Following our exploration of how ukiyo-e brought irezumi to life and Kuniyoshi’s revolutionary Water Margin series, we now turn to another giant of the ukiyo-e world whose contribution to Japanese traditional tattoo art deserves equal recognition. Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1864), known as one of the most prolific and successful ukiyo-e artists of the late Edo period, brought a unique theatrical sensibility to the world of irezumi art that would forever change how tattoos were perceived and portrayed in Japanese culture.

The Master of Theatrical Arts and His Journey to Irezumi

Kunisada, who later adopted the prestigious name Toyokuni III, was celebrated alongside Kuniyoshi as one of the two most talented disciples (kisoku, meaning “swift steeds”) under the tutelage of Toyokuni I. While his contemporary Kuniyoshi gained fame for his dynamic warrior prints, Kunisada dominated the world of kabuki actor portraits (yakusha-e) for nearly half a century, from 1818 until his death in 1864. His mastery extended across multiple genres—from bijin-ga (pictures of beautiful women) to shunga (erotic art)—but it was in his actor portraits that his genius truly shone.

What makes Kunisada’s contribution to Japanese traditional tattoo art particularly fascinating is the timing and context of his work. The majority of his ukiyo-e and irezumi pieces were created after he assumed the name Toyokuni II in 1843, with his most accomplished tattoo artworks emerging around 1862, when he celebrated his 77th birthday. This late-career focus on irezumi reflects not only the artistic maturity of the master but also his deep personal connection to tattoo culture.

Personal Connection to the Art of Irezumi

According to “Utagawa Retsuden” (The Utagawa Biography) by Iijima Kyoshin, Kunisada himself bore a tattoo—his deceased first wife’s name was permanently inked on his left arm. This practice, known as kishō-bori (pledge carving), was a form of memorial tattoo that served as an eternal vow of love. His first wife, the daughter of a tea house proprietor in Kayabachō, had died young, and Kunisada chose to carry her memory literally on his skin.

This personal experience with irezumi gave Kunisada an intimate understanding of tattoo culture that went beyond mere artistic observation. Known for his handsome features—unusual among ukiyo-e artists—Kunisada was the subject of numerous romantic scandals in the pleasure quarters after his wife’s death. Some speculated that his memorial tattoo served as a kind of talisman against romantic entanglements, though it seemed to have limited effectiveness given his colorful reputation.

Revolutionary Innovation: The Birth of Mitate-e

Kunisada’s most significant contribution to the intersection of ukiyo-e and irezumi was his pioneering of a new genre: yakusha mitate-e, or “actor analogue pictures.” These were not portraits of actors in actual roles they had performed, but rather imaginative casting—visualizations of what it would look like if certain actors played specific characters. As a renowned kabuki connoisseur, Kunisada was uniquely positioned to create these fantasy castings that delighted Edo period theater fans.

