Irezumi or horimono (Traditional Japanese Tattoos) represent far more than mere body decoration. They embody a complex cultural tradition with deep historical roots and profound symbolic significance. The distinctive style that flourished during the Edo period (1603-1868), called “wabori,” developed unparalleled artistic complexity, creating a body art tradition admired worldwide for its technical refinement and visual impact.

This art form has followed a unique evolutionary path, experiencing cycles of prominence and prohibition throughout Japanese history. This article explores the journey of irezumi from prehistoric origins to contemporary expression, revealing the cultural significance etched into Japan’s skin art tradition.

Ancient Origins and Regional Practices

Archaeological evidence suggests that tattooing in Japan dates back to the Jōmon period (approximately 14,000–300 BCE). Clay figurines (dogū) and haniwa tomb sculptures bear distinctive line patterns believed to represent tattoos worn by ancient Japanese, likely serving ceremonial purposes and indicating social status.

Regional traditions developed distinctive characteristics:

- In Japan’s southernmost islands (Amami to Ryukyu archipelagos), women practiced “Hajichi” – intricate hand tattoos from fingertips to elbows that marked marital status, commemorated womanhood, and provided spiritual protection

- Among the indigenous Ainu in northern Japan, women received tattoos around their mouths, hands, and forearms to symbolize maturity and repel evil spirits

Early Japanese chronicles like the Kojiki (712 CE) and Nihon Shoki (720 CE) mention tattooing practices among peripheral communities and as a form of punishment, indicating varying social perceptions across regions.

Disappearance and Edo Period Revival

From approximately the 7th century, mainstream Japanese aesthetics underwent a profound transformation. Influenced by Chinese culture and Confucian philosophy emphasizing bodily integrity, central Japanese regions began favoring clothing and fragrance over physical adornment. This shift marginalized tattooing, creating a historical “blank period” until the Edo era.

Following Japan’s societal stabilization after the Sengoku period, tattooing experienced a remarkable revival. The resurgence began in Edo’s pleasure quarters, where courtesans and patrons exchanged small tattoos as tokens of devotion. This practice spread to kyōkaku (chivalrous commoners) who used tattoos to symbolize personal oaths.

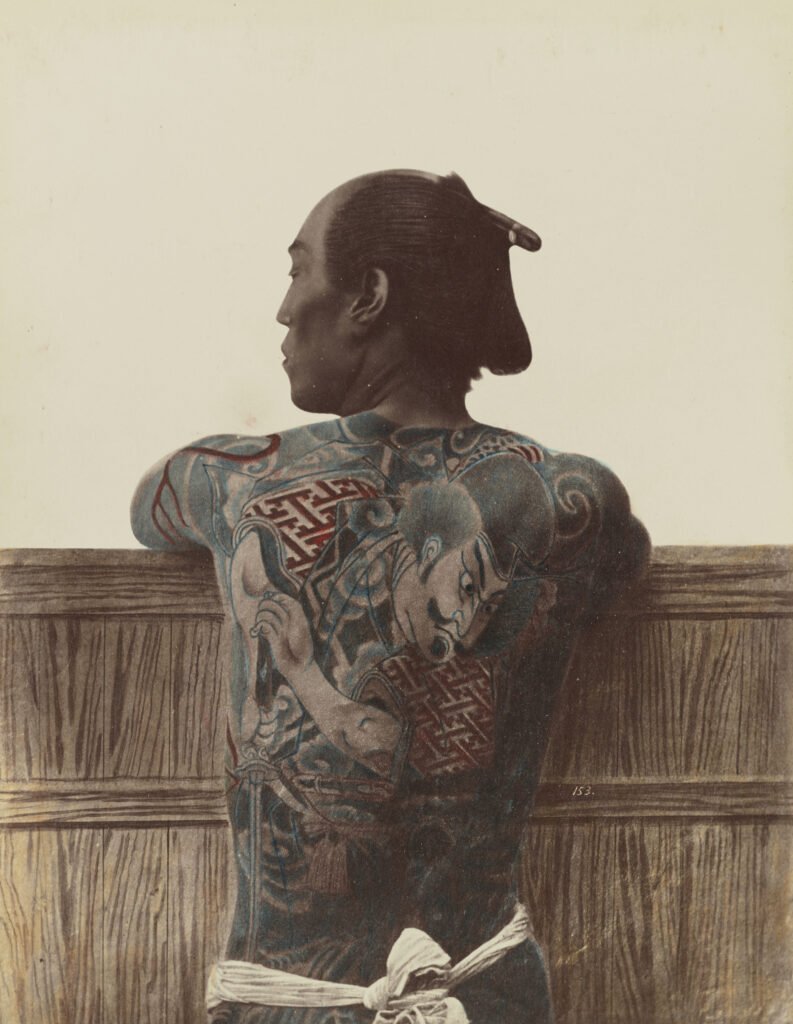

A pivotal development occurred when working-class groups, particularly tobi (construction workers and firefighters) and hikyaku (couriers), embraced extensive tattooing. Often working wearing only a loincloth (fundoshi), these laborers used tattoos as permanent “clothing” that expressed identity while covering exposed skin. Communities sometimes pooled resources to pay for young workers to receive tattoos as marks of professional pride.

