Throughout history, Japanese traditional patterns have captivated admirers worldwide with their delicate aesthetics and profound symbolism. “Shinko Moyōshū” (New and Old Pattern Collection), created by Haruna Shigeharu—a master ceramic artist who flourished during the Meiji and Taisho periods (1868-1926)—represents a remarkable compilation of these timeless design elements. Following our previous article on Haruna’s “Toki Zukan” (Pottery Illustrated Catalog), we now introduce another masterpiece from this prolific artist: a comprehensive collection of Japanese traditional patterns that serves as both a historical document and an invaluable resource for contemporary designers. This article explores the significance of “Shinko Moyōshū” and guides you through accessing this treasure trove via Japan’s National Diet Library Digital Collections.

“Shinko Moyōshū” – Bridging Tradition and Innovation

As its name suggests, “Shinko Moyōshū” (literally “New and Old Pattern Collection”) brings together both traditional and innovative Japanese traditional patterns. Compiled by Haruna Shigeharu during the Meiji era, this 65-page work showcases a wide variety of patterns rendered with meticulous brushwork. While Haruna’s previously featured “Toki Zukan” focused specifically on ceramic designs, “Shinko Moyōshū” encompasses a broader spectrum of patterns applicable across various art forms and crafts.

The title “Shinko” (new and old) perfectly encapsulates the transitional character of the Meiji period itself. Following the Meiji Restoration of 1868, Japan embarked on rapid Westernization while simultaneously experiencing a renaissance of interest in its own cultural identity. For Western readers unfamiliar with this pivotal moment in Japanese history, the Meiji era represented a dramatic transformation from feudal isolation to international engagement, creating a unique fusion of Eastern and Western aesthetics. “Shinko Moyōshū” stands as a product of this dynamic period—documenting traditional patterns while adapting them for a new age.

