicine Buddha) statue is pulled from the sea. When the luminous driftwood is hauled up with nets, it reveals itself to be a life-sized statue of Yakushi Nyorai—a miracle captured by the artist’s brush. This scene follows traditional Buddhist narrative painting conventions while displaying unique innovations in wave representation and figure placement that distinguish these Japanese scroll paintings from their contemporaries.

The Flying Buddha Statue

In the fourth month of Choho 5 (1003), an even more miraculous event occurs. The Yakushi Nyorai statue, which had been enshrined in Inaba Province, flies through the air to knock on the gate of Yukihira’s residence in Kyoto. This supernatural occurrence, rendered through the unique visual language of Japanese scroll paintings, creates a powerful impression on viewers. The depiction of Yakushi Nyorai flying in the form of a monk follows expressive conventions found in other origin story scrolls like the Zenko-ji Engi, yet incorporates distinctive interpretations specific to the Inaba-do tradition.

Artistic Features and Current Condition of the Scroll

Extant Works

The Important Cultural Property designated scroll held by the Tokyo National Museum (color on paper, 33.6 × 785.0 cm) is attributed to the 14th century Kamakura period. However, the scroll suffered damage in the Great Tenmei Fire, losing portions of the beginning and end, with some text passages now missing. In addition to this work, the following copies of these Japanese scroll paintings are known:

- One volume of excerpted copies from a three-volume set attributed to painter Tosa Hogen and calligraphers Shimizudani and Saionji

- One volume copy of the final scroll with unknown artist and text attributed to Emperor Go-Daigo

- One final volume from the former Kawada family collection of Mikawa Koromo domain

Characteristics of the Painting Style

The painted portions of these Japanese scroll paintings inherit the yamato-e (traditional Japanese painting) tradition of the Kamakura period while maintaining a somewhat elegant and archaic atmosphere. However, when compared to masterpieces like the Shigisan Engi or Kegon Engi, the compositions lack tension and convey an overall impression of weakness. This suggests that the visual expression fails to fully respond to the literary imagination evoked by the text passages—a common challenge in Japanese scroll paintings where narrative and image must work in harmony.

Literary Value and Evangelical Literature

Evaluation by Origuchi Shinobu

The folklorist and Japanese literature scholar Origuchi Shinobu evaluated the Inaba-do Engi as “a woman’s narrative sermon (sekkyō) describing the merits of Yakushi Nyorai, an ancient form of jōruri puppet theater narrative.” This recognition identifies the prototype for stories later transmitted as “Inaba-do Kaichō” and “Inaba Yakushi Denki” within these Japanese scroll paintings.

As an Early Form of Honji-mono

The composition combining Yakushi Nyorai’s original ground (honji), his miraculous powers, and the temple’s founding into a single narrative marks these Japanese scroll paintings as noteworthy early examples of the honji-mono (original ground stories) genre that became common in the Muromachi period. Occupying the same literary historical position as the evangelical literature shown in the Shintōshū collection, this work represents an important piece for understanding the development of medievalJapanese religious literature.

Historical Transformation of Inaba-do and Development of Faith

From a Small “Miracle Hall” to a Temple in the Heian Period

In the late Heian period, Inaba-do existed merely as a small “miracle hall” (shō reigenjo). The Chūyūki diary (entry from the 21st day of the first month of Jōtoku 1) records: “To the east of Karasuma there is a small miracle hall, popularly called Inaba-do,” indicating it was a modest hall known for healing miracles through the power of Yakushi Nyorai.

Particularly interesting is the Chūyūki entry (fourth day of the seventh month of Ten’ei 3) stating: “Medicine called bukuryō has arrived from Inaba Province.” This reveals that Inaba Province was known as a source of medicinal herbs, suggesting the background for the connection between Yakushi worship and the place name Inaba. In ancient times, Yakushi faith was not merely Buddha statue veneration but was intimately connected with actual medical treatment and pharmaceutical practices—a unique aspect reflected in these Japanese scroll paintings.

Sectarian Changes and the Influence of the Ji School

From the Kamakura period onward, Inaba-do experienced complex sectarian transitions. Initially, as a subsidiary temple of Shōbodai-in (the votive temple of Emperor Shirakawa’s sister, Empress Atsuko, consort of Emperor Horikawa), it maintained close ties with the imperial court. Subsequently, it passed from Shingon Buddhism to the control of Shōgo-in, and eventually came under the influence of the Ji school of Pure Land Buddhism.

The Ippen Hijiri-e (Illustrated Biography of Saint Ippen) records an episode from Kōan 7 (1284) when Ippen stayed at Inaba-do. The description of the temple administrator, Minbu Hokkyō Kakujun, receiving a message from the principal image in a dream illustrates how Inaba-do developed deep connections with the Ji school—connections that would influence how these Japanese scroll paintings were interpreted and transmitted.

Background and Intent of Scroll Production

As a Tale of the Three-Country Transmission Buddha

The Inaba-do Engi, like the Zenkō-ji Engi, was conceived as a story of a “Buddha transmitted through three countries” (sangoku denrai butsu). While the extant Japanese scroll paintings depict only events in Japan, the original narrative was a grand tale tracing the Buddha statue’s provenance through India (Tenjiku), China (Shintan), and Japan.