Artistic Evolution and Cultural Cross-Pollination

The mid-Edo period witnessed profound cross-fertilization between tattooing and ukiyo-e woodblock printing. The watershed moment came in the early 19th century when ukiyo-e master Utagawa Kuniyoshi created his famed series depicting heroes from “Suikoden” (Water Margin) with elaborate full-body tattoos, accelerating public interest in the art form.

This artistic trend influenced kabuki theater, where productions like “Shiranami Gonin Otoko” (Five Men of the White Waves, 1862) featured actors wearing flesh-colored undergarments painted with elaborate tattoo designs. These creative exchanges drove the expansion from limited tattooing to full body compositions covering the back, shoulders, buttocks, and thighs.

The aesthetic evolution culminated in the development of the “back piece” (seppadan or munewari-soumen), establishing Japanese tattooing as a sophisticated art form with distinctive compositional principles.

Symbolism and Meaning

Japanese tattoos employ a vast library of motifs drawn from mythology, history, literature, religion, and nature. According to the 1936 document “Bunshin Hyakushi” (One Hundred Figures of Tattooing), popular subjects included:

- Heroes from “Suikoden” and legendary figures associated with success like Kintaro and Benkei

- Religious figures including Fudo Myoo, Buddhist patriarch Nichiren, and Kannon

- Animals such as dragons (wisdom and power over water), koi (perseverance), tigers, snakes, and frogs

- Botanical elements like peonies (wealth), cherry blossoms (beautiful transience of life), chrysanthemums, and maple leaves

- Ominous imagery including Hannya masks, skulls, and severed heads

Gender distinctions appeared in design preferences, with women typically choosing more delicate motifs like celestial maidens (tennin) or elegant floral compositions, while men favored warrior figures and powerful animals.

Modern Transformations: Suppression and Survival

The Meiji Restoration (1868) brought severe challenges as the new government, eager to present Japan as “civilized,” formally prohibited tattooing in 1872. This forced the practice underground and devastated regional tattoo traditions of Okinawa and the Ainu.

Ironically, as Western-style clothing became standard, concealed tattoos reinforced the aesthetic notion that “tattoos possess greater beauty when hidden” – a concept resonating with traditional Japanese values of suggestion rather than explicit display.

Contemporary Practice and Global Influence

Today’s landscape encompasses two primary streams:

- Traditional practitioners who faithfully preserve Edo-period techniques through strict master-apprentice lineages, maintaining hand-poked methods (tebori), traditional pigments, and classical design principles

- Modern artists who incorporate Western influences and technology, often combining traditional imagery with contemporary sensibilities

While Japanese tattoos continue to face social stigma domestically, with many public facilities refusing entry to tattooed individuals, internationally they are highly respected. The global tattoo community particularly admires their technical virtuosity, harmonious adaptation to body contours, sophisticated use of negative space, and masterful gradation of shading.

When Japan opened to the West in the late 19th century, visitors (including British princes who later became Kings Edward VII and George V) were captivated by Japanese tattoos. Today, the large-scale compositions, integration with body musculature, symbolic depth, and technical refinement have influenced countless artists worldwide.

In the international tattoo community, “Japanese style” or “Irezumi” represents one of the fundamental tattoo genres, with many Western artists undertaking pilgrimages to Japan to study from master practitioners.

Aesthetic Principles and Future Prospects

Japanese tattoos embody distinct aesthetic principles including:

- Harmonious relationship with the human form, working with the body’s contours to create dynamic compositions

- Bokashi (gradual shading) techniques that create depth and dimensionality

- Balancing of positive and negative space (ma) creating rhythmic compositions

- The aesthetic of concealment, where tattoos remain hidden beneath clothing, revealed only in intimate settings

Despite challenges including lingering social stigma and aging master practitioners, preservation efforts continue through documentary films, photography projects, and scholarly research. Some younger Japanese artists have committed to traditional methods despite obstacles, while international interest provides support that sustains this art form that remains controversial in its homeland.

Conclusion

Traditional Japanese tattoos represent one of Japan’s most distinctive artistic traditions—an art form carried not on canvas or paper, but on human skin. From ancient ritual markings to elaborate masterpieces, they have evolved through cycles of cultural prominence and prohibition to emerge as a globally respected art form of extraordinary refinement and symbolic depth.

The aesthetic principles embodied in these works—harmony with the body, balance of elements, appreciation of negative space, and the beauty of concealment—reflect broader Japanese cultural sensibilities that have influenced global art practices far beyond tattooing itself. Whether hidden beneath business attire in Tokyo or celebrated in international tattoo conventions, irezumi remains one of the most profound expressions of Japan’s artistic heritage—an embodied art form that continues to evolve while honoring its rich cultural traditions.

Explore more articles about Japanese Culture! Thank you! 🙂