Diversity of Japanese Traditional Patterns

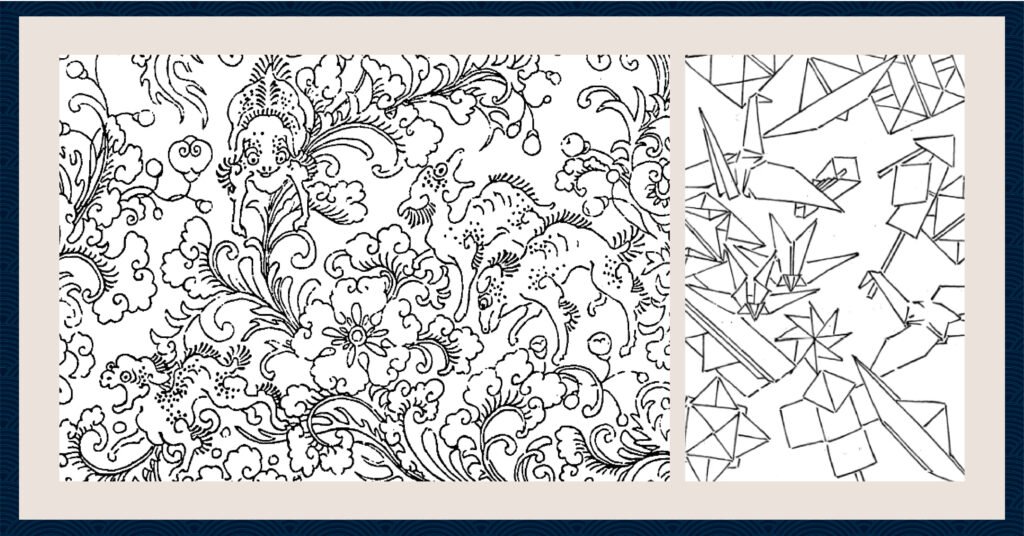

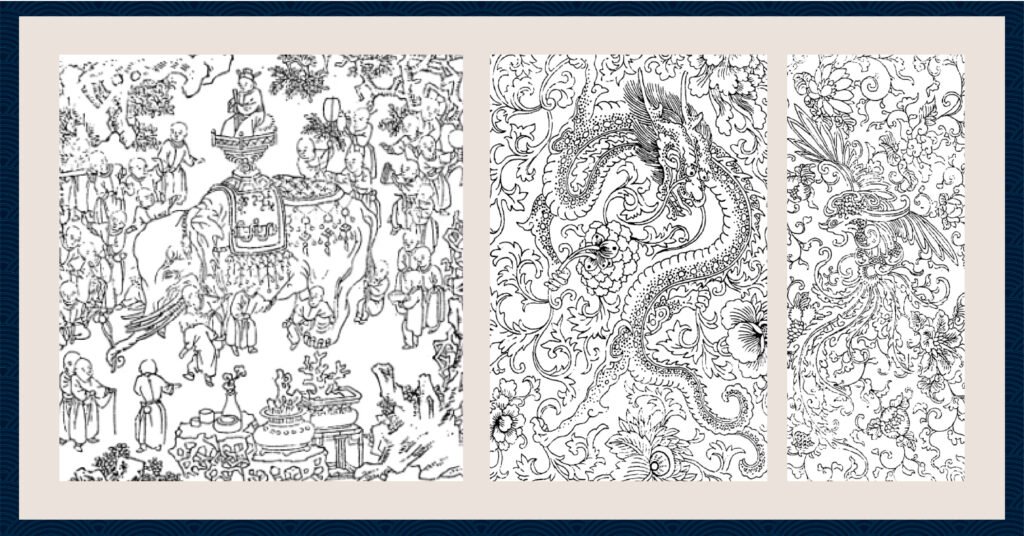

The range of Japanese traditional patterns presented in “Shinko Moyōshū” is remarkably diverse. The collection includes cloud patterns (kumo-mon), arabesque designs (karakusa-mon), chrysanthemum motifs (kiku-mon), and many other classic elements that have adorned Japanese art for centuries. The compilation also features hybrid designs that emerged during the Meiji period, reflecting the cross-cultural influences of the time.

What makes this collection particularly valuable is how patterns are presented not merely as static designs but as adaptable motifs that can be transformed for different applications. For example, some pages demonstrate how the same Japanese traditional patterns might appear differently when applied to kimono fabric versus ceramic decoration, illustrating how designs could be modified according to material and technique.

Japanese traditional patterns typically transcend pure decoration, often carrying deep symbolic meanings related to natural phenomena, seasonal references, or auspicious wishes. For those unfamiliar with Japanese symbolism, motifs like pine (matsu) represent longevity, bamboo (take) symbolizes resilience, and plum blossoms (ume) signify perseverance—together forming the auspicious “Three Friends of Winter” (shōchikubai) that frequently appear in traditional art. “Shinko Moyōshū” thus serves as a visual lexicon of these culturally rich design elements.

Historical Context of Japanese Pattern Culture

The tradition of Japanese traditional patterns dates back to the prehistoric Jōmon period (14,500-1000 BCE), when abstract decorations were applied to pottery. During the Kofun period (300-538 CE), Japanese design absorbed continental influences while maintaining distinctive characteristics. The Nara and Heian periods (710-1185) saw the development of intricate patterns influenced by Buddhist art, while the Kamakura and Muromachi periods (1185-1573) witnessed evolving styles that culminated in the bold expressions of the Momoyama and Edo periods (1573-1868).

The Edo period, in particular, saw Japanese traditional patterns flourish in popular culture through kimono designs and ukiyo-e woodblock prints. This democratization of design meant that sophisticated aesthetic principles became widely shared throughout Japanese society. Western readers might compare this to how the Arts and Crafts movement later sought to integrate art into everyday life in Europe and America.

Japanese traditional patterns reflect unique aesthetic principles that might seem contradictory to Western sensibilities. The concept of “beauty in emptiness” (yohaku no bi) values not just the decorated portions but also the empty space, creating a balanced tension between presence and absence. Similarly, the Japanese approach to stylizing and abstracting natural forms reveals a distinctive worldview that finds universal principles in particular natural phenomena—a perspective that has influenced global modernist design through figures like Frank Lloyd Wright, who was deeply inspired by Japanese aesthetics.

Haruna Shigeharu – A Master Craftsman of the Meiji Era

Born in 1847 in Kaga (present-day Ishikawa Prefecture), Haruna Shigeharu was a ceramic artist who flourished during Japan’s transition from feudalism to modernity. He studied under Tonda Kyokuzan (Tonda Tokujiro), mastering the art of ceramic painting (tōga)—a discipline that requires both artistic sensitivity and technical precision.