The Complex Process of the Origin Story’s Formation

The formation process of this origin story was not simple. Beginning as brief oral traditions, various elements were added over time. Particularly noteworthy is the historicity of the protagonist, Tachibana no Yukihira. The Midō Kanpaku-ki diary (entry from the 29th day of the twelfth month of Kankō 2) confirms that Tachibana no Yukihira actually served as Governor of Inaba, though the connection to the miraculous events depicted in these Japanese scroll paintings remains unclear.

The Significance of Inaba-do Engi in Japanese Scroll Painting Culture

Crystallization of Popular Faith and Art

The most distinctive feature of the Inaba-do Engi Emaki is that, unlike many other temple and shrine origin stories associated with aristocratic or warrior family temples, it arose and developed based on popular faith. The process by which simple faith in Yakushi Nyorai was refined into sophisticated narrative and ultimately crystallized in the art form of Japanese scroll paintings vividly demonstrates one aspect of Japanese religious culture.

Fusion of Design and Narrative

The emakimono format can be considered a precursor to modern visual storytelling. The Inaba-do Engi Emaki draws viewers into its narrative world through the mutual complementation of text and painting. In particular, scenes such as the Yakushi Nyorai statue being pulled from the sea or flying toward Kyoto demonstrate the rich imagination of Japanese art in visualizing supernatural events—a hallmark of great Japanese scroll paintings.

The Inaba-do Engi Emaki is not merely a religious painting narrating a temple’s origins. It represents a comprehensive artwork crystallizing the faith, imagination, and artistic sensibility of medieval Japanese people. The process by which simple faith in Yakushi Nyorai developed into sophisticated narrative over time and was ultimately visualized in the scroll format illustrates the multilayered nature and creativity of Japanese culture.

In the contemporary era, the significance of these Japanese scroll paintings is far from being a thing of the past. The fusion of narrative and visual expression, the relationship between religion and art, and the vitality of popular culture—all issues presented by the Inaba-do Engi Emaki continue to offer us numerous insights. As we study and preserve these remarkable Japanese scroll paintings, we gain deeper understanding not only of medieval Japanese culture but also of the universal human impulse to combine word and image in the service of spiritual expression.

References

- Zoku Nihon Emakimono Shūsei (Continued Collection of Japanese Scroll Paintings), Vol. 1, edited by Mizoguchi Teijirō et al., Yūzankaku, 1945

- Museum (2), edited by Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo National Museum, May 1951

- Shinshū Nihon Emakimono Zenshū (New Collection of Japanese Scroll Paintings), Vol. 30, Kadokawa Shoten, June 1980

- Kokugakuin Zasshi 60(1/2), Kokugakuin University, February 1959

A Note on Understanding Japanese Scroll Paintings

For Western audiences encountering Japanese scroll paintings for the first time, it’s important to understand that these works function quite differently from Western narrative art. Unlike Renaissance frescoes or illuminated manuscripts that often present scenes in discrete panels, Japanese scroll paintings unfold continuously as the viewer unrolls the scroll from right to left, creating a temporal dimension to the viewing experience. This format, which emerged in the Heian period and reached its zenith during the Kamakura and Muromachi periods, allows for a unique integration of time, space, and narrative that predates cinema by centuries.

The Inaba-do Engi Emaki exemplifies the sophisticated visual vocabulary that developed within the tradition of Japanese scroll paintings. The alternation between text and image creates rhythm and pacing, while artistic devices such as fukinuki yatai (blown-off roof) technique—where buildings are shown without roofs to reveal interior scenes—and iji-dōzu (different time, same illustration)—where multiple temporal moments appear in a single scene—demonstrate the innovative solutions Japanese artists developed for visual storytelling.

Understanding the cultural context of these Japanese scroll paintings also requires appreciating the role of Buddhism in medieval Japanese society. The Medicine Buddha (Yakushi Nyorai) featured in the Inaba-do Engi was particularly important for common people, as this Buddha was believed to cure illness and ensure longevity. The miraculous tales depicted in these scrolls served not merely as entertainment but as vehicles for religious instruction and inspiration, making Japanese scroll paintings an essential medium for the transmission of Buddhist teachings to both literate and illiterate audiences.

The production of Japanese scroll paintings like the Inaba-do Engi Emaki was a collaborative endeavor involving multiple specialists: the narrative author, the calligrapher who wrote the text passages, the painter who created the images, and the mounter who assembled the final scroll. This collaborative nature reflects the broader cultural significance of Japanese scroll paintings as prestigious objects that required substantial resources and artistic expertise to produce, marking them as important statements of institutional authority and cultural sophistication.

Today, as we examine these medieval Japanese scroll paintings through digital reproductions and museum exhibitions, we gain insight into a visual culture that seamlessly blended the sacred and the aesthetic, the narrative and the contemplative. The Inaba-do Engi Emaki stands as a testament to the enduring power of Japanese scroll paintings to communicate across centuries, inviting modern viewers to experience the same sense of wonder that medieval audiences felt when encountering these remarkable works of art.