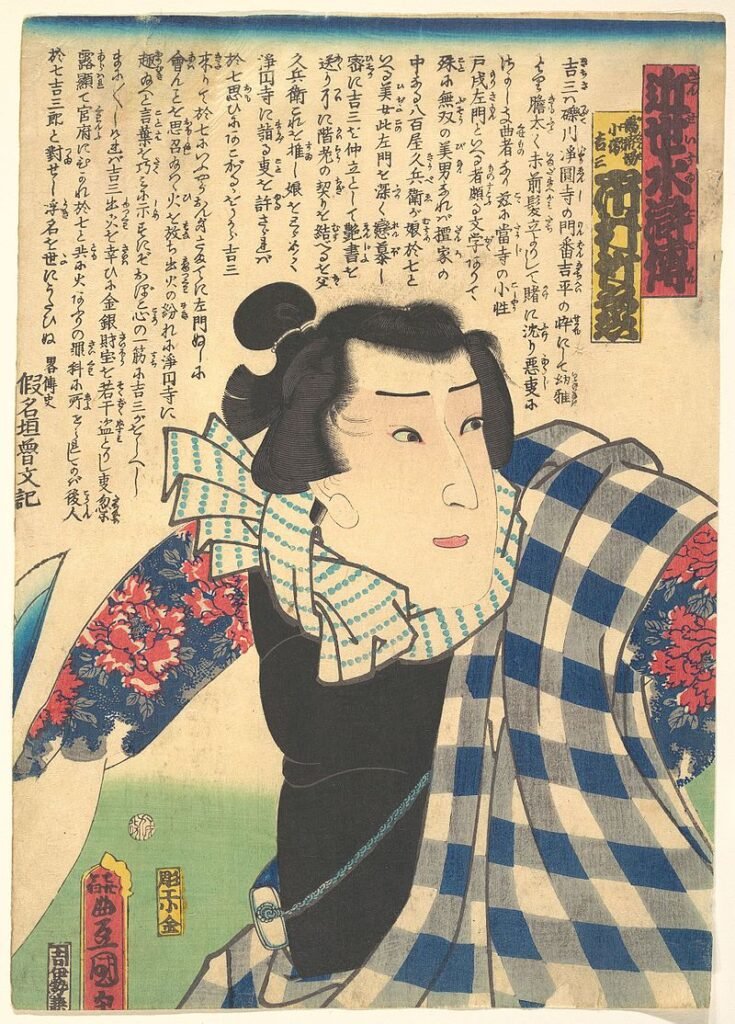

This innovative approach reached its zenith in his masterwork “Kinsei Suikoden” (Recent Water Margin), believed to be a 38-sheet series featuring characters from the Chinese classic “Water Margin” (Suikoden in Japanese). Unlike Kuniyoshi’s action-packed warrior prints, Kunisada’s approach to Japanese traditional tattoo imagery was more portrait-focused, presenting half-length images that emphasized the psychological depth and individual character of each subject.

The Artistic Evolution of Irezumi in Ukiyo-e

While Kunisada’s “Kinsei Suikoden” may have lacked the dynamic warrior aesthetics of Kuniyoshi’s work, it excelled in other aspects. Each portrait featured incredibly varied and sophisticated tattoo designs that pushed the boundaries of how irezumi could be represented in art. Kunisada took the painterly tattoo expressions established by Kuniyoshi and refined them further, creating what can be described as a more cultured, aristocratic interpretation of tattoo art—what might be called yūshoku-bi (refined beauty with historical authenticity).

Another masterpiece that showcases Kunisada’s approach to ukiyo-e and irezumi is “Tōsei Kōdanjiden” (Stories of Contemporary Heroes), a luxurious nine-sheet set arranged in three triptychs. The backgrounds feature silhouettes of pine, bamboo, and plum blossoms—auspicious symbols in Japanese culture—creating an atmosphere reminiscent of watching an elaborate courtesan’s procession. The brilliant colors and composition demonstrate how Kunisada elevated Japanese traditional tattoo art to new heights of aesthetic sophistication.

The Height of Artistic Confidence

Perhaps no work better exemplifies Kunisada’s supreme confidence in his irezumi artistry than “Toyokuni Issei Ichidai Yakura Suikoden” (Toyokuni’s Once-in-a-Lifetime Yakura Water Margin). The very title, proclaiming it as his “once-in-a-lifetime” work, suggests the extraordinary effort and artistic vision he poured into this series. Contemporary works like “Ima Shitennō Ōyama Gaeri” (The Four Heavenly Kings Return from Mount Ōyama) and “Fukaku Naka Ikiji Shin Yamato-ra” showcase the vivid beauty of irezumi art that Kunisada had perfected.

What distinguished Kunisada’s tattoo representations from those of his contemporaries was their sophisticated elegance. While maintaining the bold visual impact essential to ukiyo-e and irezumi, his designs possessed a refined sensibility that spoke to the cultured tastes of Edo’s merchant class. Through his yakusha mitate-e, the art of painted tattoos reached what many consider its pinnacle of development.

Historical Context: The Ebb and Flow of Tattoo Culture

The history of Japanese traditional tattoo art during this period was marked by government suppression and popular resistance. In 1842 (Tenpō 13), the authorities issued another prohibition against tattoos, echoing an earlier ban from 1810 (Bunka 7). This decree caused tattoo culture—whether in actual practice, theatrical representation, or artistic depiction—to vanish from Edo’s streets as suddenly as if the wind had stopped blowing. It wasn’t until the end of the Kōka period (around 1847) that irezumi culture began to resurface in public life.

This historical context explains why the majority of Kunisada’s ukiyo-e and irezumi works were produced during the approximately seventeen-year period from the late Kōka era to the first year of Genji (1864). Once the restrictions loosened, Kunisada seized the opportunity to explore Japanese traditional tattoo themes with renewed vigor, creating most of his tattoo-themed yakusha mitate-e during this cultural renaissance.

The Aesthetics of Edo Masculinity: Isami and Hari

Kabuki theater and the Yoshiwara pleasure quarters represented the twin pillars of Edo culture, serving as the wellsprings from which new trends and fashions emerged. If allure and iki (sophisticated elegance) embodied the charm of Edo women, then isami (spirited bravery) and hari (competitive pride) captured the essence of the true Edokko (child of Edo) masculinity.