In 1889, Haruna’s expertise earned him recognition as a model craftsman at the Tokyo Vocational School (now Tokyo Institute of Technology), where he assisted the German scientist Gottfried Wagener in producing Asahi ware (asahi-yaki). For context, during this period, Japan strategically invited foreign experts (oyatoi gaikokujin) to help modernize various industries while retaining traditional craftsmanship—a policy that created fascinating hybrid forms in many arts.

After his work at the Tokyo Vocational School, Haruna joined the Kyoto City Ceramic Research Institute, dedicating himself to researching and developing ceramic techniques from across Japan. Beyond “Shinko Moyōshū” and “Toki Zukan,” he also created “Kachō Gashū” (Collection of Flower and Bird Paintings), demonstrating his versatility as an artist.

Haruna Shigeharu’s contributions to Japanese art extend beyond his own creations. As an educator and preserver of traditional techniques during a period of rapid change, he helped bridge Japan’s artistic heritage with emerging modern practices until his death in 1913 at the age of 67.

Contemporary Value of “Shinko Moyōshū”

Far from being merely historical artifacts, the Japanese traditional patterns documented in Haruna’s “Shinko Moyōshū” offer abundant inspiration for contemporary designers and creative professionals. For designers seeking to incorporate authentic Japanese elements into their work, this collection provides primary-source material that captures the essence of traditional Japanese aesthetics.

The patterns’ applicability spans numerous fields—graphic design, textile creation, product development, and digital arts. In recent years, as sustainability and regional identity have gained importance in global design communities, the reinterpretation of traditional patterns has experienced a renaissance. The minimalist principles inherent in many Japanese traditional patterns align perfectly with contemporary design sensibilities that value simplicity, functionality, and meaningful symbolism.

Modern digital technologies have also expanded the potential applications of these historical designs. What once adorned ceramics or textiles can now be transformed through 3D modeling, animation, or digital fabrication techniques. In this sense, the title “Shinko Moyōshū” (New and Old Pattern Collection) takes on renewed significance in our digital age—as these venerable patterns find expression through cutting-edge technologies.

For Western designers, these Japanese traditional patterns offer fresh perspective beyond the familiar Greco-Roman and European decorative traditions that have dominated Western design history. Incorporating authentic Japanese design elements—with proper understanding of their cultural context—can enrich cross-cultural creative dialogue.

How to Download the Collection

“Shinko Moyōshū” is now digitally preserved and publicly available through Japan’s National Diet Library Digital Collections (NDL Digital Library). You can access this valuable resource through the following link:

From the download panel located in the bottom right corner of the viewing interface, you can save images in either JPG or PDF format. While the link directs to the English-language interface, you can switch to Japanese by clicking the language toggle button in the upper right corner of the screen.

For those interested in Haruna Shigeharu’s work on ceramics, we recommend exploring our previous article featuring his “Toki Zukan” (Pottery Illustrated Catalog). Reading both pieces will provide a more comprehensive understanding of Meiji-era decorative arts and the remarkable breadth of Haruna’s artistic contributions.

Conclusion

Haruna Shigeharu’s “Shinko Moyōshū” stands as a precious document created by a master craftsman who sought to preserve and transmit Japan’s rich design heritage during a time of dramatic cultural transformation. The diverse array of Japanese traditional patterns contained within its 65 pages continues to resonate with our aesthetic sensibilities while providing creative inspiration for contemporary designers.

Whether you’re a designer, artist, or simply an admirer of Japanese culture, we encourage you to explore this remarkable resource now freely available through the National Diet Library Digital Collections. The opportunity to directly access such a comprehensive collection of Japanese traditional patterns offers not only a window into Japan’s artistic past but also potential pathways for creative innovation.

When we encounter works like “Shinko Moyōshū” today, we’re doing more than observing history—we’re participating in an ongoing dialogue between tradition and innovation, past and present. These Japanese traditional patterns, curated by Haruna over a century ago, invite us to discover new possibilities at the intersection of historical wisdom and contemporary expression.

Explore More Free Downloadable Resources

If you’re interested in discovering more freely downloadable historical Japanese art resources for your creative projects, click the banner below. Our curated collection includes additional ukiyo-e prints, kimono pattern books, and rare illustrated manuscripts that offer authentic glimpses into Japan’s artistic heritage. Continue your journey through the floating world and beyond with these carefully selected visual treasures from Japan’s golden age of woodblock printing.

![[Free Download] 9,000+ Japanese Traditional Artworks Now Available from Rijksmuseum](https://zenchantique.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/image-15-150x150.png)