These concepts of isami and hari were far more than mere bravado or showmanship. They encompassed an anti-feudal, populist sense of social justice—a commitment to living according to principles of truth, goodness, and beauty without expectation of reward. Within this philosophical framework, the spirited competitiveness of the Edo townspeople found its most powerful expression.

In Kunisada’s yakusha mitate-e, when the greatest actors of the day appeared adorned with elaborate irezumi, channeling the heroic spirits of the Water Margin heroes, they became living symbols of Edo’s indomitable spirit. These images transcended mere artistic representation to become iconographic—sacred images that embodied the ideals and aspirations of an entire culture.

The Thousand-Ryō Actors: Embodiments of the Ideal

The sen-ryō yakusha (thousand-ryō actors)—superstars like Onoe Kikugorō and Ichikawa Danjūrō—occupied a unique position in Edo society. They were more than entertainers; they were cultural icons, living embodiments of masculine ideals, and heroic figures who carried the dreams and aspirations of the common people. Their portrayals of legendary heroes on stage became templates for how Edo citizens imagined ideal behavior and bearing.

When Kunisada depicted these beloved actors wearing elaborate Japanese traditional tattoo designs, he created a powerful fusion of reality and fantasy. The irezumi, which in real life might be viewed as marks of the marginal or rebellious, became transformed through the legitimizing framework of kabuki into symbols of heroic virtue. This artistic alchemy revealed the dual nature of Edo culture—its surface adherence to order and its underlying spirit of defiance.

The Ultimate Achievement in Irezumi Art

Kunisada’s greatest contribution to the art of ukiyo-e and irezumi lay in his ability to elevate tattoos from mere body decoration to a medium for expressing character, narrative, and spiritual essence. Whether depicting dragons and tigers or cherry blossoms and peonies, each tattoo design in Kunisada’s work carried symbolic weight, revealing aspects of the wearer’s personality, fate, or inner nature.

What particularly distinguished Kunisada’s approach to Japanese traditional tattoo representation was its inherent dignity and refinement. While Kuniyoshi’s tattoo imagery pulsed with raw vitality and dynamic movement, Kunisada’s possessed a serene beauty and stylistic sophistication. This reflected his extensive experience in bijin-ga and yakusha-e, which he successfully adapted to the new expressive territory of irezumi art.

The Essence of Edo’s Esprit

Ultimately, Kunisada’s yakusha mitate-e featuring elaborate irezumi represented the “beauty of isami”—the aesthetic of spirited courage—and served as ambitious attempts to capture and express the very esprit of Edo culture. These works went beyond simply documenting tattoo designs; they sought to immortalize the spiritual essence underlying Japanese traditional tattoo culture: the Edokko’s aesthetic sensibility, rebellious spirit, and passionate embrace of life.

In the tumultuous final years of the Edo period, Kunisada’s tattoo artworks became monuments to a culture in its twilight—capturing the last brilliant flowering of a unique urban civilization. After the Meiji Restoration, as Western influences swept through Japan, irezumi would be condemned as a “barbarous custom” and driven underground. Yet Kunisada’s artistic legacy preserved for posterity a record of the sophisticated body aesthetics that Edo culture had achieved.

Conclusion

The fusion of ukiyo-e and irezumi reached its artistic apex through Kunisada’s innovative vision. His work transcended mere documentation or decoration to become art that captured the spirit of an age. In the history of Japanese art, Kunisada occupies a unique position as the artist who most successfully merged these two quintessentially Edo art forms into a unified aesthetic vision that continues to captivate viewers today.

This marks the third installment in our “Japanese Traditional Tattoo and Ukiyo-e” series. Looking ahead, we plan to explore the genealogy of tattoo artists, examining how masters like Yoshitoshi and Kunichika carried forward and transformed the traditions established by Kuniyoshi and Kunisada, creating new chapters in the ever-evolving story of Japanese traditional tattoo art.

Reference

- “Kunisada.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Accessed 2024.

- “Utagawa Kunisada” [歌川国貞]. Wikipedia (Japanese edition). Accessed 2024.

- The Utagawa Kunisada Project. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Accessed 2024.

- Genshoku Ukiyo-e Irezumi Hanga (Full-Color Ukiyo-e Tattoo Prints), edited by Fukuda Kazuhiko, Haga Shoten, 1977.1